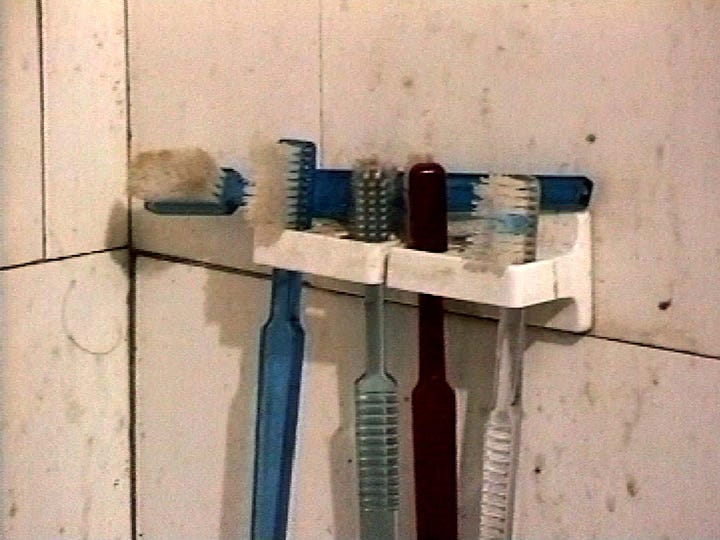

John Smith wants you to look at his toilet bowl, even if he remains teasingly indifferent to the shabby condition that his lavatory is actually in. With John Smith, we look at a thing in order to look through it; bending right back on ourselves like a convex mirror. That is to say, Smith is filming a toilet bowl; but he is also filming the act of filming, and we’re invited to consider both things at the same time; as if they are suspended in some kind of ontological soup. The film I’m referring to here is Home Suite (1994), which is often described as Smith’s “feature” film — largely by dint of it being much, much longer than his other films, which are typically quite short.

On Sunday, as part of London’s new-ish Slow Film Festival, John Smith invited me — and a group of about thirty other walkers — to look at his toilet bowl; only this time the toilet bowl — and the house that contained it — no longer exists; having been demolished in the construction of the M11 “Link” road; being a fact that Home Suite set out to document, albeit indirectly; skirting around things until, well, they couldn’t be skirted around. Because, in the film, John Smith walked directly into them.

