1.1 – Fatal attractions

The birth of cinema in Belle Époque France (1888-1900)

“The cinema is an invention without any future”

Louis Lumière

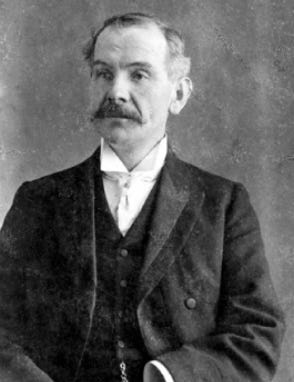

We all know the things we know about the invention of cinema. The tidy Hallmark story tells how Auguste and Louis Lumière—two French brothers and businessmen living on the banks of the Rhône—came up with the “idea” and made it a sensation.

It’s a plumply whiggish story; satisfying our desire to trace the roots of film to a single, coherent point. But the reality—as is so often and excitingly the case—has all kinds of lumps and bumps and dog-legged angles that don’t fit this too-tidy narrative.

In this spirit—and in the interests of what actually went down—I want to use the first entry of my history to tell a muckier story. It’s one, care of industrial secrecies, financial mishaps, disappointments, and acrimony, that—in 1897—blew up in a tragic fire that nobody could have foreseen.

But—to put a lighter and smiling face on these affairs—these same years began without the cinema. By 1900, as Henri Langlois put it—France’s beloved film preservationist, famed for his floppy hair, wonky tie, and bulbous eyes—“cinema sprang from the trees, gushed from the sea, [and] every screen opened a window onto infinity”.

Things were about to get reel.

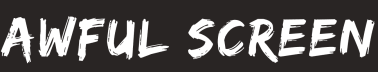

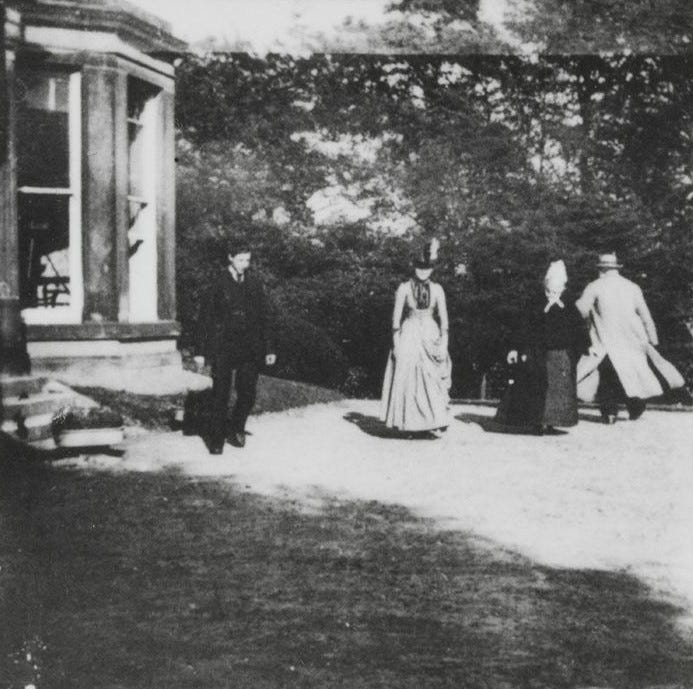

First things first, it was another Frenchman—Louis Le Prince—who beat the Lumières’ to what is commonly thought of as “their” invention. His Roundhay Garden Scene (1888) is a 2 second “shot” (lest we think of it as a film in the fullest sense of the term) that documents ‘little’ more than a group of smartly-dressed bourgeois standing and strolling around an English garden. This took place in Leeds, England, making the UK—and a notably rural corner of it, at that—the unlikely place for the film revolution to take off.

Despite its brevity, Roundhay Garden Scene was the first “film”—that we know of1—in the proper sense of the word; and we might compare it to that first photograph taken by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce in 1827. “View from the window at Le Gras” depicts a smudge of densely dark shapes and twisted forms that, squinting and blinking, we have to believe are a horizon of rooftops. It is not too dissimilar from the murky, imprecise forms and hollows that dominate Le Prince’s film—gaunt blocks of body and dress tangling their way through the cinematic darkness.

