1.5 – Throwing punches

How two flicks from 1897 predicted the future of film

You cover a lot of ground very quickly when you write a history; tumbling ahead and missing all sorts of things along the way. It’s an aleatory affair; more like a hodge-podge than a systematic retrieval. That’s why I’m going to spend some time, in this entry, not only going back—to 1897—but looking at two films in a bit more detail; eyeballing the particulars, and hopefully using those particulars to say something wider about film at the turn of the last century: what was it, and where was it going?

In this post, I’ll be covering:

Fructuós Gelabert and Spain’s first narrative 🇪🇸

How Enoch J. Rector shot a prizefight — and caused a sensation 🥊

Foreshadowing how film would become wrapped up with morality 👮♂️

What was brand-spanking-new for Spain had already been around the block in France and the USA, where the first Iberian film came in 1897; taking its slow-damned time to cross the French-Spanish border. That’s how the oft-repeated story goes, at least; and it’s entirely possible—probably probable, in fact—that other contenders came earlier. We know that the Lumière brothers brought their travelling film programme to Barcelona—trains arriving, workers leaving—in May 1895. Must have felt good to be somewhere warm, for a change.

But it fell to Fructuós Gelabert—a native son of Barcelona, prodigiously round of frame and spectacles alike—to produce Spain’s first proper narrative. In boisterous fashion, he chose to depict a fight. The resulting film, Rina en un café, is thirty seconds long. It is a fight, which is a fact that is not obvious from its title.

That same year, America was also thinking boisterously; albeit on a much grander scale.

Enoch J. Rector has the kind of biography that feels so very typical of the late 19th American century. Boxing promoter, inventor, partner in the Kinetoscope Exhibition Company. He was a narrow, willowy man with a crisp moustache and parted hair—and he had an easy flair for spotting opportunities.

In 1897, the opportunity that came to him was the Corbett-Fitzsimmons bout; a much-anticipated fight that took place in Carson City, Nevada on March 17. It was a prizefight, a lot of money and prestige was riding on it. The hype is typically American, and the resulting film—which was subsequently toured around the country, from Boston to Tucson—has attracted such high-flung claims as, “it was boxing that created the cinema” (so says Luke McKernan).

Perhaps. The fight film—100-minutes long, screened nationwide, a kind of early sport-media-film sensation that wasn’t just widely seen, but alluringly profitable—might be considered closer to a pay-per-view TV broadcast than a film-film. In this light, boxing didn’t create the cinema; it created the box office.

