1.6 – Longing it out

The first flurry of "feature" films (1910-1914)

I’ll be spanning a bridge in today’s entry of my “lopsided” history of film; marking the decline of the one-reeler and eyeing up the emergence of the “feature”. It has something to do with melodrama and a lick of salty sea; there’s also an undercurrent of hellishness. It’ll end with one of the longest and most expensive films made. We’ll be looking at quite a few things and in quite a lot of depth:

Fitzhammon’s English seascapes and Italy’s L’inferno (1911) 👹

The stoic realism of Victor Sjöström and Urban Gad 🧲

American “firsts” care of Chaplin and Cecil B. DeMille 🃏

The monolith that was Cabiria (1914) 📜

I know; there’s no D. W. Griffith here; but his time will come in a slightly later post, just as we’ll be giving our Scandinavian sad boys proper attention in due course.

In 1910, one-reel films were still the norm across much of the world; but their time was fast running out. In England, the Cinematograph Act—of 1909—prompted the building of the country’s first purpose-built film theatres. It’s a long way from sticky-carpet “Vue” kinoboxes, of course, but you get the idea.

Things were jilting and juddering. Electricity was in search of its ground. The “capacity”—as lanyards like to say—was making itself felt; with seats and screens now being designed for nothing but projection. In the USA, films were getting longer, bolder, more daring. Italy had caught the itch; Japan too. It wouldn't be too long before certain puritanical freaks would start declaring that there was too much film and it was showing all the “wrong” things. But that was still to come.

In Denmark and Sweden, however—a jolt in the mechanical tapestry of film—the one-reeler was about to go completely kaput; marking a sinuous sea-change in the tastes and appetites of Edwardian cinemagoers. It happened in fits and starts, with Victor Sjöström—patrician, eyes straining up, mouth pressed into unsmiling moon—going for longer and more harrowing tales of misbegotten heroines and tragic affairs of the heart. Urban Gad joined him for the ride; two quiet giants with sobering melancholia.

By the by, I’m waving my hand dismissively at the idea of defining a too-absolute criterion of the “feature” film. Sjöström’s The Gardener was 34 minutes; Gad’s The Abyss was a slightly plumper 38 minutes. It doesn’t matter! It doesn’t matter!

England wasn’t ignorant to these efforts, of course. Lewin Fitzhammon’s The Heart of a Fishergirl (1910) was “just” 8 minutes and 46 seconds long, but it pulsed with a bigger, hungrier appetite. Lulworth, roiling seas, the fragile masts of wind-whipped boats. Bodies dragged from the sea; arms flung, grasping. It’s probably not very well done, and—for much of the film—its characters sort of stand around and spam a given set of reactions like video game characters who’re stuck in a loop.1 But the ocean is beautiful; I mean this. It is savage and dangerous and the seaweed slicks and oils itself onto the cliffs like alien sputum. It was also a real film; it had a story. We are really getting somewhere; landscape was dictating the terms. But it was hardly long and very far from a “feature”.

Bigger films needed bigger budgets. They needed bums on seats. It was becoming a matter of energy and invention and—sometimes—many hundreds of extras.

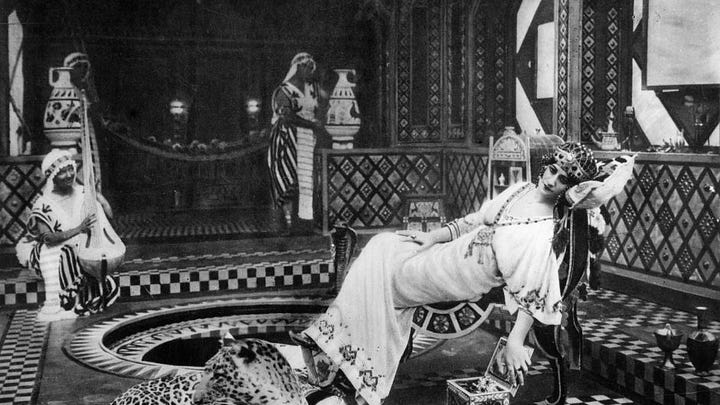

So let’s look at L’inferno—an Italian retelling of Dante’s Divine Comedy. Made in 1911, this film—a buxom 68 minutes-long—was helmed confusingly by a trio of directors: Francesco Bertolini, Adolfo Padovan, Giuseppe de Liguoro. It took them three years to make. These are the nuts and bolts.