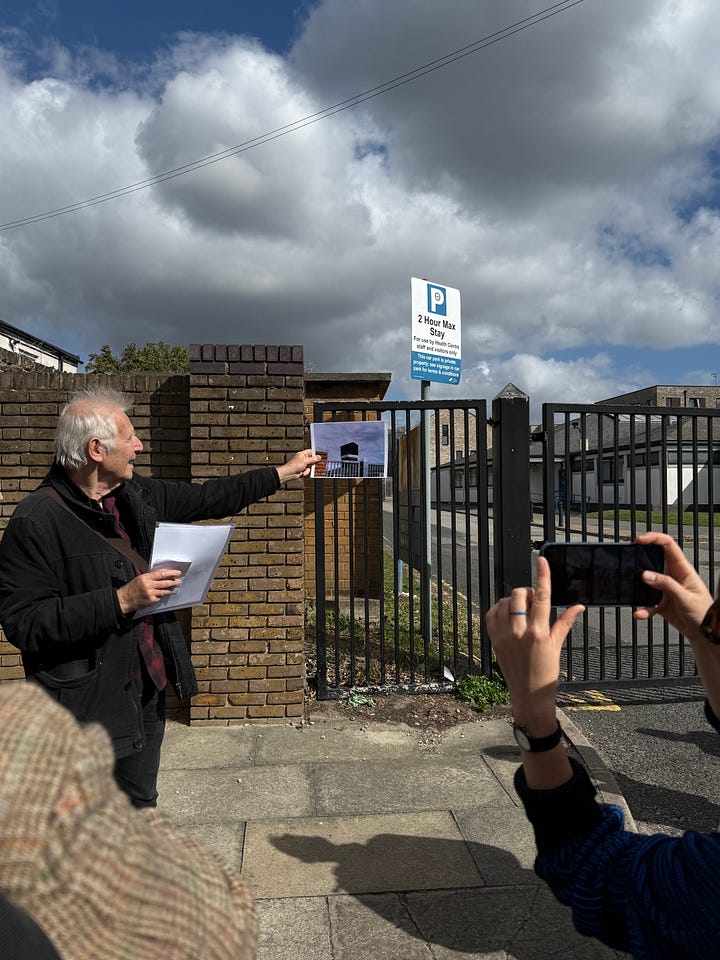

With John Smith as our master of ceremonies, we gathered against a tallish brick wall behind which could be heard the dismal droning of the motorway-that-is-not-a-motorway while John asked us to imagine the spectral memory of his house hovering in space, a little way over there — to our left.

Because we’ve seen Home Suite, we can picture it hovering there alongside him, even if the nature of our relationship to the ghost-house is different from John Smith’s own (because he lived there and actually stepped inside of it and slept there and ate breakfast there, and so on). Film — we’re reminded — is a memory device; but the nature of these memories is rarely direct. Things, for John Smith, are not what they seem; even if they are definitely still “themselves”. The toilet bowl is still a toilet bowl. To prove the point, John Smith pulls the chain; soaking himself in the process.

In many and multiple films, John Smith invites us to look at and think about places of habitation. In 1976, that started with a Dalston street quite near another of his former houses (The Girl Chewing Gum); in 1977, he showed us Hackney Marshes; in 1987, he gave us The Black Tower; in 1994 we had Home Suite and in 1996 we had Blight; between 2001 and 2007, he gave us an episodic film series called Hotel Diaries. Many of these films show us places John Smith has either lived in or lived near, be it for a long time or for brief durations. He has said that he wants to make films that are “as simple as possible”, and — to a large extent — this self assessment holds water: his films often are very simple in their conceit and devices. But that simplicity often evolves toward some kind of visual or interpretive “trick”. Famously, The Girl Chewing Gum proposed that the street scene playing out before us was being directed by John Smith — his voiceover bellowing out instructions seconds before the “actors” on screen ‘performed’ those actions. Its unsimple simplicity has always reminded me of the unsimple simplicity of Hollis Frampton’s (nostalgia) of 1971 — where the voiceover describes a series of photographs placed on a heating element, which burn and crisp up into black ash. In that film, Frampton is actually describing the photo we’re about to see; not the photograph we’re currently looking at. Like John Smith, Frampton was interested in displacement.

Later, we followed John across an elevated bridge which spans the M11; where he raised his voice above the din and asked us again to picture the house floating above the road while cars and taxis and lorries shuttled through it — creating and destroying the illusion in the same moment. Later again, drawing a plastic folder out of his bag, he showed us a photo of the Black Tower — or, a still frame taken from The Black Tower — and asked us to visualize where the actual black tower, which has subsequently been demolished, once stood. At that moment, we inhabited a kind of live-action postscript to the film he made in 1987. The displacement is complete.

Why does “home” matter? John Smith has often said that he gets most of his ideas from the spaces immediately around him. For many years, these spaces were neatly bounded by the largely residential roads of Leytonstone — an area of East London that, for a period in the 1970s and 1980s, became the locus for a thriving art scene of which he was but one prominent participant. I am sure there are still artists in Leytonstone; as far as I know, John Smith still lives quite close. Displacement is never total; it leaves a lot of things behind.

It’s why I believe that towers and other kinds of “tall” things feature so prominently in John Smith’s films; they are impossible not to see as we go about our lives. The tower blocks he plays with in Hackney Marshes loom up from the fields and cannot but draw our eyes and attention; he cuts rapidly between them, adjusting the angle to discover matches and disjunctions between each adjoining image. The same logic held sway in The Black Tower, where we see the unavoidably dense stab of blackness from many alliterating angles — showing us both how the view changes and how it remains the same. It might be a kind of pattern recognition; or pattern misrecognition; or it could be both things at the same time.