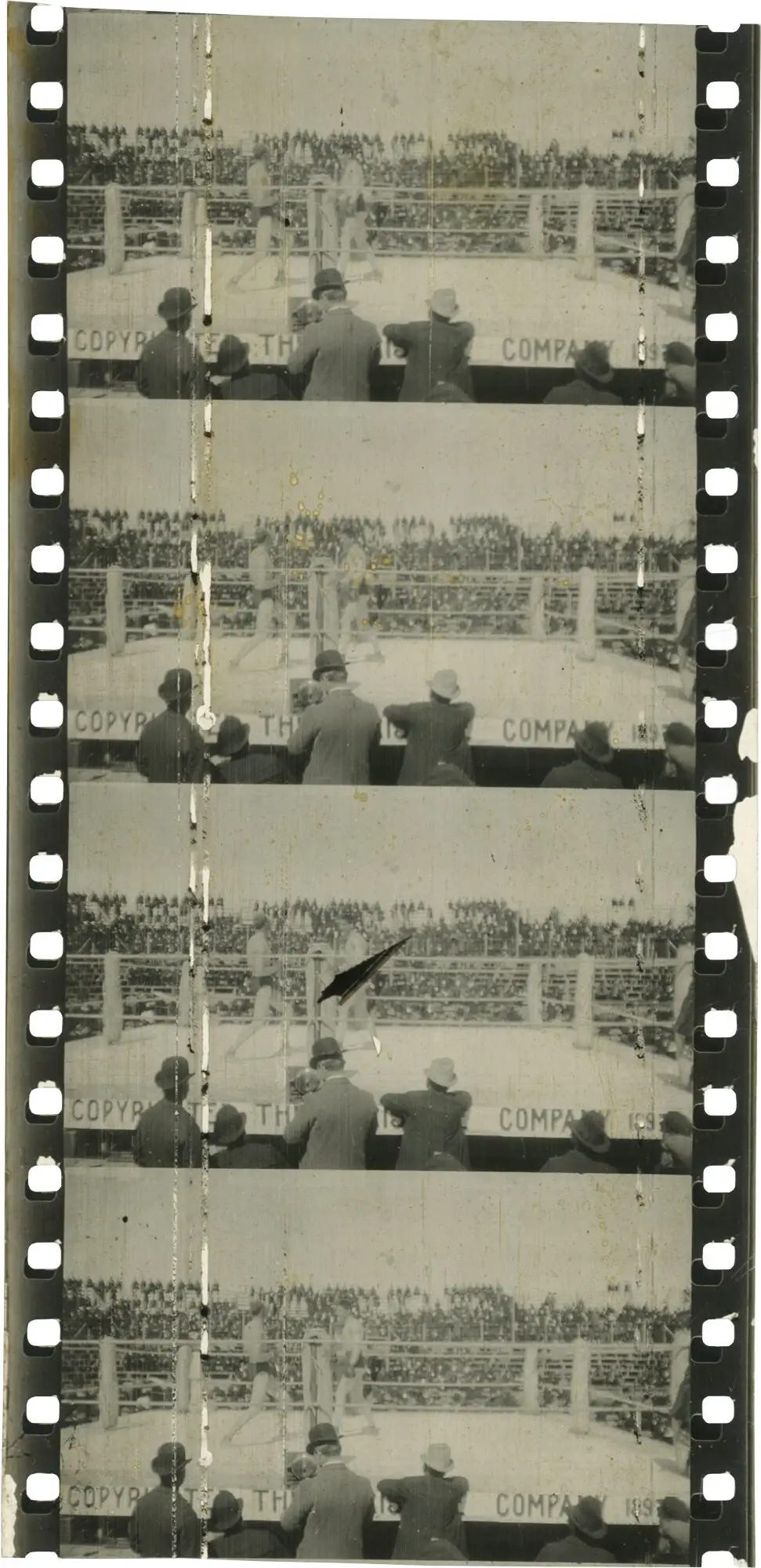

But, in 1897, 100-minutes was a damned long time. Rector had to overcome some needling hurdles to make it work in its wide-screen format—and at such great length; making use of a technology called the Latham Loop. Three cameras placed alongside each other, each running 63mm nitrate film; aspect ratio of 1.65:1. It was as wide as it was long. Figuratively speaking. It meant that Rector and his crew could also load and expose the film in a basically continuous fashion. It was less an act of delicate artistry than a three gun salute fired into the aether of the American imagination.

Not all of the film survives today; just nineteen minutes or so, transferred from a print owned by New Yorker Jean A. LeRoy that had been dug up in the 1980s.

It had an introduction, it had the fight—the meat of the film—and it even had a kind of postscript; where we see the empty ring and the audience members who eventually scramble into it. It lollops and swims; this very wide frame with two pale bodies in short shorts making feints and jabs and leaning away from each other. Less concussive than liquid. Bowler-hatted gentlemen, seen from behind, arms folded gazing into the ring (promoters, coaches, gamblers—who can say). I even think there’s some kind of advert facing us along the lip of the ring.

It might have made $750,000. It very easily could have made less; but that’s for the proper historians to figure out. Might be worth noting that the film courted some controversy too; at the time, women were barred from attending fights—but they weren’t banned from watching one on film. Here was a loophole; a first or early instance of film slipping the bounds of the “real” and ruffling feathers as it did so. Frames within frames, Corbett had earlier acted on the stage in a fictionalized version of himself; the Women’s Christian Temperance Union were aghast; an editorial in The New York Times cocked a snook at it (because this great new technology had been bent to such ‘ordinary’ and violent ends).

