The big sweat

Pores and paranoia in postwar Japanese cinema

Japan, the 1950s. Muddling out of the privations and iniquities of war, filmmakers—let’s think of Kurosawa, Nagisa Ōshima, Kō Nakahira, and Kaneto Shindō, but there are many and diverse others—began to get grimy with a ragged bunch of police procedurals, criminal spats, family bustups, and business deals gone wrong; all of them oiled by a cloying, sweaty heat. It was the “golden age” of Japanese cinema; it was becoming too hot to handle.

Memories of Hiroshima, or an uncomfortable embrace with commerce and capital—or why not both; as Japan grappled with its past and set its eyes on its future (there’s a neat, handheld bit of blurbing for you), the country convulsed with images, and realities, of criminal desperation, loosening morals, and an unkickable dope habit—all of it, as Akira Lippit argues, tangling together into a new cinema that was at once national (Japan as it saw itself) and international (Japan as it was perceived by a global community of film festivals and their audiences). Sweat seeps through as the unctuous cinematic symbol of a society that trembled with all manner of “beasts” and “bastards” (or so the long-haired mouth of Seijun Suzuki put it). Nobody—in this clammy climate—was spared the inclemency of this weather.

The big sweat—let’s call it that—is a heat we can see; one that reaches out and sticks to us. It is a heat that characters slither and struggle through; mopping their heads with grey kerchiefs, blinking intrusive beads of sweat from their eyes, fanning themselves dully and compulsively as if the heat—this heat—was not only the greatest calamity to befall them, but as if they are powerless to put it to an end. The big sweat leaves its thickening mark; staining shirts, oiling brows, and pressing down upon characters—who are almost always town-dwellers and urbanites—with its inarticulate and inescapable schmalz. Yes, the big sweat cannot be sweated out; nor can any amount of fans, cold cloths, or glasses of water dispel it. The heat is simply too much.

First, I thought the “big sweat” was simply a condition of cinematic production in postwar Japan—the necessity of bright available light and summer-long shooting; but the more time you spend with the big sweat, and notice it pooling toward you, the more it comes to feel like a necessary instrument—a forward and highly signifying device that is doing no small amount of fanning and waving of its own.

In Kaneto Shindō’s Heat Wave Island (1959)—a rare emanation of the “big sweat” for the film’s quite literal invocation of it—this heat makes itself immediately known; bright beads of dew clinging to the naked arms of policemen as they go about solving the death of Otoya, played cunningly by Nabuko Otowa (who has just been disinterred from the sun-baked earth). Beads of sweat on exposed shoulders, sunglasses glinting with the ceaseless sun; the uniform of the big sweat is its pervasiveness, its glomming over everything. Shindō offers the rare and languishing respite of wind-whipped flags and water—the passing sight of ferries and boats crossing the island’s water. But it’s never quite enough.

For Oishi, the lead detective, the beauty of the island’s pale granite “is a symbol of poverty”; where the fields regularly wash into the sea, giving up their meagre crop of wheat and potatoes. Shindō is telling us, cynically, that purity cannot survive—and that beauty is always and already compromised. It is here that a Japan Democratic Party boat cruises past (wide shot, a lot of sea to eat up) its agitators appealing over loudspeaker—without a lick of irony—to these “islands bathed in abundant sunlight”. But the waters are already poisoned (no thanks to the factories and industry that replaced the fishing that once thrived here)—and its citizens have been pushed to the limits of toleration.