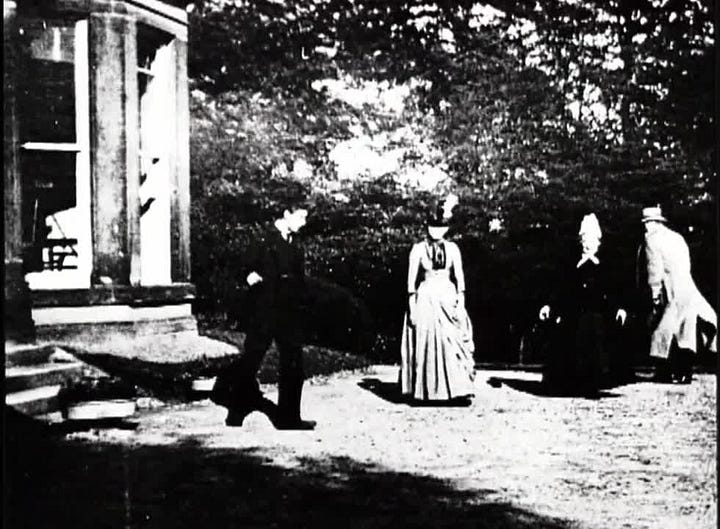

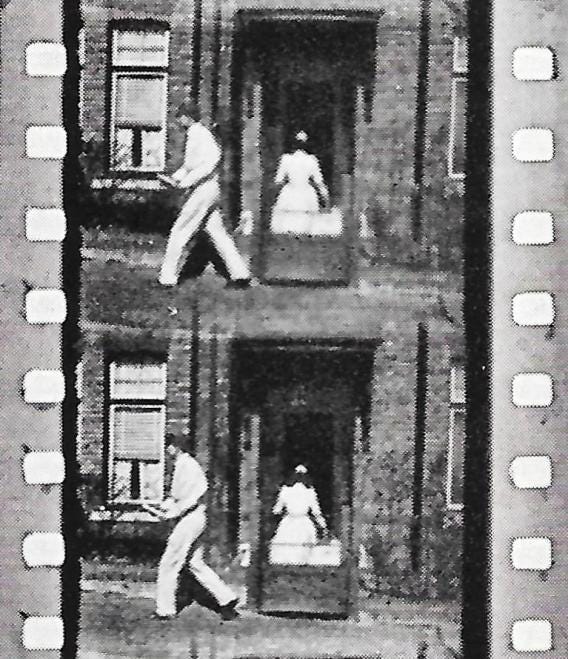

But how did le Prince do it—and in what ways was his approach both similar to and different from that taken by the Lumière brothers? His machine (the “receiver or photo-camera”), patented in the US and UK in 1888, was a combination of both camera and projector (which he called the “deliverer or stereopticon”). Like his contemporaries, he had to devise a device that could smoothly pass photosensitive film through its aperture; capturing not just a “single” image but a series of consequential “frames”. By divine conception or a canny reading of patents and photographic journals, Le Prince understood—like the Lumières, Edison, and myriad others—that sprocket holes punched in the film strip would ease its passage through the machine. The same technique would subsequently pass exposed film through the projector, creating the illusion of perpetual motion—turning discrete, frozen images into movement and motion. Film’s first “problem” was a matter of movement.

But Le Prince was able to “solve” this problem—thanks to various American patents and innovations, mostly shoved and hurried along by George Eastman of Kodak2—and it was with his sprocket-holed, hand-cranked device, on a mild October day, that he shot his first—in fact, the first—film. We’re led to believe that his equipment was also capable of projection (his assistant, James Longley, noted that Le Prince projected his films in his private workshop, though no public screening ever took place). We have to believe him; and why shouldn’t we?

