MILK WITH GRENADINE

Out 1 – Jacques Rivette & Suzanne Schiffman (1971)

Black mask, loaded gun, shrill harmonica, secret letter, missing person, roving bust, glass of grenadine, pack of cigarettes, wheelbarrow, tortoise, a slip of blue paper, copy of Balzac, folded newspaper, flute, pale biscuit (broken in half). You can write lists of things that appear in Out 1—Jacques Rivette’s monolithic, 13-hour masterpiece, co-directed with Suzanne Schiffman—as if they were pieces on a chess board; and this is what Rivette invites us to do, even if he suggests that we might be distracting ourselves with so many herrings and canards (red or otherwise).

We might also list people; whom we might properly think of as “characters” (even if the film had no meaningful script and many of its performers were encouraged to improvise their roles during the two-or-so weeks it took to shoot). Naturally, these same characters are often playing other characters in turn; one of them (Colin) plays a mute (he is not mute; or perhaps he later regains his power of speech [Rivette doesn’t resolve this; it doesn’t matter]). You can also enumerate all of these things (things, people) until you reach variations of “13”, which is the number that Rivette exaggeratedly folds into the pastry of Out 1: it is a number we cannot ignore, though we will be given few tools—if any—to make sense of this number. It might be little more than a foliate fabrication (Eric Rohmer, who has a cameo in the film [as a literature professor], dismisses the suggestion; but isn’t he also playing a role)? Perhaps we should ignore his advice. The number 13—and the group who stand ‘behind’ it—might not matter at all.

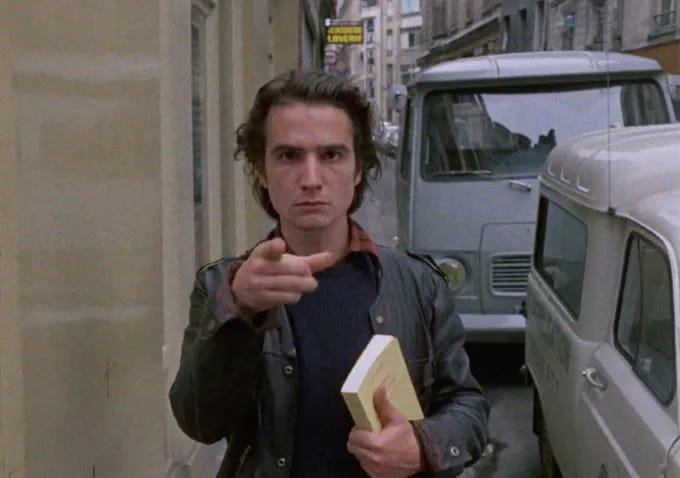

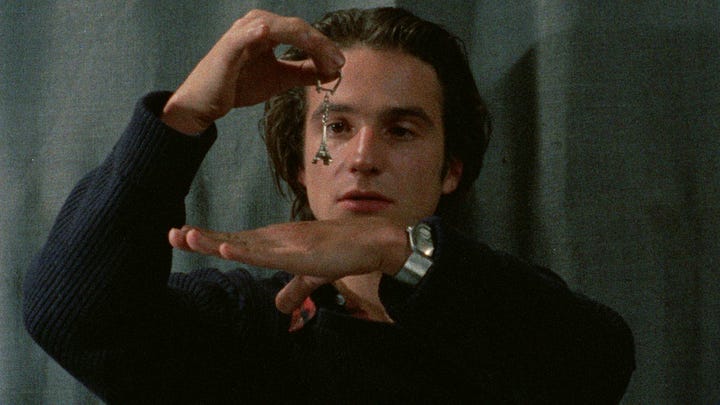

What is Out 1, actually? It’s the ‘story’ of two avant-garde theatre groups who are in the middle of rehearsing plays by Aeschylus (even if it’s unclear if the plays will ever be staged); it is also the story of Colin (Jean-Pierre Léaud) and Frédérique (Juliet Berto), who variously—albeit not in any obvious sense—become embroiled with these groups; it is also the story of another group—the “13”—which various members of these troupes may or may not be a part of. There are other figures, peripheral but important: a forlorn barfly lover; two men selling pornography in a cafe; a group of earnestly indecisive radicals set on publishing a newspaper (remember, this is not so long after the political convulsions of May 1968). We will not really learn who these people are, where they come from, what they ‘do’—or even what they ‘want’. Rivette positions us as a fly on the wall; we watch them going about their ‘days’ as if Out 1 were an ethnography of a bourgeois Parisian tribe (which I suppose it basically is).