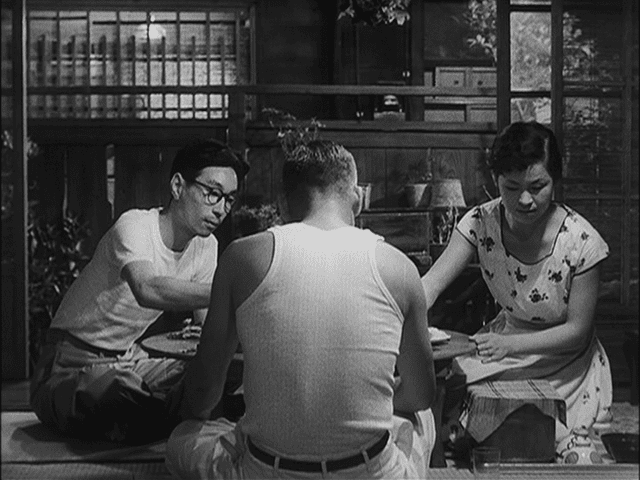

Otowa—in flashback, we see her before her death; pieces of the whole shattering toward us—leans down, smirking in her sweaty silks. The camera angles down over the nape of her neck, a great glistening on the surface of her body. The heat—and its unavoidable sweat; the body’s merest defence mechanism—is the pallour of every dirty bit of business that this paradisiacally poor island in the Seto Sea has become “infested” with: prostitution, fraud, corruption, pollution. The heat presses down; it renders everything sluggish. Michiko—the film’s “not-quite-innocent” innocent—looks up toward us, low-angled; remarkably, there’s not a drop of sweat on her body. Shindō is telling us something. Later, one of Michiko’s friends describes Otoya as a “horrible and filthy person”—as if too much sweat is the external emanation of a person’s uneasy virtue; or a lack of it. The guilty Mr Nakanishi—dark-suited in the stuffy police interview room—pulls a handkerchief from his pocket and agitatedly dabs his neck. Guilt is a sweaty business. Later, he’ll be writhing from dope withdrawal, eyes dark and caved-in, on the island’s dead and dusty hillsides.

Elsewhere, Nagisa Ōshima’s The Catch instrumentalizes sweating as a kind of terror and fearfulness—and we watch how it streams over the anxious body of an unnamed, captured US airman (this is 1945, remember; the dog days of the Pacific war), who, played with intensity by Hugh Hurd (who’d go on to feature in Cassavetes’ Shadows in 1959), spends much of the film hobbled and chained in a musty outhouse, his wounds festering and his skin needled with moisture; even if Ōshima’s film lurches from dry heat to pouring summertime rain. Not too far away, on the horizon, Tokyo descends into chaos; eviscerated by firestorms and American bombs. Heat is calamity; it will swallow everything.

Kurosawa’s greatest radiator moment came with I Live in Fear (1955)—a tale of nuclear panic and family obligation. Kiichi Nakajima—played bug-eyed by an artificially-aged Toshiro Mifune—is the scion of a successful foundry business whose growing paranoia—he is suffocated by not unreasonable visions of the atom bomb—leads his coolly indifferent family to the brink of ruin. Nakajima begs them to leave Japan for the putative safety of Brazil—which he believes to be less threatened by the fallout that haunts his waking dreams. The family court deliberates over their misfortune; hearing both sides of the argument as they bathe in cloying heat and torrents of damp sweat. Fans are nervously handled, wet towels straddle shoulders, water is desperately downed. Here, Kurosawa’s sweat is the outpouring of sublimated terror—a kind of inescapable pressure that boxes them in from every side. When Kurosawa reached back into history, he became a winter poet; and it is lashing rain (Rashomon, 1950) and curling fog (Throne of Blood, 1957) that single out his histories. For Kurosawa, heat—and sweat—is a condition of a cruel and unkind modernity.

But let’s not also forget Kurosawa’s earlier Stray Dog (1949)—where a cop’s hunt for his stolen gun leads our protagonist, played upright and earnest by a young Toshiro Mifune, on a long, dark journey into the pulsating night of Tokyo’s underground. Through a series of sweaty, too-hot rooms, Murakami—Mifune’s cop—gets the measure of brothel madames, nightclub proprietors, amoral gangsters, and dope fiends—and their fixers. The effect is dizzying; of moist, heavy hands pressing through bodies—with sweat pouring liberally from every available orifice. Jazz—so “American”, so angsty and easy—is the soundtrack; offering a buzzing, discordant cool that nips and bites at Mifune’s scurrying heels.

For Kurosawa, it’s a matter of tightly-cropped faces—hair mussed up and messy—where beads and slithers of sweat are picked out by hot tungsten bulbs. He also packs bodies tightly when he wants to juice up the flossy intensity; in clammy bars, sardine-packed trams, and sticky police offices. Fans whirr, shoulders slump. The world is pressing heavily together.

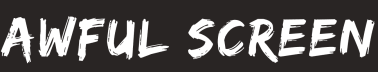

Elsewhere, in another of Japan’s great “golden age” heaters, we have Mikio Naruse’s Floating Clouds (1955). Yukiko and Kengo—doomed lovers who first hooked up in the dying days of Japan’s fated war in French Indochina—try to make things work in the ruins of postwar Tokyo. The city is cold; and the heat of their affair, which took place in the tropics, represents a kind of throttling death that cannot but catch up with them—even if Kengo remarks on the comparative coolness of their native city. In flashback, things are torrid; in shirtsleeves, these wartime foresters idle around in high-ceilinged, palatial rooms and dark hotel bedrooms; with the heat intensifying their steamy attractions and their bodies cut apart by shadows from slatted window shutters.