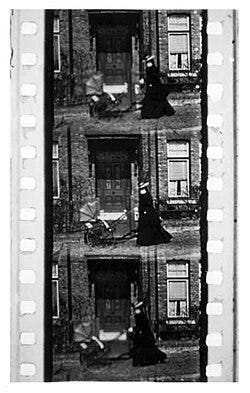

Contemporaneously, figures like Willian Friese-Greene and Wordsworth Donisthorpe—both Englishmen—were pursuing their own parallel experiments, which the former patented in June 1889 and the latter as early as 1876—though Donisthorpe wouldn’t present anything like a “moving picture” until 1890, when he documented passing traffic in London’s Trafalgar Square. Meanwhile, Birt Acres conducted his own experiments; using his portable (and funnily named) 35mm Birtac machine, alongside Robert W. Paul—who we’ll be hearing a lot more from in future entries—to capture such films as Incident at Clovelly Cottage in 1895, though he wouldn’t publicly screen his films until 1896.

The case of the German Skladanowsky brothers, meanwhile, is more interesting; nudging at the idea that the Lumières really “came first” (so far as public projection goes). Using their Bioscop machine, they hosted a public screening in Berlin’s Wintergarten theatre—in Berlin-Mitte—on November 1st 1895, two months before the Lumières held their own public screening at Le Salon Indien du Grand Café in Paris.

The Skladanowsky’s event featured eight films, mostly between 6 and 11 seconds in length, looping continuously while a specially composed score drowned out the sound of the whirring, clacking machinery. The show would travel on to Berlin and Paris, around the same time that the Lumières were promoting their own demonstrations. The programme itself (which you can view online) features dancers, acrobats, boxers, jugglers, and wrestlers—all of it shot outdoors, in full sunlight, against a white or black backdrop. In other words, it was a typically vaudevillian display that might otherwise appear—“in the flesh”—on stages across the city where the programme was screened.

What should become clear—through all of this—is that there is a great deal of temporal ambiguity, industrial suspicion, and wrangling of patents surrounding the proper “invention” of film; and different histories and historians use different yardsticks to measure that much-desired holy grail of being the “first”. It’s easy to get lost.

In his writing on the early cinema, Stephen Barber talks of the “shattered and gutted projection boxes”, the “dust-encrusted cans”, and “now-decrepit auditoria” of the first cinemas and cinema palaces. He is right to underline how the very earliest days of film were beetled by an obscurity from which a coterie of long-forgotten “also rans” come down to us in fragile whispers, their hands clasping at mouldy fragments. There was money here, but for every successful Lumière—and even the Skladanowsky brothers charged as much as 2,400 marks for their early showings—there were those whose fate was to try, and fail, or to succeed in the wrong way—or too late. The history of cinema is a kind of excavation; and it is throttled by all manner of cobwebs and delusions.

Regardless, it was the Lumières—with their established photography business, workers, and factory—who had the necessary capacity to start making films and film cameras on a more industrial scale. They were keen-eyed businessmen who were well positioned to beat out the German Skladanowsky brothers through a sustained and clever PR war, while certainly benefitting from later (primarily French) accountings that gladly pushed their native-born sons to the front of the proverbial picture. In the early years, the story of cinema was French; but Germany would most certainly make its comeback. Given time.

The brothers’ equipment—or, more properly, their system—was called the Cinématographe; using a name which originated with fellow countryman Léon Bouly who, for want of financing, had to drop his own efforts. What was bad for Bouly was great for the brothers. He is “just” another figure who fell by the wayside.

Wim Wenders’ A Trick of the Light—made in 1995—honours and adores the “successful failure” of the brothers, centring on a charmingly interpolated interview with their now 91 year old daughter. In her light-filled Berlin home, she—with brisk familiarity—handles the artefacts and fragments of her father’s cinematic machinations: photographic “flick books”, hand-punched film reels, plate-glass negatives. It’s a keen reminder that the Berlin brothers were not industrialists, like the Lumières, and had to muddle their “hand-constructed” Bioscop together in their tiny Pankow apartment.

The Bioscop was good; it worked. But it couldn’t achieve the crispness of images, the flowing of motion, nor the durations of time that the Lumière’s technologically superior device could obtain. The brothers—playful and serious and artful and larking—had to make do with being the “forgotten first”, just as Bouly had to concede the race.

Things were moving fast.

