There’s a really good chance that next week’s newsletter won’t happen — and this is because I have to put the finishing touches to a long essay on Jean-Daniel Pollet. It will be appearing in a book of essays early next year — a rare foray into print. I really need to knuckle down and get it done. Apologies for the potential radio silence! I’ll make sure to properly promote and link to where you can get the book once it comes out.

— Armenia, October 1969. Parajanov completes The Colour of Pomegranates. It receives its national premier only after some quite messy state-imposed chopping has removed all but the most elliptical references to Sayat-Nova, the ashug (singer/poet) whose life the film is about. Nearby, in neighbouring Georgia, Giorgi Shengelaia completes Pirosmani (also 1969), a life of Georgian primitivist painter Niko Pirosmani.

— Ten or more years have passed since I first watched The Colour of Pomegranates. Eleven or twelve hours have elapsed since I first watched Pirosmani. Parajanov would — later, after being released from prison — make his own film about Pirosmani (Arabesques on a Pirosmani Theme, 1985). They are both — to lesser or greater degrees — kunstler (as G put it), a life of the artist. Shengelaia’s film is more obviously a linear ‘life’, and is more obviously concerned with Pirosmani’s art and its reception (and neglect) within his milieux at the turn of the last century. What both films share is a kind of similarity of aesthetic strategy. They are both formally constructed around tableaux – around largely static scenes and a kind of reverse-forced perspective (i.e., they squash their depth and attempt to assemble a kind of canvas surface within the frame of the lens). Messily, you could say that Pirosmani often looks like the artist’s own paintings (often, not always), and that The Colour of Pomegranates looks a lot like a religious icon (albeit ‘come to life’).

— I think their similarities end here; more or less. Parajanov’s tableaux are grouped around a sequence of poetic, interpretive gestures and bodily positions — elliptical loops that have been yanked from the representative naturalism of real life. Shengelaia at times brings his camera backward and forward (fixed, on a tripod); he pans and tracks (in the film’s opening moments, he pushes through one room — assembled like a canvas — and into another, before panning to the right slightly as if to capture another surface beyond it). Parajanov obliterates depth. His gestural constellations (woman pouring wine on man’s chest; an ocean of books drying in the wind; a devil slapping the skin of his drum) can appear uncanny, even eerie. Not of this world. For Shengelaia, reality and the painted surface are sort of held in tension – overlapping, trembling, but ultimately coexisting. His very painterly compositions can often loosen up and become a lot like real life (how a scene — a painterly scene — unfolds into naturalistic movement and conversation). Either way, it’s still very curious that they were both exploring the tableaux (to different interpretive ends) in the same years – as a formal approach. I have to assume that they talked or shared ideas or work. Maybe they didn’t. But I don’t think that S is trying to confound our perception with his tableaux (like Parajanov), but is rather trying to deepen our understanding of Pirosmani’s perception (how he translated life onto/into his canvases). This might be the difference. But.

— There are some vague overlaps between their lives (Parajanov/Shengelaia). They both made films about Pirosmani. I think there’s a very good chance they met and socialized (later, if not earlier). Marcello Mastroianni visited Tbilisi in the 1990s — hosted (as far as I can tell) by Shengalaia’s brother, Eldar Shengalaia (also a filmmaker). They hung out with Parajanov. Parajanov gave Mastroianni a pair of shoes (his?). Earlier, in 1973, Giorgi made Melodies of the Vera Quarter — a film starring Sofiko Chiaureli, who is thought to have been Parajanov’s muse. They both shared a very keen interest in the material/traditional cultures of Georgia and the Caucasus. They both explored the potentials of flattened perspective and painterly composition. Unlike Parajanov, Shengalaia’s film was met with a great deal of praise and prizes.