Naruse is explicit about the sordid intensities of this creeping heat. Yukiko’s death—like so many of these films, death is a “known unknown”—comes once they’ve beaten a retreat to the tropics of Yakushima island, where the humid climate decimates her already shaky health. In this instance, sweat isn’t only an intimation of guilt or shame, but a thing that will, quite literally, end your life. There is no escape; no easy way out; except through death, and the film’s postscript—a lick of vertical poetry—tells us that blossoms only bloom for a little while, and we must appreciate their beauty before it fades. Here, he’s admonishing the womanizing, doom-pilled ways of Kengo; but he’s also addressing us. History jogs, catching up with us; by the time it passes, we are already feeding the flowers.

Here, it’s hard not to think of W.G. Sebald’s invocation of the sublimated cultural amnesia that clogged up postwar Germany; where the “regulation of intimate feelings” that any propagandized epoch heralds crashes down into the “deficiency” of the public record along with the regime that authored it. The horrors are repressed; the destruction is absorbed. This isn’t to say that these things can be suppressed indefinitely; and, in the Japanese context, we can see the reckoning bubbling back—lives lost, cities ruined, acts that were done that now cannot be undone—through a “golden age” of cinema in which the past makes itself known not as fact (for nobody says it “outright”), but as a nervous, sickly sweating. Truth, and history, are rendered as moisture. It is rot; and it seeps into everything.

I’m trying to avoid the inertia of listicles, but “sweat” is so pervasive a symbol that it comes up thick and fast. There’s Yoshitarō Nomura’s Stakeout (1958), where —again—we spend time pressed up against roomfuls of perspiring cops, or Kon Ichikawa’s Heat and Mud (1950), which pulses with the anxiety and desperation that this era’s cinema so greedily fed on, or his later Conflagration (1958)—where an act of arson becomes a defiant symbol of postwar rebellion. Burning things, burning up, burning out; it’s all up for (sweaty) grabs.

For Japan’s listless postwar youth, meanwhile—those who didn’t fight, and had perhaps only the haziest memories of the war—steam, sun, and sweat acquired a palpable significance of their own. The epoch of taiyozoku—the so-called “sun tribe” subculture (affluent, hedonistic, lost)—typified a generation who rebelled against the stiff expectations of their parents and embraced the kinds of pouting promiscuity that would re-arrange Japanese cinema and society through the 1950s. Takumi Furukawa’s Season of the Sun—released in 1956—was the first, and schlockiest, of these stories, raising eyebrows and disavowals when it landed on Japanese screens just a decade and pocket change after the end of WWII.

That’s the history, at least; the actual film, lopsided as it is, turned heat and sweat into a nihilistic totem; opening with an upclose shot of bubbling, steaming foam that, within moments, ricochets through cards, jibes, and the boxing ring—with all the busted eyes, swollen lips, and sweat-rimmed faces you’d expect. Probably ham-fisted how Furukawa makes every effort to establish the kids’ rebelliousness; dropping references to whisky tabs, gambling debts, and how small of a fig they give for their mandated studies (English just isn’t their “thing”). Either way, “they do what they like”; even while admitting that they couldn’t conjure up a tear if they tried. But they can sweat.

It would fall to Kō Nakahira, and his Crazed Fruit, to properly splay out the aesthetic credentials of the taiyozoku. His 1956 program film (care of Japan’s long-in-the-tooth Nikkatsu studio) has all the roughly-hewn and scandalously too-cool energy of Japan’s newly doomed youth. Its story is one of frustration, liberation, narcissism, and nihilism—and the American-style bars and bourgeois villas that these seemingly unparented kids spend the movie haunting. Nagisa Ōshima saw it as epochal, how “in the sound of the girl’s skirt being ripped [...] sensitive people could hear the wails of a new age in Japanese cinema”. But here’s the (interpretive) rub: the scene in question (it’s a pivotal moment; one that seals two deaths) doesn’t feature the sound of a ripped skirt, but only the image of it—and Nakahira’s camera is already panning away. Ōshima had heard the tear, but he hadn’t listened to it.

Yet again, it’s all sweat, spray, and libidinal energy; and, like Furokawa’s film, we’re invited to ogle, to raise our eyebrows, but also to enjoy the vicarious pleasures. This isn’t quite a disavowal. Even then, the film was sufficiently scandalising to give the Japan Film Censor board a headache—and no small amount of clamour from housewives and conservative politicians. The youth are running wild!