Naturally, L’inferno isn’t the whole of Dante’s heaven-hell digression; where its producers knew—perhaps cynically—that their Italian audience would find more meat than gristle in a salacious story of hell than in a parable of paradise. For inspiration, they drew from Gustave Doré’s engravings; much as Méliès had done with his own early tricks and fantasies in France.

Like Dante, we “descend” through crepuscular layers of doomed afterlife; with each fresh scenario providing a sinister faberge’d backdrop against which Dante and Virgil pick their worried way. It is messy, mucky, crawling. It writhes like maggots in a bin.

The shots themselves—like engravings—remain largely static, but the film makes artful use of both fore- and back-ground; piling up thick strata of corporeal horrors to convey the eternal monstrousness of this hellish domain. Like Méliès—from whom the filmmakers must surely have been indebted—there are moments of double-exposure and masking used to pad out the field and introduce different scales of movement into the frame. For example, Satan’s great, final reveal; his horrible jaws chewing away on sinners like strips of beef while Dante and Virgil tremble their tiny way beneath his maw. We also get torments. Bodies scurrying across treacherous rocks; heads stuck-fast in blocks of ice; limbs sodden with flame.

L’inferno is a faithful “adaptation”. In this, it feels more like a sequence of stately and sinister dioramas than a narratively taut “story”. We’re offered precious little insight into Dante’s mood or motivation beyond snippets of cantos ripped from the literary original. Later, in 1924, Henry Otto—prodigious, prolific, forgotten—would take a more nuanced and “psychological” stab at the story; fabricating a contemporary framing narrative to connect Renaissance Italy with evil in the modern day. I don’t really prefer it.

So, while this Doré-inspired kino-diorama dangled one idea of the cinema before audiences, other filmmakers sought to shake something more “cinematic” loose. Here, we can spend a moment thinking about the sober, sorrowful realism of Victor Sjöström and Urban Gad; both of whom worked and greased and sombrely eyed-up the psychological and sociological angles of their Nordic homeland. Liberated-yet-doomed heroines, careless cads, bitter love triangles ending in desperation and death. Asta Nielsen—we’ll get to her in a later post—worked these emotions with a newfound subtleness that would prove enormously influential.

Despite their high-strung storylines, these films—the first cinematic “dark wave”—give off a more sober naturalism than was then popular in the rest of Europe and the USA. They were patient, doom-laden affairs slaked with Lo-Fi torments and existential pity. Their heroes were ordinary and struggling and real—their plots end often tragically. The Gardener, The Abyss, and The Black Dream all seeped out a sombre maturity that proves that film had grown up. Expressive light, downcast gazes. Here were the primeval precursors that Bergman—many years later—would heat into his own erotic-myopic miasma. Sjöström would even act for him.2 Film has always returned to itself.

Elsewhere. “Firsts” were cropping up all over the shop. We get the first feature-length comedic outing with Tillie’s Punctured Romance (1914), while Cecil B. DeMille sprung into 1914 all-guns-blazing; pummelling out six features in the space of a year.

First, Tillie’s Punctured Romance—a Mack Sennett production; care of the Keystone Company—saw Chaplin briefly ditch the “Tramp” character he’d bow-leggedly debuted in short-film-form in favour of playing an unscrupulous playboy and bounder. In fact, the entire cast was a scrabbly, sensational hoot; and the film has the added allure of being wildly successful as well as featuring one of the very first “films within a film”.

There are things to expect here; formally. Characters “step out”—are introduced—during the pre-film credit sequence; effectively bowing to the unseen “audience”. You can read Marie Dressler’s lips; she clasps her hands together and, looking slightly beyond and above the top left of the camera, says “thank you”. Costume change—cross-fade—and we get another cross-fade from a curtained hall into a garden. The film has “begun”; Dressler’s eyes bulge open—what the hell am I doing here? It’s funny-silly already; the film has barely begun.

It’s not quite slapstick; more like a comedy of manners and circumstance with a lot of kicks and punches thrown in. Most notable—perhaps—is Sennett’s approach to landscape photography; and the scene where uncle Banks falls from the mountainside is delivered with positively Nordic sobriety. Look how beautifully composed this sequence is!

For DeMille, meanwhile, The Squaw Man (1914) had the auratic novelty of being Hollywood’s first feature production; a continent-sprawling tale of deception, attraction, murder, retribution. Here, we get a first taste of the role that the frontier would play in the American cinematic imagination; where much of the film’s action takes place in Wyoming. It was also a Western—chaps, six-shooters, bar-brawls, &Etc. DeMille—who’d remake this film three times in his life—gave early shape in The Squaw Man to the gunslingers, gangsters, and fallen women—all those heavy-shouldered “types”—who would define the cinema of the 1920s. This was still to come.