Like the Skladanowsky brothers’ device, Lumières’s camera-projector was a relatively lightweight, hand-cranked machine that was capable of producing sharper images and better illumination than Thomas Edison’s “kinetograph” across the pond. It also featured a projector; allowing it to cast its image onto a screen for public viewing. Edison’s Kinetoscope could not do this, requiring a special “peep show” projection box; meaning that only one person could view the films at any one time. This would turn out to be very important, and would hold back the American film industry while their European counterparts were figuring out how to turn film into a collective spectacle rather than a private “trick”.

When you look at it today, the Cinématographe doesn’t look all that dissimilar from a modern camera body; and you’ll quickly recognise the familiar relationship between lens, body, and viewfinder. Even perforations in the film allowed for it to be passed through and projected in a way that would provide a stable and continuous image. This was enough to ensure that their device would gain popular and rapid appreciation. When the Skladanowsky brothers saw the Cinématographe in action, they saw the future; just as they saw the limitations of their own (sadly inferior) invention.

But they had all benefitted from parallel efforts in cinematic invention, and figures like Le Prince should be thought of not as loners beavering away in their ivory towers—but there is a grain of truth to this—than technicians and businessmen who worked along parallel albeit not always overlapping trajectories like a ragtag and dispersed collective who were tumbling toward the “finish line” in a whirlwind of jolts and jumps. In some senses, the arrival of film wasn’t an “accident”—and it may even seem inevitable from a later remove. If Le Prince hadn’t got there first, it’s probable that other inventors would have eventually figured it out. Similarly, film didn’t depend on the industrial capacity offered by the Lumière brothers—but it certainly benefited from it. Bouly’s only impediment was that he ran out of cash; if he hadn’t, the history of film might look (at least slightly) different.

Either way, having cracked the problem of projected motion, this “invention” would—in its first few years—give rise to what film historians call the “cinema of attractions”; where films were really a kind of fairground diversion featuring an “actuality”—a real thing in the world—that had been inscribed through the magic of photographic movement. In just a small amount of time, these silent films—though “silent” doesn’t quite capture the sonic texture of the contexts in which they were projected and watched—acquired their own “language”; and they were inventing it in real time.3

Early attractions (or “actualities”) were short affairs, and they would often be strung together in programmes that audiences might wander into and out of. For the Lumières themselves, that very first work was Workers Leaving The Lumière Factory in Lyon (1895, 46 seconds long): a film that everybody knows and which has gained such a place in the zeitgeist that it has been memed, ripped, copied, and even sent up by The Simpsons. Elsewhere, The Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat Station (1896, 50 seconds long) is another early and notorious film, not least for the (alleged) panic that its first screening induced—though there’s no hard-and-fast evidence that such a freak out took place. For Ray Zone, “a panic legend became the founding myth of the medium”. Remember that.

Hito Steyerl, writing in her typically allusive manner, suggests that when the Lumières’ workers were filmed leaving the factory (chatting, shoulder to shoulder, seeming to glide rather than tread), they carried not only the industry but the idea of film along with them, “dispers[ing] it into every sector of life”. They were now not only workers but subjects of film; and, soon enough, they would become spectators of film, too—forming a newly industrial ouroboros of worker-watcher-worker. But we can only speculate what they felt when they saw themselves projected on the first cinema screens. I like to think that they found it all very fun, despite Steyerl’s cautioning against how this heralded a new era of surveillance and imagistic exploitation.

The actuality film, however—of which these workers were now a part—was not yet a singular thing; and cinematic “genre” was still so slippery and diffused an idea that surviving works come down to us as a kind of kleptomaniac fever dream; begging and borrowing from the expansive costume cupboard of theatre, pantomime, photography, sculpture, and painting. It might have seemed a novelty to some; especially those who’d seen any number of recent inventions arrive just as quickly as they disappeared.

For their own part, the Lumières were sceptical about the long-term relevance of the cinema; infamously declaring that it was an invention “without any future”. It’s for this reason that they would eventually cease production of actualities and drive their business toward the manufacturing of cameras and equipment; though they snubbed Georges Méliès—again, we’ll be hearing a lot about him—when he offered to purchase one of their machines. Intellectual property was everything.