More. Out 1 is indebted to but not an adaptation of Balzac’s La Comedie Humaine (1829-48), which doesn’t help us make sense of all this. Rivette doesn’t want it to; no more so than the tortoise should signify anything—or the glass of grenadine. You might think of Out 1 as a ‘thriller’ or a ‘mystery’, which would make it seem like you’re on the typically shape-shifting terrain of the Rivette we know. Rivette had planned for Out 1 to be broadcast on French television, which says a lot about public tastes in post-war France. It was ultimately rejected for this purpose by the broadcaster, which says a lot about public taste in post-war France. Balzac’s story is about a secret society known as “the thirteen”. Now we’re getting somewhere; or are we?

These characters, and these plots—which sometimes but not always and certainly not conclusively—get tangled together in ways that hint toward a kind of mystery and, in so doing, at least gesture toward the idea that Rivette’s film (like Balzac’s novel) is ‘saying something’ about French society; anatomizing its structures, poking around in its organs. But you really shouldn’t expect something as wryly propulsive as Celine and Julie go Boating (1977); nor as (abstrusely) signposted as Le Pont du Nord (1981). For much of the film, you’ll be doubting whether this ‘mystery’ is nothing more than a silly diversion dreamt up in Colin’s head; he certainly doesn’t tell us what he thinks—even when he ‘regains’ his power of speech. To what extent is all of this just an innocently extended daydream? Has Colin manifested the “13” into a kind of coherence? Out 1 was screened only once, contemporaneously—in Le Havre in 1971, though I’ve read that the projector gave out some way through and the screening was abandoned. It’s now having something of a renaissance, care of a (very rare) screening at the ICA earlier this year.

By way of getting something concrete down, we can say that Out 1 has a number of more easily identified and superficial themes (by which I mean, they are obviously ‘there’ in the surface of the film, even if they might not be all that instrumental in making actual sense of it):

Trickery and falsehoods

Improvisation (or the role of accident and chance)

Interpretation (of books, letters, patterns [substantiated or otherwise], &c)

(Literary and theatrical) adaptation

Anomie (though few characters will ever think of themselves as ‘outcast’ – or lonely)

Group social dynamics (sexual, interpersonal, whathaveyou)

Creative autonomy

Indecisiveness, inactivity, directionlessness

These superficial themes have a way of bootstrapping each other. Take Episode 4; Renaud—through the auspices of Arsenal—joins one of the theatrical troupes. He’s treated offhandedly, but is later invited to improvise with them. Lili gives him uncharacteristically harsh notes; she seems threatened by his presence; Quentin steps into the power vacuum to assert his own personal autonomy, but flails about and is misunderstood (to his chagrin). Renaud remains a somewhat distrusted outsider; Lili is proven right when, a little later, Renaud runs off with Quentin’s lottery winnings and the entire production falls apart. Here’s the risk of improvisation, the problems of literary adaptation, the power struggles within a group, and a mild dose of anomie. For Trickery you might look at any of Frederique’s scams and ruses intended to part people from their money (which are usually successful); for the complexities of interpretation, you have Colin’s attempts to decipher certain ambiguous letters that he receives and/or finds, even if it remains unclear who actually gave him these letters in the first place (I think it might be Pierre). Really, every turn in the film also features some degree of indecisiveness; whether that is a play which can’t find its creative direction or a group of writers who can’t get beyond the first hurdles of setting up their own newspaper, or a writer who—having sequestered themselves at the seaside—can’t get underway with their much-anticipated second novel. So, people drift, drink tea, smoke, scrabble around for cigarettes, chatter inconclusively, murmur, mumble, talk in loops and circles (oh! how they talk at cross-purposes). They are always loitering around or going somewhere else; the plot—which, thinking like a movie-goer, you might be feeling quite anxious to see get underway—slips and slides around the edges of all this stuff. It remains just out of sight.