The film itself. Busy medium shots in packed parlours and race-track stands livened-up with the odd insert and thrown-open landscape; lending it a kind of melange-like quality. The story itself is hysterical and slippery; little helped by its slew of baffling intertitles and jump-jolts in the narrative that are so harebrained it’s basically impossible to follow.

For example, the honestly baffling scene-change to the Alps; whereupon Henry, after slipping off a small rock the size of a large rock, has enough wherewithal to make a death-bed confession that old Jim is innocent; cue everyone reappearing in Wyoming again and sort of wrapping things up, even if Nat-u-Ritch (Lilian St. Cyr) dies in the process. The burning ship, the steam boat, the bar brawl, the pickpocketing, the Derby day, the local sheriff’s re-election bid. It has a too-muchness that stews into a kind of bananas-everything.

That being said, the snowy mountain scenes are lovely to behold (like Tillie’s Punctured Romance imo)—just as the inserts are deftly handled and really do nudge the narrative forward; filling in the (many) blanks that otherwise pepper the film.

It’s easy to forget that this was DeMille’s first film, Lasky’s first production; that they were running on a shoe-string budget in an undeveloped part of the San Fernando valley—and that DeMille’s movie orientation to date had involved an afternoon spent at the Edison lot. Later, in The Cheat (1915), DeMille would take this plot—embezzlement and the social and emotional torrents that fall out from it—and render it down into a more chewable and satisfying form; as well giving us a brilliantly malevolent turn from Sessue Hayakawa. You deserve to hear about this in more detail; and you will.

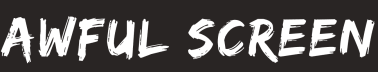

In Italy, meanwhile, a new largeness heaved into view. In 1913 and 1914 respectively, two massively influential films—Quo Vadis and Cabiria—would express that uniquely Italian obsession with monumentalism, history, spectacle. Both films strip-mined the ancient Roman past for their narrative meat, but it was Cabiria—filmed by Giovani Pastrone, with his comically alert moustache and piercing eyes—that would send the deepest reverberations through cinema. D. W. Griffith learnt much from it that he would judiciously apply to his own gigantic experiments in the USA; as did DeMille. Here was film as a powerful instrument for narrative storytelling. Roger Ebert was fulsome with his praise: “Pastrone helped free movies from a static gaze”. Martin Scorsese, another fan. It was the first “epic”; a paving stone on the road to Wyler’s Ben Hur (1959) and a distant relative of Federico Fellini’s Nights of Cabiria (1957). Everyone owes it something.

Really, Cabiria is two stories—one large and historic, the other intimate and relatable. The eponymous “Cabiria” is the daughter of a wealthy Roman who, through a series of largely inexplicable events and accidents, gets sold into slavery; the “best” part of which is the spectacular eruption of Etna; providing the narrative device which sets Cabiria’s story in motion. Masonry tumbles, steam hisses, sparks fly. There are many waving, gesturing, freaking-out bodies whose sole intent is to provide a sense of scale and largeness. Meanwhile, Fulvio and Maciste—two Roman spies who’ve gone to ground in Carthage—variously attempt to upset the proceedings while searching vainly for the long-forgotten Cabiria. It’s probably accurate to say that their antics provide one of the earliest examples of the “buddy movie”. Fulvio is sly and small, Maciste large and loyal. Pastrone cross-cuts his narrative; he builds these pieces—often confusingly—side by side.

Much happens in Pastrone’s mad masterwork, including a handful of dazzling set-pieces whose scale and inventiveness would only be bested by D. W. Griffith. But I’m also minded to celebrate Cabiria’s subtler arts, like how he used rails to dolly his camera around the set; pushing toward and away from the action like a gently floating feather. This device heralded a new ubiquity of image in the cinema; demonstrating that the camera needn’t remain fixed on its pedestal but could play a shapely role in unfolding the film through its pirouetting movements. In Bodastoret’s tavern, Pastrone dollies his camera across the span of the room; slowly “revealing” and then tracking the action as it unfolds. He does this through lover’s trysts, chases in gardens, scenes of war, acts of celebration. When we first meet Cabiria in her father’s sprawling villa, the camera dollies toward the action; picking out Batto—her gregarious father—and pushing away those details that are not relevant. It draws us toward these characters, telling us who we should give our attention to. This man matters; this character is important. Pay attention. In this figuration, the camera is a glacial and flowing “eye”. It reinforces the idea that what we are watching isn’t a “film set” but the living texture of history. It feels obvious and natural. Pastrone got there first.