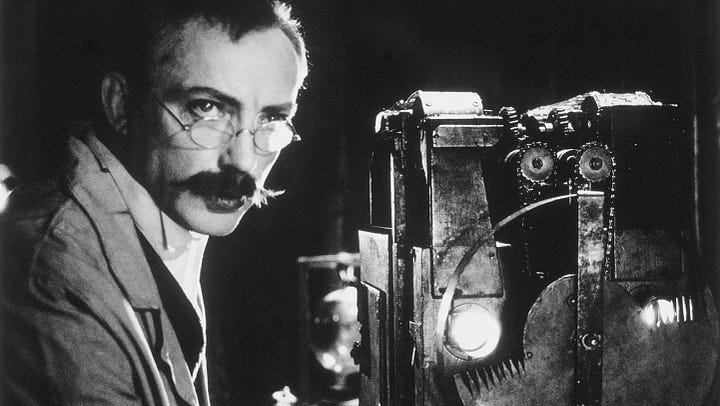

In fact, this is a good opportunity to digress about Méliès—that illusory and unbelievably influential alchemist who cut such an interesting figure in the early cinema of France.

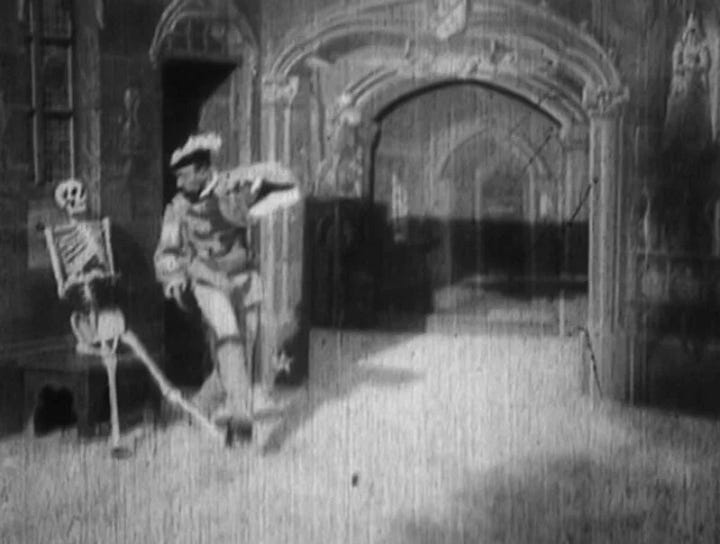

Let’s call him a kind of grandfather-come-wizard of silent film who surfaced from the throng of early actuality-hawkers to cement his place as cinema’s first great illusionist; using tricks, trompe l’oeils, and slights of hand to create phantasmagoric spectacles that ran the gamut of magical conjurings, cave-dwelling demons, and the illusion that Méliès’ own head had been cut off.

They are magical, decadent, and delicately Belle Époque in their realisation; showing the influence that the popular illustrations of Gustave Doré had on the prolific Méliès. He also made more “conventional” actualities; filming festivities and fêtes and life on the streets. With his tricks, exposures, maskings, and illusions, Méliès demonstrated that film was a device that doesn’t just show us the world, but constructs it; preparing the ground for such revolutionary advances as montage, even if these developments would only come “much” later.

Brief digression over.

In these first years of film, it wasn’t yet obvious that the cinema would become a “narrative” vehicle; as one that might involve different perspectives, locations, temporalities, and characters. The first studios and filmmakers were held back by costs, technical faff, and questions about audience reception (who would want to see this), even if they were already clueing up to the idea that films might make excellent vessels for longer and more complicated stories. For now, however, most producers were limited to making short, single-shot films from fixed camera positions; with most being little longer than 10 or 12 seconds. These were hardly the conditions in which to adapt Moby Dick. For now, at least.

Broadly, however, it’s argued that the first proper “story”—and we will get to this in my next entry—was La Fée aux Choux (1896): a now lost film directed by Alice Guy-Blaché (later Alice Guy), who we should rightly think of as one of film’s earliest and most important innovators. She experimented artfully with such devices as colour-tinting, special effects, and sync-sound, and would later go on to found Solax Studios in New York—one of the many businesses that bolstered the early New Jersey film industry, before it upped sticks and headed west for California and the coming stars of Hollywood.