In this light, you might say that Out 1—by turns—is frustrating, myopic, listless; just as it is also joyous, silly, magnetic. Even then, through this vapour of impatient patience, a ‘plot’ does begin to emerge, even if the terms of the plot—it is like a warped silhouette—are themselves unclear. What is at stake? Why does it matter? Rivette doesn’t lay his cards out; we are plonked, in media res, within a structure that is already incomprehensible to us. We find ourselves, like Colin, wandering from table to table—scene to scene—with our harmonica (our eyes; our ears) and our questions. Colin’s plot—or, the plot he attempts to sniff out— isn’t “our” plot; our plot is Rivette’s film, Out 1: it is the film itself.

Let’s put it another way: the film features two theatrical troupes and a secret society (which may or may not exist), but we might argue that there is actually a fourth such troupe; which is played by the audience. Like them, with their Aeschylus, we are attempting to iteratively flail our way toward an understanding of a text (Out 1), performing all sorts of hapless and at times incomprehensible gestures to ‘make it make sense’. I watched Out 1 at home and, like Colin, and Frédérique, and Thomas—I also found myself rolling around like a fool, rubbing my forehead, sometimes groaning, rolling my eyes, staring remorsefully at the floor, as if by re-positioning myself (literally) toward the film I might shake something loose, or at least stir my boredom. I am not being unduly critical of this film; the boredom is essential, just as it is enervating. You have to feel a little lost at sea; you have to want to be doing something else, somewhere else. Rivette longs his scenes out and then he cuts quickly; a sudden hot knife through liquefying butter. There’s a corrugated atonality to this; different parts of the whole operating along their own skittish rhythms. It means you get these sudden splurges of narrative development where you’ve all but given up ‘expecting’ it. He will keep you on your toes! When Frédérique reads the letters which, for the first time, reveal that there might be some kind of ‘plot’/mystery/secret faction (the “13”), she does so long after she’s stolen the letters in question; by this point we’ve half forgotten about them. Rivette distracts us with a long, plodding conversation in Pauline’s house; then he snaps back to Frédérique, dumping the whole mystery in our laps, sending up a flare about Pierre and Igor who, up until now, we’ve basically been ignoring any mention of. “Something is going on!”, we yell; “But I have no idea what it is”.

For the most part, but not entirely, Rivette keeps us cloyingly close to the action; supplying us with roving/mostly roving medium and close up shots that refuse to pull too far away. We are in an intermediary space, on the door’s proverbial edge, neither being kicked out or let in. The entire film is shot in scratchy, wishy-washy 16mm (a sensible cost-saving decision considering how much footage Rivette finally shot). Rarely, and—it seems—quite randomly, Rivette ‘rewards’ our desire for a more extreme closeup; just as he might ‘reward’ us with a balanced compositional frame (Leaud/Colin staring directly down the lens). But these moments are few and far between; there are more glasses of grenadine drunk and more cigarettes smoked than moments—across this monstrous 13-hour run-time —of ‘meaningful’ cathexis. “I don’t get it” mutters Frédérique, slumped against her tawdry bedroom wall. She is leafing through stolen correspondence; the shape of the “13”—we’ve been waiting a long time for this; four or five hours—begins to crumple toward us. The heightened intensity of the letters (shared between Pierre and Igor), the listless incomprehension of Frederique. “Not interesting”, she remarks; a pout. Rivette might agree: not interesting. We cut to Colin, pacing the streets of Paris, reciting Lewis Carroll’s The Hunting of the Snark (1876): “Two paths open up before you”. Which path are we going to take? We have no choice in the matter; Rivette asserts his own authorial eye, here;—and winks too, I think. Later, hour five or so, we meet Etienne; he is playing chess against himself. There’s Rivette’s wink again.

Out 1’s late-film preference for wides

What does Out 1 remind me of? I’ve seen suggestions that it’s a lot like Kieslowski’s Dekalog; perhaps because that great Polish masterwork was also shot for TV and shares a diverse cast. Really, Out 1 seems more akin to William Greaves’ Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: take one (1971) or Larry Gotheim’s Sorry / Hear Us (1986); both of which were experiments in collective, improvisational filmmaking and much more staunchly avant-garde in their ambitions (no shade on Kieslowski). In fact, Greaves’ film almost seems to share a (sub)title with Out 1, though it seems fittingly obvious that this must be no more than a peculiar coincidence. In both instances (Greaves and Rivette), there’s the insistence that the director is really not directing at all and has lost all semblance of control. Both films—in their own ways—push and yank and pull at the idea of authorship, even if their results are wildly different in form and affect. In all instances, we wonder whether what we’re seeing is arbitrary or the product of overarching control; finally, we realise we cannot actually know this for certain.