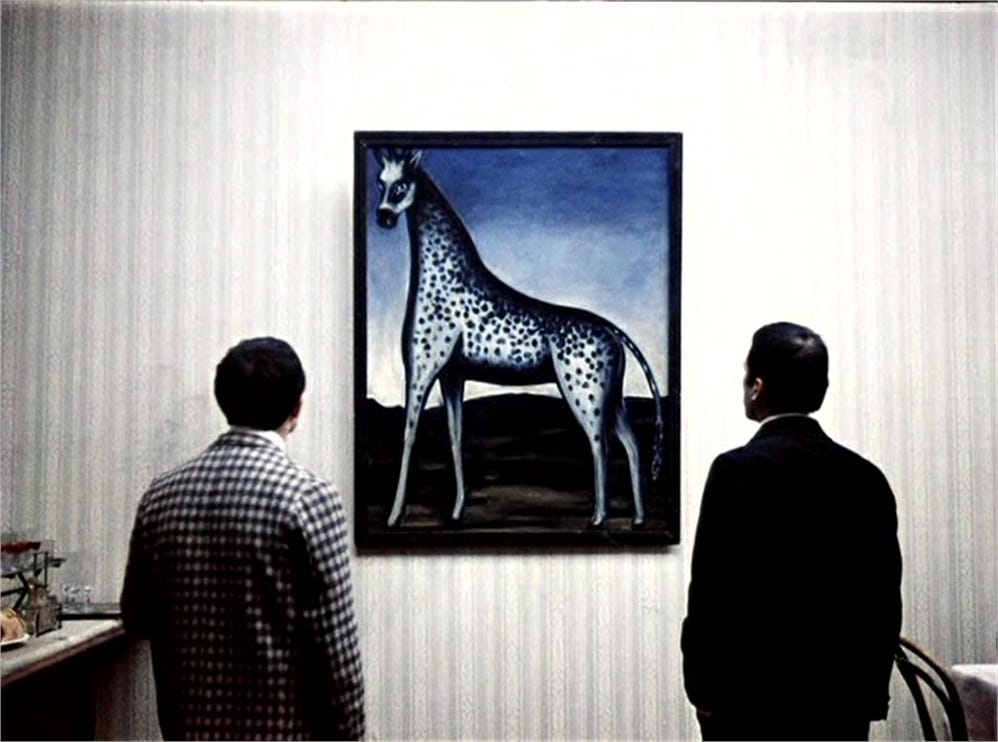

— I think it’s fair to say that Parajanov’s film — in more absolutely and rigorously adhering to the sublimity of the elliptical tableaux — is more successful. Where Parajanov’s film is haunting, Shengelaia’s is more naturalistically dramatic. Pirosmani — as a historical and, as it were, literary figure – is presented to us in a more or less rounded-out psychological light. He speaks at length. We understand his anguish and his accomplishments. The film follows him (sort of) from his youth (skipping a handful of years) through to his later life (grey hair, eyes cast down). We learn very little about his methodology (as a painter) from a processual perspective, mostly because we rarely see him painting. We often greet him just as he’s accepted or is completing a composition. The painting seems to happen elsewhere, is remaindered away (a few taps of a brush against the oil-cloth). We learn about his cantankerousness, how he has been “stuck in the throat of this life” — a sweet man whose sensibilities set him at odds with the so-called “mercantile” world in which he lived. We often see him drinking, padding between the taverns and bars whose owners commissioned his works (which would decorate the otherwise plain walls). Shengalaia inserts various paintings by Pirosmani into the film. Their bearing/relation to the scenes on either side of these insertions isn’t made clear. They serve as non-lexical intertitles, and remind us of the strange, extraneous richness of Pirosmani’s canvases — things which explode from the tawdriness of cellar rooms and fusty furniture.

— There’s a whole other narrative within the film concerning the artist’s relationship with the bourgeois art establishment of 19/20th c. Tiflis. Through the first half of the film he is pursued by two academic painters who, by chance, encounter his paintings in a rural restaurant and go in search of the man who’d created them. Pirosmani (a ‘naive’ painter — untrained, self-taught) sort of bumps sensitively against them. His work is championed and – subsequently — spat out. There’s a very emotional scene in which a dejected Pirosmani is told that the whole city is laughing at him, and sees an unpleasant caricature of himself (sack-clothed, bare-footed) in the city’s newspaper.

— The torment/agonies of Pirosmani are — for Shengelaia — much more immediate, much more everyday. Parajanov’s trials (and agonies) are — in The Colour of Pomegranates — of an ecstatic and erotic-religious nature; the auratic, trembling force of poetic inspiration and divine visitation. But they both share a similar concern with the flattened plane, the unsteady/uneasy relationship between the flatness of the painted canvas and the depth of corporeal space. But Shengelaia is more flight of foot in how he explores these potentials — using long tracking shots to follow Pirosmani as he walks through the streets of Tiflis, of how he (often) pushes into a space, a room. As I said earlier, above, he works with the tension in/between painting and cinema — its impressionistic tableaux coexisting alongside a more naturalistic formal arrangement of bars and taverns and fields. Nonetheless, like Parajanov, he was very capable of arranging his figures in space — poised, repetitive gestures, etc — and of injecting them with the tonal palette of Pirosmani’s own work (a palette that is both richly vibrant and darkly muted). It’s worth noting that Avtandil Varazi — who plays Niko Pirosmani — was himself a painter, and played a role in the art direction of the film.

— Pirosmani fixates itself on the personal fortunes of a single man — and the subtle irony that this figure (eaten up and spat out by his contemporaries) has become among Georgia’s most celebrated artists. Shengelaia demurs from constructing a necessarily hagiographic account of his life — cantankerous, prickly, yet profoundly empathetic — while also narrowing his eyes at the idea of Pirosmani’s unsoiled reception among his contemporaries. He sides with the artist. Even those most sympathetic to him (as man or artist) are seen to be self-serving, venal, even openly callous. His is a social history of a personal artistic journey. The Colour of Pomegranates arrives as a euphoric and difficult confrontation with the genius of poetic inspiration — of a Benjaminian aura. But they both — as I’ve said above — share a (more than superficial) similarity in terms of their aesthetic agendas. I just think that Parajanov took the tableaux to more interesting places (perhaps precisely because he was not attempting to merely recreate paintings on strips of celluloid, but to capture a very different kind of mimesis).

— That being said, Shengelaia’s film is very, very beautiful and at times quite sublime. Its ironies and humour help to disentangle it from pure hagiography, and they offer a biting critique of the alienation and extraction at the heart of bourgeois artistic institutions. For Parajanov (who actually found himself much more in conflict with those institutions), the struggle is emotional, personal, erotic, divine.

If you liked this newsletter then please consider liking, sharing or subscribing. It’s lonely here.