1.3 – Extremity

How the close-up changed cinema (1900-1911)

This is part 1.3 of my “lopsided” history of film. Today, we’re going to spend no small amount of time looking at looking; specifically, at how some of the earliest filmmakers—amateurs as well as now harder-nosed types who’d been around the block—began to experiment with “close-ups”, which I’ll scare quote just the once. You already know what they are. Roundly, I’ll be looking at:

G. A. Smith’s first experiments with telescopic shots 🔭

How James Williamson ate his way into film history 👄

D. W. Griffiths’ uncanny attention to detail 🔧

The first month of writing this history has me feeling a deep well of respect for actual historians, and there is always the gnawing doubt that I might have missed something or somebody really important. But I can’t watch and read everything; even if I feel like I should. By the way, is there something I’ve overlooked—or a fact I’ve disfigured? Drop me a DM or a comment. I will read it.

“Mr Smith believes himself to have the power of vivid visualisation”

— Eleanor Sidgwick

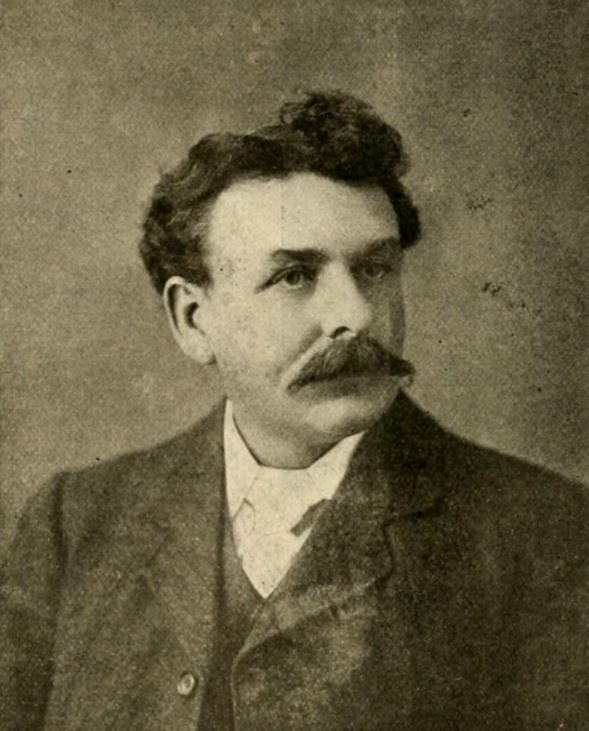

G. A. Smith—a bushy-haired raconteur hailing from London’s Cripplegate—made a name for himself as a stage hypnotist before he turned his attention to the world of film.

But magic’s loss was cinema’s gain, because George Albert Smith would play no small part in helping film unbutton itself from the stagey-fixedness of the theatre and become something that we now recognise as big-F film.

There’s a pattern here, I think, in how closely magic and the cinema were interwoven through the 1890s and early 1900s, when so many conjurers and illusionists—some of whom were certainly shysters and opportunists—threw their lot in with film. In fact, it’s something you might recognise from earlier entries in this history. How’s that for a clever backlink?

For G. A. Smith, however, his act—performed at the Brighton Aquarium (which is either the worst or best possible place to practice illusions)—involved a blindfolded performer identifying unseen objects selected by the audience, as well as the psychic “transference” of unseen numbers. It was a matter of some contemporary speculation as to whether Smith’s act was “genuine”, and to what extent he was hoodwinking his audience. Take your pick.

Ever the man about town, Smith supplemented his income by cultivating a pleasure garden in his adoptive home of Hove; where he staged public exhibitions that ran the gamut from hot air balloons to lantern shows. Later, he would construct a film studio in its grounds. In this way, you might think of him as the English Méliès.1

In 1889, Smith co-authored Experiments in Thought Transference with Henry and Eleanor Sidgwick, about whom I know nothing beyond their names. The paper—which is dense and cautious, and I don’t really know why I read it—reports an experiment convened between Smith and a “Mr. W”; a “clerk in a shop, aged probably about twenty-one or twenty-two”. Having hypnotised his subject, Smith believed that he could “transfer” the image of a randomly selected number between his mind and “W”s. Their dialogue is reported, in part, as follows:

Smith: Do you see this?