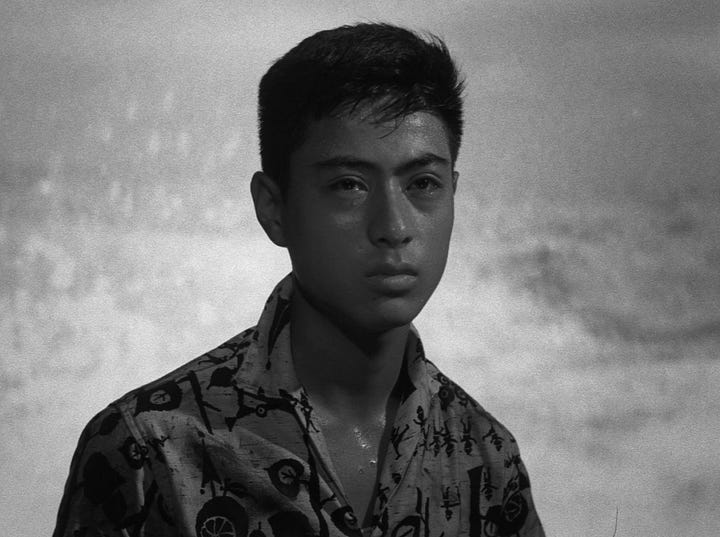

Crazed Fruit—like Season of the Sun—opens with the ocean and the misty spray of a motorboat’s engine, pompy jazz, and a slow zoom on Haruji’s staring face; revealing thick beads of sweat limning his forehead. From here, everything moves thick and fast; with boys shoving-racing their way through a commuter station in sunglasses and loose summer shirts. “Man, it’s hot”—the first words of the film, spoken by Haruji while mopping the sweat from his neck with a de rigeur white handkerchief. Listless teens, roving eyes, card games, and boozing glide along with Shigeyoshi Mine’s luminous, light-as-a-feather cinematography; all without a murk of the chiaroscuro you’d get from the latter New Wave or Kurosawa’s moodier, muddier samurai tales. The sun is shining; the days are long; but—as one of Haru’s listless friends observes—“it’s a wasteland for the young”.

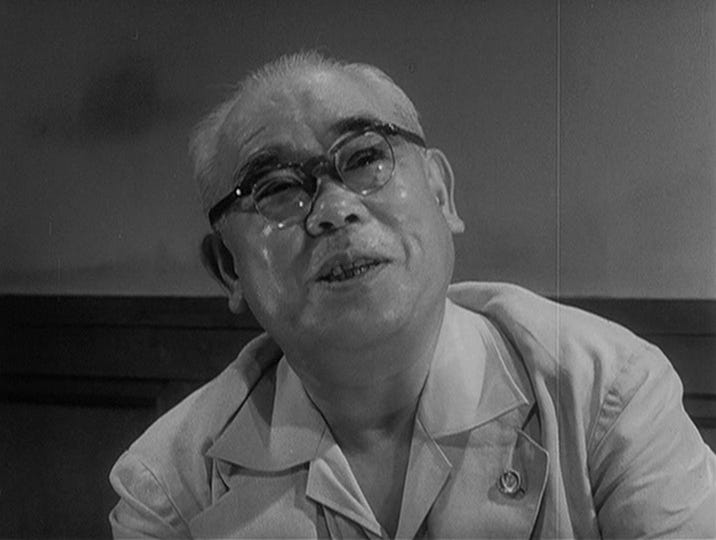

For the parents, all they can do is frown and sigh; declaiming against the “rude and raucous” lads to whom their children are in thrall. But something much more powerful than parental disapproval is at work here; not least a lot of ungrounded libidinal energy. In one memorable scene, we see Haru and Eri splayed out in their bathing costumes on the cliffs of the ocean; the scene intercuts between clenched hands, curling feet, bitten lips, and the sea’s rhythmic swelling. Nakahira doesn’t need to say what’s passing electrically between them. Later, drying her hair, Eri remarks—noncommittally—how she’s “worked up a sweat”. No kidding.

Later, when Natsuhisa—the duplicitous brother—grapples with his own conscience about two-timing with Haruji’s love interest (Eri, of course), his shirt is open, holding an electric fan to his face, his brow beading with sweat. The guilt bears down on him; but it isn’t enough to make him relent—despite lugging his heat-heavy body from sofa to fishtank to table. Their narcissism, boredom, and seemingly endless free time make work for some very devilish hands. They just can’t help themselves.