So, if there is a mystery, then we are being led along a path which Rivette and Suzanne Schiffman, his co-director, have decided to lead us, even if they can’t quite anticipate every furrow and pothole along the way. Yet, Rivette has set the whole thing in motion; he has produced the conditions in which the arbitrary and the unplanned can take root. Is this not Rivette’s reminder that film, notwithstanding certain modish ideas about the ‘death of the author’ (Barthes had written that essay in 1967, on the cusp of May ‘68), is a singular, coherent ‘thing’ that can, like so much jelly nailed to a wall, drag all kinds of fragmented miasma into its orbit—that he retains some kind of ultimate authorship over the film? ‘This is my pile of stuff’, he seems to be saying.

Right, we’ve already seen how, in Out 1, certain personalities—Thomas, Lili, and Quentin—are prickly and standoffish during rehearsals; Lili—who will be ousted from her group through her own frustrations—has particular reason to feel anxious about exerting authorial control. Thomas is guarded; drinking champagne at Emile/Pauline’s sizable apartment, he brings a gift of a tortoise for her daughter. Throughout, he refuses to say much about himself, demurring that he has no news to share; just as he refuses to give a copy of Aeschylus to Sarah, whom he had invited to Paris precisely in order to critique his production. Quentin becomes quite distraught—even if he plays it off—when his idea for a scene is misunderstood by the group; grasping his head, bulging his eyes – he cannot clearly articulate himself. There’s a very palpable fear of losing control, just as there’s a pervasive sense of indeterminacy—a refusal to commit. The author might not be ‘dead’—and their work(s) might certainly be their own—, but this isn’t to say that the author really benefits from this arrangement. For such an outwardly gentle film, there’s a discordant note of anxiety; the shape of something which we can glimpse yet which ultimately escapes us.

Yes, there will be violence (‘a girl and a gun’, as Godard might have it); there will be hysteria and burnt letters and secret rendezvous. But how much of this has anything to do with the ‘plot’—of the “13”—that Colin so relentlessly (albeit chaotically) pursues? Rivette refuses, for certain, to attribute any of the film’s sprawling fabula to any other part of the web; there is connective tissue everywhere, but none of it seems to connect. Rivette might be saying: it is easy to reify the unknown, but—in the process—might we end up disfiguring the known? It’s worth remembering that these kinds of interpretive clashes are hardwired into Rivette’s compositional method; having brought together a diverse cast of actors whose play-styles and preferences were already at odds, particularly when we consider that Rivette was shooting improvisationally and many of his actors would not have had a clear understanding of his final ambition. Here, the ‘plot’ is less important than the way in which his actors (Lonsdale, Leaud, Bertot, &c) react to and interpret the film of which they are nominally a part. To put it another way, as much as we find ourselves guessing into/toward the film, its actors are guessing right back at us.

But Out 1 isn’t much of nothing. There are—hours and hours along its course— the beginnings of everything becoming like so much sticky rice; forming into an amorphous, entangled mass. It is only with the arrival of part six that the grains seem to unstick themselves; the sudden murmurings of something that looks like a “plot”—an event, or a (dis)figured punctum. In part seven, Rivette withdraws his camera; and—for really the first time—we escape the too-tight embrace of his closeups and mediums in favour of cavernous wide shots stabbed into the meat of the film that occur almost (it seems) at random. As pieces of plot begin to winkingly announce themselves, Rivette’s camera—and Rivette himself—makes itself a little more absent; it also ends up looking a little like surveillance (the plotters and the detectives—if we might so lumpenly divide the film’s characters —being watched by other plotters and other detectives whose identities we cannot fathom). Now, we can begin to determine relationships (Thomas knows Pierre; Emile is hiding something from Sarah); the house in the Obade—which we had believed belonged to Sarah—now seems to belong to everyone and nobody in particular; and at which more and more characters—including those who had until now been peripheral—begin to congregate. The loose grains of sticky rice begin to clump together again; and chewed-over tropes (the White King, the Red Queen, the Prince, the Princess) are laid over the plot like a well-worn blanket, throwing us into even greater confusion. Now (aha, here’s a thing) Rivette reverses Beatrice’s dialogue while dropping metallic clangs and roaring aircraft into his sound mix. Approaching the crescendo, Rivette upends his tool box and lets all the pieces fly out. I’ve not mentioned the roving bust that seems to relocate itself autonomously from room to room in the seaside house (or is it many of the same statue; who can tell for sure).