W.: Where? [pause] I see him now — a “3”.

Smith: Yes. Do you see any more?”

W.: No.

Then, after a lot of ambivalent back and forth—during which time Mr. W fell into a deeper and perhaps predictable state of sleep—the subject “suddenly awoke himself”. There was no further opportunity, on that day, to pursue the experiment.

Eleanor Sidgwick observed, dryly, that “Mr Smith believes himself to have the power of vivid visualisation”.

It would turn out to be a strangely prescient remark.

There was nothing particularly spectacular about film’s first close-up. It took the shape of a game old lark that camouflaged a great deal of its revolutionary potential—as would be the case for so many early films at a time when stories were kept light and bright for their half-distracted spectators. Filmmakers were trying things out; their audiences were sufficiently entertained to indulge them. It was an arrangement that seemed to work both ways.

This film—Grandma’s Reading Glass—was produced by G. A. Smith in 1900. It features a not-so-old “grandma” and her (presumed) grandson who idle away the time by using the eponymous reading glass to inspect a Bovril advert, a pocket watch mechanism, a canary in a cage, the old lady’s beady eye, and—eventually—a purring kitten. The camera become a surrogate for the subject and viewer’s eye—a circle of film masked off against black.

For Grandma’, there’s no narrative structure to speak of; making it “little” more than a technical demonstration (albeit a kindly and heart-warming one). It’s a “trick” film. It cuts between a pair of medium shots and a point-of-view. But, in these seemingly unremarkable movements, “he helped to teach his contemporaries how to create a filmed sequence”. The cinema started small.

Later that year, Smith repeated the trick with a bit more thought put into its structure. As Seen Through a Telescope is a three-act flick whose story goes something like this: frock-coated professorial type pulls a telescope from his pocket, extends the mechanism, and takes a look around. He’s all attentiveness and curiosity. Now the inventive bit: we see what the rheumy old man is actually looking at through his lens; namely, a woman’s exposed calf and shoe, which a pair of hands—not her own—are fussily lacing up. G. A. Smith lets us have a good ogle before cutting back to the wide-angled street scene, whereupon our professor congratulates himself, takes a seat, and is subsequently knocked over by the irate lace-tying husband.

It’s all over in about 59 seconds.

Harmless eye-lolling kiss-me-quick seaside stuff, for sure; but Smith’s circular close-up was a big day for the fledgling cinema.

Like its sister film, Telescope is an instance where the subject—a reading glass, a telescope—is a device that is already understood as a collapser-of-distances. You can follow Smith’s thinking; how film isn’t just an even-keeled documentation of “something-happening”, but a slithering of tendrils that attach parts of bodies, parts of speech, parts of parts. We can “ride” the lens with our own eye. We can rattle around inside an actor’s head and see what they see—and look at the things they’re looking at.

In these two films, Smith was building out the rudiments of a “grammar” of film; adding flesh to its bones and flaying off the parts that belonged to stages and paperbacks. It was heady and intoxicating stuff; so much so that Smith’s industrious confabulations would have Charles Urban “yelling like a cowboy”. He also did some really puffy, pretty things with soft focus and narrative editing.

This is presumably why the BFI included Telescope in their “primitives and pioneers” collection. I mention this mostly because the title alliterates nicely, but also because it lands on a smudgy truth about Smith; that his scrappy-curiosity-craftiness would turn out to be foundational to the cinema. He really was breaking new ground; one act of public perversion at a time.

It would fall to James Williamson, a Fife-born chemist and seller of photographic chemicals and equipment, to pick things up where Smith left off. If Smith was Méliès, Williamson was his Lumière—even if both of their names are often excluded from those grandiose, sweeping-style accounts of early film; though Mark Cousins at least gives Smith passing dues in his The Story of Film. Williamson gets a glance, too; but it isn’t held for long.