In short, the 1897 fight—or its filming—signalled some of the perturbances that would later clatter and crash down on American movie morality through the auspices of Will H. Hayes. This was the edge of a moral minefield. But 1934 was a long way off yet.1

It was also the cause of some litigation, when Siegmund Lubin—film’s first great “pirate”, who deserves his own entry in this history and will probably get one— restaged a dramatisation of the fight on a Pennsylvania rooftop and shot the whole thing on film. I’ve seen it said that the fight film dragged the movies into the “low brow” (Terry Ramsaye). It was a filmed fight that was most capable of starting fights.

If Rector’s fight was proto-Blockbuster TV entertainment, then Gelabert’s film was conceived as something more akin to the early Lumière narratives; where a group of men hanging around a cafe end up brawling over a woman. It’s also wide; giving us the cafe tables—it’s outside, Spain in the summer—and a patch of public square, a flight of stairs, trees; everyone decked out in suits, though it becomes quite hard to distinguish their faces.

The version I’ve seen opens with a medium shot of Gelabert—who smiles, cane in hand, sitting down; I suppose this was by way of an introduction, almost like a theatre director taking a bow before their audience. There’s something charming about it; still sort of sense-struck by the idea of what film is and what it can “do” —a kind of quizzical sensation that everyone is just glad to be enjoying, like a magic trick when the illusionist winkingly lets the audience in on their gambit.2

In its tiny totality, Rina en un café has—as Zuriñe Piña Landaburu observes—everything that the cinema would ultimately contain: love, jealousy, violence, as if it was a teeny-tiny shot-glass-sized reduction of the currents that were about to pulse through the narrative cinema. It even has a happy ending.

Two films, two fights, two continents. In 1897, we can see different imaginaries of the cinema raising their heads: one that had its eyeballs on dramatic fictions, the other on the long-played possibilities of time and duration. It also becomes abundantly clear how quickly film was shaking itself loose; with any number of inventors rushing to lever and crowbar the “cinema” into as many shapes as they could come up with. Even in its relatively simple form, Gelabert’s work knew that film turned on the fulcrum of a story—just as Rector knew that audiences would become increasingly hungry for longer flicks, and that both were capable of causing their own kind of sensation.

Gelabert would eventually go on to experiment with documentaries and historical dramas, the latter—like Guzmán el Bueno (1910)—made use of three-dimensional sets. Later, seemingly in the 1940s and ‘50s, he created early concepts for 3D filmmaking. Rector, meanwhile, would seem to disappear from film; at least according to those records that I was able to find. His obituary has him working in Bolivia, Buenos Aires, Texas—an oilman. Perhaps he had already made his fortune. Gelabert struggled financially for much of his life.

If there was a great deal of money to be made in cinema, it was not distributed evenly. Many people seemed to drift away, fall away, dissolve—the “contrary” and “shifting imperatives” of the early cinema (Stephen Barber), being so malleable and prone to dissolution; even if its story is one of ratcheting and intensification. History is written by the victors, &Etc.

Both Spain and America would come to play increasingly large roles in film—but the types of stories they’d tell would continue to bifurcate down very different trajectories. Hollywood would give us Billy Wilder and Cecil B. DeMille; Spain, Victor Erice and Luis Buñuel. I might be comparing apples and quinces, but isn’t that the point of a global history?

I’m talking of course about the institution of the censorious, morally uptight Hayes Code, which imposed a bevvy of strict rules and guidelines on movie producers between 1934 and 1968. No nudity, not even the suggestion of it; no drugs; no “detailed” crimes. In short, no fun.

It should be noted that Gelabert had the sole surviving copy of Rina en un café, and he created a distribution version of the film much later—in 1952. I’m minded to believe that the shot of him was a later insert rather than an original component of the film, but that’s for the birds.

Owen, you have to give us your Letterboxd account! Also, I think you'd get along with @Pete Cavill