Even then, and as Chuck Stephens is quick to point out in his Criterion piece, the easygoing narcissism of the taiyozoku films was “outrageously oversize” and “scarcely the sort of lifestyle and luxury available to Japanese teenagers at large”. The cars, the cash, the lack of parental oversight or rules were a bourgeois phantom that didn’t really exist outside of the experience of a handful of properly haute kids. The grittier, more trembling genre movies of the 1950s came closer to the struggling reality of everyday life. It’s Michiko and Otoya who feel more alive than the bar-hopping, girl-swapping shenanigans of Haru and Tatsuya but, taken together, they signal the secrets, crises, and social anxieties that were pulling Japan in any number of dizzying directions.

Through this, it should come as no surprise that the film studios—diversifying from the mergers and extremities of wartime—sought to anatomize the changes that were perforating Japan during the 1950s; even if their political motivations remained obstinately cloudy—unless it was just about making a quick, controversial buck. Toho, Daiei, Shochiku, Nikkatsu, and Toei would compete to tell the story of postwar Japan; released, in 1952, from the confines and restrictions imposed by the occupying American forces. The centre—of course—could not hold, and many of the protean and sort-of New Wave’s most agitational directors would split off from the often rigid, industrially prolific studio system. Seijun Suzuki was ousted from Nikkatsu in 1968—and Shindō, much earlier—in 1950—had struck off to found Kindai Eiga Kyōkai. For these filmmakers, it wasn’t enough to eyeball sociological decadence and decay from the commanding heights of the big film industry, but to muck around with motor oil, hair cream, bodies, and—yes—sweat for themselves. The cinema would also undergo its own hot-under-the-collar rebellion.

For filmmakers like Masumura Yasuzō, this new age needed a new cinema that would “blast spectators out of their comfortable orbit” (in Michael Raine’s words); foregoing the naturalist “passivity” of the old masters. Sweat, in their hands, and through to the increasingly daring films of the 1960s, would lubricate a more sensationalist cinema that was just making itself felt. Yasuzo’s own films threw caution to the wind and went instead for much more muchness—namely, a kind of speed that would do away with the “pre-modern” tendencies, and sensibilities, of the old world. He meant this literally; because his cinema was faster, more propulsive—and it began to shake things loose. Kisses (1957) came first; Giants and Toys (1958), with its satirical send-up of an increasingly consumerist, individuated society, would properly blow away the cobwebs—and this time in colour.

I’ve said a lot, but this might be the “big sweat” in brief: in the cinema of 1950s Japan, sweat—and heat—symbolized a new decadence and uneasiness in a society that was struggling to assert itself in the now (mostly) smoothed-over ruins of a devastating defeat. There is a sensuousness to all this sweating; a veritable pathetic fallacy that pushes youth, salarymen, cops, and housewives into “rumpled” outfits “drenched with sweat” (Catherine Russell’s treatment of classical Japanese cinema is quick to pick up the allegorical quality of all this inclement weather).

Even then, sweat is also a kind of humanist invitation to show a little sympathy for the “too hot to handle” conditions that all these ordinary people are muddling through. We need only think of the beatifically sweating faces of the aging parents in Yasujirō Ozu’s Tokyo Story (1953)—or the sleepless, guilty, heat-wracked bodies of Kurosawa’s The Bad Sleep Well (1960); whose corrupt pawns, Wada and Nishi, are driven to madness and suicide in a web of unbridled corporate corruption in which they themselves played a pathetic part. When Season of the Sun’s Tatsuya hurls a candle at Eiko’s memorial (she has died while aborting their baby), smashing the frame, the family look up not so much in anger as incomprehension. “None of you understand” Tatsuya wails in the oft-repeated mantra of teenage anxiety. The social fabric was tearing apart.

By way of an historic counterpoint—an earlier and different treatment of heat—I’m minded to think of Tomu Uchida’s Sweat (1929), in which a wealthy lord, Kitayama Heizaemon, escapes the listless boredom of his estate and his toadying retainers only to find meaning among a group of labourers who are engaged in building his own mausoleum. Here, the “sweat” is that which he wipes from his working brow—a return to honest work and existential purpose. By the 1950s, sweat had become less of an honourable outpouring than a spiritual malaise; greasing the wheels of the newly emergent New Wave. It wouldn’t be too long before we hit the fantasies and phantasms of Teshigahara’s Woman in the Dunes (1965) or Shindō’s Onibaba (1964); when, heat or no heat, a properly modernist torture would make itself felt.