In 1901, Williamson directed The Big Swallow—a short trick film which is defiantly simple in its execution but fashions and configures the close-up into something much more radical.2 He built on Smith’s work; taking the idea further.

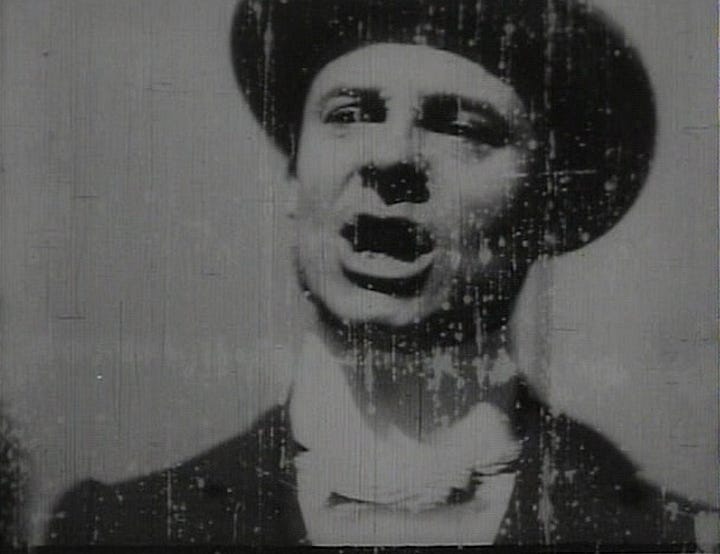

Here, we see a man—played by Sam Dalton, a professional comedian—in medium shot; his eyes flashing and winking down the lens, gazing directly at us. “I won’t, I won’t!”, the intertitles declare; “I’ll eat the camera first”, before proceeding to approach the camera—and us—until his mouth opens and appears the swallow the camera, cutting to a shot in which the filmmaker and his equipment tumble into the hungry maw. Having gorged on his peculiar meal, he retreats.

For Michael Brooke, Williamson was probably having a bit of a fun with his own experience of dealing with “unwanted attention from increasingly savvy passers-by while filming his actuality shorts”. I don’t know if you’ve seen any of those early actuality street scenes; people can’t help but stop and gawp and gather around the camera. I guess Williamson wanted them to act more naturally, or feared that they might eat him.

Unlike Smith’s experiments, The Big Swallow has a peculiarly destabilising effect; messing around with the audience’s sense of perception in such a way that it would become of great interest to the Surrealists. Perhaps a little Un Chien Andalou, avant la lettre.

Fred Talbot, in his Moving Pictures: how they are made and worked (1912), goes into some detail about how Williamson pulled the shot off; having attached the racking bellows of an “ordinary” camera to his cinematograph and using this instrument to refocus the shot as Dalton approached the device; where Williamson had chalked out his points of focus on the ground, adjusting as the “swallower” approached:

“Presently only his head was recorded; then nothing but the open mouth and teeth; and at last, when he almost touched the lens, nothing but a black cavity was revealed upon the film.”

The whole thing was assembled through a careful kind of stop-motion; interlinking Dalton’s walking approach, the “swallow”, and his now satisfied retreat. It is wily and strange and funny in the manner of G. A. Smith’s own Old Man Drinking a Glass of Beer from 1897, where Smith had first kidded around with the idea that the camera didn’t need to be yards and yards away from the performer. Instead, we’re close; we see the bottle, the old man’s upper half, his increasingly lively hands, his gurning face.

Really, it took an amateur—or a pair of them—without any kind of stage background to realise that film didn’t have to involve just “plunk[ing] down their camera at a likely distance and let[ting] it grind”, as Fritzi Kramer puts it. Smith and Williamson showed us what film—as its own very new and different media—could become. Not “filmed theatre”, but something to do with perspective, time, vision, composition—and the derangement of all these things. Even then, these close-ups promised the suturing-together of a language that would, for Serge Daney, become “the same language”; shared by acolytes who might otherwise not share the same mother tongue.