Mulled wine, champagne, grenadine, whisky; Rivette’s characters—most of whom seem luxuriously unemployed—get through a quite heroic quantity of alcohol, just as they eat very little (except a basket of croissants and some rather plain-looking spaghetti). There is almost always a cigarette dangling from somebody’s fingertips. You also begin to note how some characters will cycle through a flurry of costume changes while others (Thomas, Colin) remain in the same outfit for (most of) the duration of the film’s running time. How many days have passed—is it not many weeks? Later, “weird noises”, ghosts, people hidden in rooms (maybe) – as if all the clandestine secrecies give way to actual hauntings. “Why weird?”, “I don’t know”. Leaud rings a bell, counts to thirteen; Thomas pretends to be sick. Emile and Beatrice affect a compromise; they were fighting the last time they were together, but Colin’s harmonica shrilly pipes over their scene; obscuring their dialogue. Now, Rivette holds even more things from us—the camera pans slowly away from them, peering not toward their bodies but the reflection of their bodies in the room’s tall mirror; Rivette cuts ‘randomly’ to frames of black leader; like the blinking of an eye. Throughout, the one person who might ‘solve’ all of this—Pierre—is nowhere to be seen. “What do you want to talk about?” (Emole). Finally, when there is a chance to talk—to say something – Emile refuses, clams up, demures. “Talk”. It’s been a long time since we’ve seen the theatrical groups at work; their projects have collapsed under the weight of something else; “stop asking me questions!” (Pauline/Emile). “Lie down and sleep; lie down” (Beatrice). Now, a great, sullen ferocity seeps into the film; a kind of jittery, unknowable madness. Colin rings his bell, counts to thirteen. “I’d like to leave” (Pauline/Emile). What begins with open, playful possibility ends in sullenness and finality—a needle that skips on the record. There is Pauline/Emile’s mise-en-abyme; a mirror reflecting into a mirror with her body trapped in the middle; she turns, confronting herself—turning her back on herself. The needle skips on the record.

If anything seems to fall out of Out 1, it would be the loneliness that comes with the failure of grand collective projects. Colin remains alone (returning to his harmonica); Frederique dies by gunshot; even Thomas—who has been at the centre of so much of the film—is left weeping on a beach, alone, before being given the ‘tidy’ narrative reprieve of walking into the sunset (even if he does so while bathetically fastening his belt). The “13” lament the disintegration of their project, too; whatever it is—or was. Through this, we cannot escape the temptation that all of this collective action—and its failure—says at least something about May 1968 and the concomitant hangover that its participants and fellow travelers later woke up to; echoing the same loss and ambiguity that undergirds Jean Eustache’s The Mother and the Whore (1973)—another lengthy film featuring Jean-Pierre Leaud. Eustache himself said that his subject was the “continuum of innocuous actions” without their being reduced to the “schematic abbreviation of cinematographic dramatization”. Like Rivette, he was trying to find a language of film away from film.

Questions. How much of Out 1 was fantasy? To what extent were its patterns and performances nothing more than the fabrications of two earnest, lonely ‘losers’? I can’t escape the image of Etienne’s laughing mouth; the disdain with which she treats both Colin and Frédérique—after all, she is the most buttoned-up and professional character in the film, either a symbol of the calculating business world or an icy insider who derides these outsiders from her ivory tower (you can’t sit with us). I can’t also escape the suggestion that “Pierre” is really a kind of euphemism for the director themselves; an all-seeing figurehead who directs the energies and actions of their followers while refusing to appear before them on screen, and to whom they’re all ultimately—and even fatally—subordinate to.