Guy remade her film several times, but only the two later versions now survive. The surviving 1900 version—which is 70 seconds long—features a single static shot depicting a fairy who appears to pull babies from cabbages. The earlier film of 1896 seemed to have a more complex scenario and three additional characters, but we have nothing to go on aside from Guy’s retrospective accounting. It has been argued that this earlier version was likely shot on a wider format, seeing as Guy describes characters “jumping into the field of focus” and mentions people approaching from a distance. Even then, the later films—from 1900 and 1902 respectively—retain a single-shot structure that reveals how film was still broadly “borrowing” from the conventions of the stage; and we do not yet have the closeups, cutaways, or reverse shots that would become increasingly dominant through the pre-war period. This is certainly a story that we’ll get into in a later post.

Elsewhere, a coterie of mostly French, German, American, and English filmmakers got busy with producing their own actualities—a great many of which have been destroyed or lost. Taken together, we can glean a pretty nuanced picture of the kinds of subjects that interested these Edwardian and Belle Époque audiences; ranging from views of Niagara Falls and panoramic scenes of the Champs-Élysées to subway rides and steeple chases. We also get films documenting tragedies and natural disasters, including the aftermath of the San Francisco earthquake. There were episodic tales of Rip van Winkle, an observational film of a man drinking a glass of beer (whom we don’t need to “imagine happy”), and the earliest known adaption of Shakespeare. Whatever might “fit” into a short canister of film; whatever the filmmaker felt moved or tickled by; and whatever the early studios thought would go down well with their audiences. It was a lot.

Remember, this was all happening between 1896 and 1900. The cinema made a heady and immediate splash, even if it wasn’t yet certain how it would evolve and develop. The names of influential early producers probably won’t ring a bell, either; including Cecil Hepworth, G.A. Smith, James Williamson, Robert W. Paul, some of whom—by 1899—were making as many as 100 actualities a year. Now the technology existed, audiences came forward; hurrying and curious and eager to see what all the fuss was about. They were hooked.

In today’s entry, I don’t want to get too far ahead of myself; and we’ve already covered a feverish and fertile flurry of early filmmaking that I’ll need to eventually retread. There’s the story of the Lumières’ disciples and trainees—people like Francis Doublier—who would bring the movies to Russia, Hungary, and many other countries. There’s the parallel arc of how the earliest films took off in England, Sweden, America, and Italy—but, again, these are tales for another day; even if I won’t be able to tell them all.