They were the first collective utterances whose syllables started with a reading glass, a telescope, a watch. These are mechanical intimations of proximity, collapsed distances, the folding of time; all of which would eventually become Daney’s language. In fact, all of our language. We speak it so fluently that skips our mouths and plants itself directly in our eyes.

If these English films hinged on the close-up—they were demonstrations as much as entertainments—then what of those films in which the close-up played a part, but wasn’t the “whole” affair?

By 1911, D. W. Griffith—who we all know for being as difficult and controversial as he was creatively brilliant—had already spent some time larking around as a stage extra in a handful of American Mutoscope and Biograph Company films before going on to direct a not insignificant number of productions for them; including the first ever film shot in Hollywood, California. He had a habit of being ahead of things.

Before falling out with Biograph—he would go on to found his own Mutual Film Corporation, where he’d be free to overrun and lose as much money as he wanted—Griffith shot a curious 17-minute film that demonstrated his canny familiarity with Smith and Williamson’s experiments across the pond.

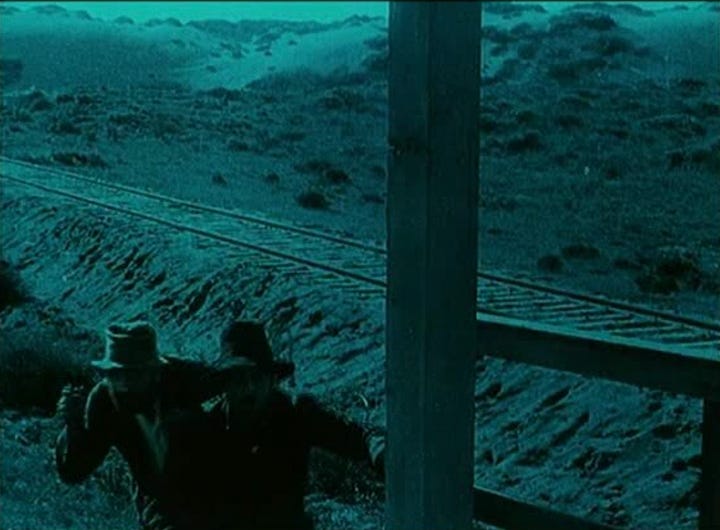

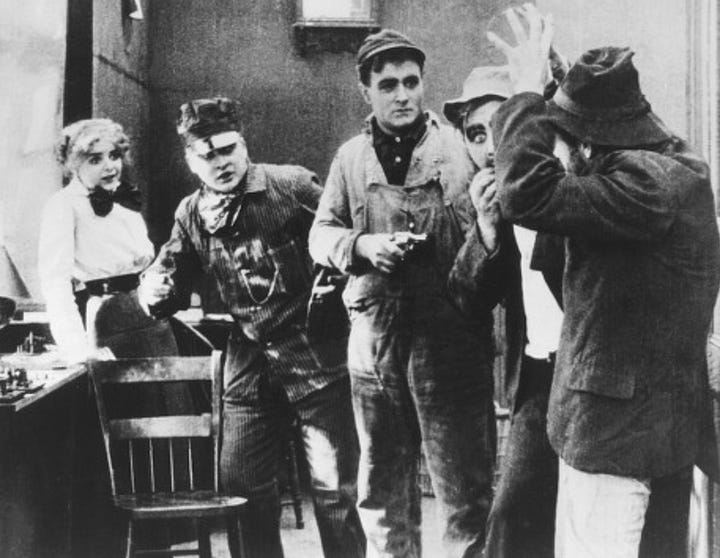

The Lonedale Operator stars a moon-faced Blanche Sweet playing a telegraph operator for a remote mining concern who, taking delivery of the company’s payroll, finds herself in a pickle when a pair of ne’er-do-wells attempt to jack the bag of money from her.

What ensues are three intercutting strands of story: Blanche barricaded in her office, the criminals attempting to break inside, and a rescue train whose driver is the gruff, heavy-jawed love interest played by Frank Grandon.