In this way, John Smith’s films remind us what cameras are — devices to record ‘stuff’ that we can see with our eyes — and what film ‘does’ to this stuff, which is to discombobulate the ‘real’ in ways that question the act of recording (and seeing) itself. We’re reminded that looking at something through a camera is an act of mediation; we abandon our ‘actual’ eyes the second we see an object conveyed to us through a lens. The filmmaker has got in the way; and that’s the point.

During Home Suite, we get a lot of Smith’s interstitial commentary as he handles the camera; pulling focus, shifting to macro, zooming, adjusting the exposure — reminding us of the very physical act of holding a camera and the kind of ‘finger work’ it requires us to perform as filmmakers. Typically, in the “big” cinema, these kinds of operations are hidden away through layers of slickly professional manipulation; with this film, everything is dragged out into the open. To put it another way, we’re reminded that film is also a verb; and in showing us that film is a “thing we do” — as it were — he displaces displacement itself. Clever, that.

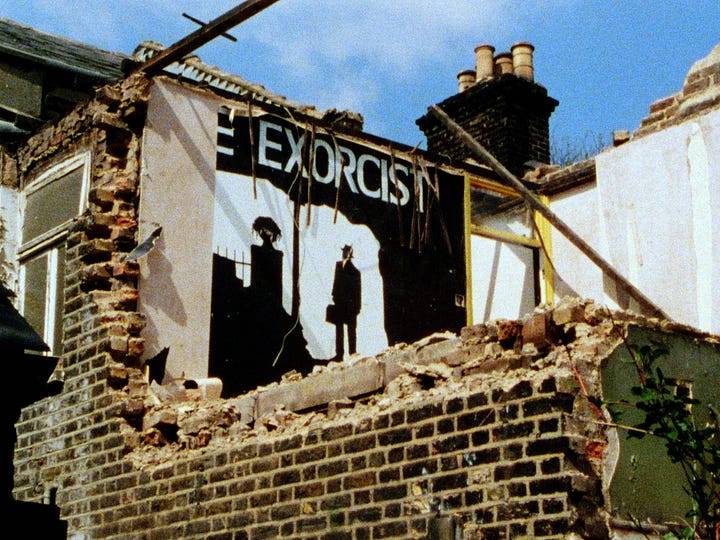

During our walk, John mentioned yet another example of ‘displacement’; telling us how the idea behind The Waste Land (1999) came from a toilet sign he’d seen in reverse — reading it as a kind-of anagram for T.S. Eliot. So, he filmed a scene in a pub’s lavatory that was also a meditation on Eliot and on the correspondences and confusions that bubble up between words, images, and things. Naturally, he shot this film in his (then) local boozer; when he mentioned this, we were standing a few yards from its front door. In Blight (1994-96), we witness the demolition of one of the houses along John’s street; where each shove and hammer-blow reveals another bit of sky or another bit of disemboweled domestic intimacy. One such shot reveals a poster for The Exorcist; during our walk, John wondered if the M11 link road — and the demolition that preceded it —was really a kind of "exoticism" of the street and the people who lived there. Here’s another example of displacement serving as a kind of meaning-making.

What I’ve always loved about John Smith’s cinema is its sense of humour, its honesty, its impish dishonesty, and its smartness; where each of his films give us a lesson in what cameras do and how film shapes and reshapes our world (and our memories of the world). Elsewhere — I can’t recall exactly where — I remember that John described his films as being about “loss” as well as memory, and while this is necessarily quite sombre, his films never gyrate toward morbidity; they are kind to us as viewers — bringing us in and making us a cup of tea rather than locking us out behind walls of abstruse complexity. In Home Suite, he does this quite literally.