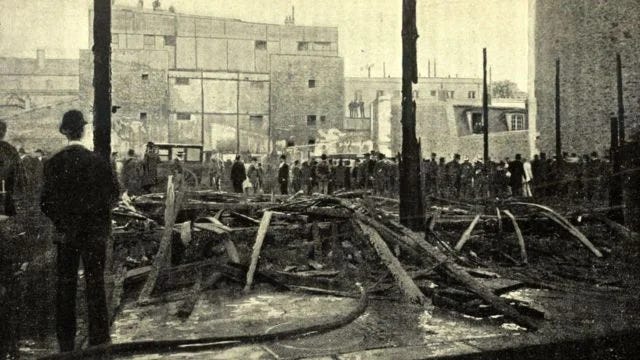

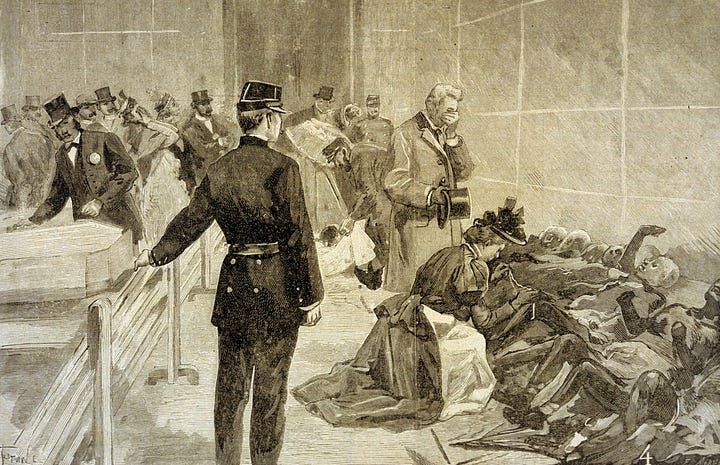

We’ll close out this first entry with an event that foreshadows some of the detail I’ll be getting into later around projection and chemicals—and this is the tragic 1897 fire that gutted the Bazar de la Charité: an annual charity event organized by the French aristocracy. For its 1897 edition, the Bazar was located inside a large wooden warehouse at 17 Rue Jean-Goujon, Paris, and had been worked up to look like a medieval street. Its primary attraction was a Cinématographe installation that would screen any number of actualities to fee-paying audiences. I’ve been unable to find a detailed listing of the films that were shown but, given that they were using a Lumière Cinématographe, we can only assume that the programme was made up of Lumière actualities. Let’s picture workers, trains, and walls being knocked down.

On the afternoon of May 4th, however, the projectionist’s equipment caught fire; causing a raging conflagration that killed 126 people. The story attracted fervid speculation and press coverage both in France and internationally—and its cause can most likely be chalked down to the highly flammable materials that early film stocks were made out of, though other reports cite the accidental ignition of flammable ether. While it might not have been the first film fire, it was the most widely reported—and certainly the most sensational.

There is some suggestion, as a result of the fire, that it became “unfashionable” to attend the pictures. Yet, Ian Christie—in Robert Paul and the Origins of British Cinema—remarks that there’s no meaningful evidence to back this claim up, and—as we’ll see in later posts—film “palaces” and cinemas were about to become a huge, popular business not only in France but around the world. Even then, the Bazar would not be the last fire to terrorise film audiences, nor to obliterate its archives. But people weren’t “put off”. Not by a long way.

This is all to underline what film had become by 1897, all within a year of its first public “revelation”. It was popular, it attracted massive audiences from across the social classes, and it was still tremblingly new. Many died on that bitter afternoon, and the cinema—in that moment, the embers still hot to the touch—might be imagined as having tripped fatally up.

But this wasn’t to be its fate.

There would be other fires; more fires. Film would come to document life as it was lived and dreams as they are fantasised. Given time, it would record such horrors and catastrophes that Louis Le Prince, nor any of his fellow inventors, could have imagined or realised.

Later, in the faraway year of 1980, Jean-Louis Schefer—occupying the once unimaginable position of a theoretician of the moving image—would suggest that we do not watch film, but that film watches us; peeping inside the “invisible chamber” of our “interior history”. Its light burns through us; swallowing and gulping the air that hangs above the heads of us of those who spectate it. It renders us almost passive; a subject of flickering light.

In Leeds, in the autumn of 1888, Le Prince had stirred something unbelievable up—and it was now much too late to put the genie back in its bottle.

This is where I’m going to stop for this first part of my lopsided history. I’ve probably covered too much ground too quickly, but I’d like to think that we’ve at least laid the foundations for future entries. We know “when” film happened; we know who some of the principal players were; and we appreciate how popular and well reported its activities became. We also “get” what kinds of films were being made, and how they were patronized by aristocrats and workers alike.

To modern eyes, these films still feel very shaky and primitive; and there’s no indication—not yet, at least—of what was to come, nor of how rapidly that change would come about. In my next entry, however, I’m going to look at how film first embraced stories and narratives; moving from shuddering fairground attractions to heart-stirring melodramas, science fiction fantasies, and epic dramatizations of violence and tragedy. This part of the story will take us from 1900 to 1906.

See you next time.

Keen-eyed readers might point out that Le Prince had shot a slightly earlier film of a bridge in Leeds, called Traffic Crossing Leeds Bridge, in 1888. Mark Cousins, in his history of film, alights on this as being the properly “first” film, but I really don’t want to get too muddled about this. Garden or bridge; let’s just focus on Le Prince.

Eastman’s Kodak debuted in 1888. It was a photographic camera whose innovation, for the motion pictures, was its ability to advance the reel using “sprocket holes” and little grabbing nodules. In a November 1889 advert for the device, the copy is really quite humble about its achievement: “You press the button—we do the rest”.

By which I mean, we have to imagine the noise of the projection—a whirring, clacking, clattering burr—as well as the noise of the screening itself; with all its chatter and rustling. There’s also the fact of scores, musical accompaniment, and live narration that also attended these early events.