In the film, he also made use of close-ups and depth of field; using space and “volume” to lug his story along. I love the scene where Fulvio steals back into the city of Carthage; climbing up a pyramid of bodies. It is shot mostly in silhouette, the wall and the “stack” of bodies filling up the left hand-side of the frame; Fulvio must make his way to the right—up and over the wall. This thing is tense. Later, how the two Romans hide from their pursuers in a culvert of hidden foreground while their enemies charge and stomp across the upper ceiling of the frame. There’s a moment where one of Etna’s survivors briefly contemplates Cabiria’s family ring; Pastrone shows it to us in a rich, soft close-up. Taken together, it is like a fresco—part Fra Urbino, another Raphael; tiny figures measuring only as grains of wobbling dust become an integral part of the action. They are its emotional sedimentation.

But for all its massiveness, Cabiria’s “heart” is the affable, affective relationship between Fulvio and Maciste; making it a much fresher and gladder film than other more sober works that would be inspired by it.3 Really, Pastrone understood that epic stories—at least in popular entertainment—ask for a more humanising edge. Ebert again is so moving and good on this film: “These people are all dead, but here they are as they were on that day in 1914, boldly telling a story in a new medium”. It is a living, palpable, corporeal thing. The “new bigness” was coming; and it would shake almost everything up.

Film’s first forays beyond the one-reeler set a lot of things in motion. Everything was happening very, very quickly. The old-hat and hackneyed way of doing things—painted backdrops, immobile cameras, OTT “expressive” acting—began to lose out to vertiginous and increasingly durational experiments.

There’s much I’ve had to skirt or avoid: like Stellan Rye’s The Student of Prague (1913) and Louis Feuillade’s archly decadent, conspiratorially thrilling Fantômas serialization (1913), whose top hats, tailcoats, cat burglars, and calling cards gave audiences an “immense” and “explosive genius” whose English-language ads—sold to international film exhibitors—promised that there would “always have a full house” when its reels were set flying. I would have been there.

For old-heads like Edwin S. Porter, however, the adjustment was almost too much to bear. His Tess of the Storm Country—a five-reel drama from 1914—left Mary Pickford picking the bones out of Porter’s soup; criticizing his stuck-in-the-mud filmmaking that hadn’t much evolved since 1903. In fact, she claimed that he “knew nothing about directing. Nothing”. Maybe that’s unfair; maybe not. But it just goes to show how fastly faceted film was becoming on the cusp of the Great War.4

Adieu, one-reel cinema! But it wasn’t really “gone”. Shorter films would muscle their way back through the cinematic froth. There would be tiny experimental musings and primeval avant-gardes and any number of crankily cool things that started shooting back into the rump of film once the Big Boys—the studios, the producers—had exhausted themselves with going large.

This period—our loose-edged early 1910s—was one where film was putting its armour on and riding out to battle. It was engorging itself; and the films were only going to get bigger and more spectacular. But as film established a “convention”—not just a “language”—it would fall prey to increasingly weird experimenters who’d pull the stuffing out of its sofa and push the proverbial cups off its tables. Man Ray, Buñuel, Léger, Duchamp, René Clair would all—in a long decade’s time—reinvent film all over again. The 1920s were a long way away yet; but not too far.

But in order for the un-making reverse-rewinding of film to happen, it needed to get increasingly bigger. Make yourself—and then pull yourself apart. The death of the one-reeler was a necessary violence.

But let’s be fair; Hay Plumb (Jack) and Claire Pridelle (Nancy) had been “discovered” by Cecil Hepworth at Walton Regatta. They were sufficiently game to accompany him to Lulworth Cove; where they would make a batch of films—of which Fishergirl is but one.

In fact, my first exposure to Sjöström was his role in Bergman’s Wild Strawberries (1957)—playing the softly rueful, gruff and professorial Isak Borg. It’s a film I love very dearly.

Maciste proved such an appealing character that Bartolomeo Pagano would reprise the role some fourteen additional times between 1916 and 1926; heralding him as one of Italy’s earliest “stars”. These later films would bring Maciste from the past and into the present day, turning this great wall of a man into a kind of “lens” that would peer back onto Italy itself. He would appear in the afterlife, at the Olympic games, as a solider.

Pickford was right, to be fair; the film feels flat and old-fashioned when compared with the visual verbosity that DeMille, Sjöström, Gad, and Rye were contemporaneously getting up to.