Griffith used bloody red tints for the train shots to better convey the ferocious heat of its engine, and the whole affair clips along with some nicely naturalistic exterior shots shot aboard the carriage. We get a feel for the momentum.

But when the train eventually arrives (how long it takes!), Sweet has already bested the burglars by jabbing a wrench in their faces, which they mistakenly confuse for a pistol. When big lunk Grandon rocks up, all gnashing jaw and rotating shoulders, Sweet reveals her deception—and Griffith rewards us with a close-up of the wrench. It’s a real “ta da!” moment. Even the burglars bow.

Elsewhere, this writer is right to celebrate The Lonedale Operator’s subtly emotive composition, where Griffith frequently places his characters “at the left of right edge of the frame, which creates a sense of imbalance and tension”. He also pushes his camera forward while Blanche Sweet taps furiously at her telegraph machine—better accentuating her mortal terror. We’re in the room with her.

The close-up was novel, but Griffith’s film also shows off his deft technical grasp and cinematic maturity; even when he was dealing with the most schlocky of scenarios. In time, he’d be telling very different stories.

In these early years, the close-up could be many “things”. For some, it offered a means to draw attention to important narrative details that might otherwise get lost. Think about Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde—a Thanhouser Coy. flick from 1912. In the film’s last gasp, Mr. Hyde’s curling, seemingly-but-perhaps-not prosthetic hand grips the poison he’ll use to end his life. In this instance, the close-up solved a narrative “problem” for Lucius J. Henderson, the film’s director; helping to keep the momentum going without relying on a disruptive intertitle (e.g., “Hyde drinks a deadly poison!”) It’s also quite fun, even if it’s the only image you’d probably want to save from this otherwise pedestrian adaptation.

Formal innovations are like sea foam; they spume out at the tops of waves and then get lost just as easily as they came. It’s hard to say whether G. A. Smith’s audience saw his telescope and thought, “the cinema is changed”. This is the backwards-cycling perspective of film histories, which all but feed on observations like these.

It might feel more like a kind of advancing-accumulating-sedimenting thing, where filmmakers were toying around with new tricks and devices that entered their collective lexicon but weren’t always picked up or sustained. Just because G. A. Smith gave it a spin in 1900, it doesn’t mean that every other filmmaker started using them with headless abandon.

Given another decade and loose change, however, close-ups had become part of the filmic furniture. Just think of Louis Feuillade’s obsession with them in his episodic Les Vampires (1915-16)—or Giovanni Pastrone’s up-close adoration of rings and treasures in his sprawling Cabiria (1914). The close-up untethered filmmakers from the disruptive fussiness of intertitles, just as it drew attention to things that the audience needed to take note of: bottle of poison, wrench, exposed calf. Etc.

In other words, film was already beginning to look a lot more film-y as the years wore on; which you might indulge in me as a kind of rotten English version of the French “photogénie”.3

It also makes me wonder what we mean when we say that a film “looks like” a film; implying some kind of teleological process by which cinema arrived logically and coherently toward its “final form”; which can’t be true, and isn’t true. But more about that later.

This website has that perfectly pearlescent realness that you find with the old internet’s unrelenting hobbyism; it goes into some detail about G. A. Smith’s film and business interests in Hove during the late 1890s and early 1990s, including the buildings he leased, who he leased them from, and what he got up to there.

In the history books, Williamson’s reputation lies mostly in the production of cameras and equipment; with devices he patented still exchanging hands into the 1940s. Like Smith, he was an early exponent of narrative editing and reverse shots.

There’ll be time to talk about “photogénie”—that curious facet of French impressionism—in later posts. For now, this piece by Marcell Bardos covers the ground in a lot of useful detail.

This totally reframes how I think about early cinema. The detail about Williamson chalking focus marks on the ground for The Big Swallow is wild—I tried filming a close-up shot last year and just assumed my camera would handl the focus automatically. Realizing those early filmmakers had to invent even basic shot composition through pure trial an error makes me appreciate how much visual language we inherit without even noticing.