Hey waiter, there's a hair

. . . in my film gate.

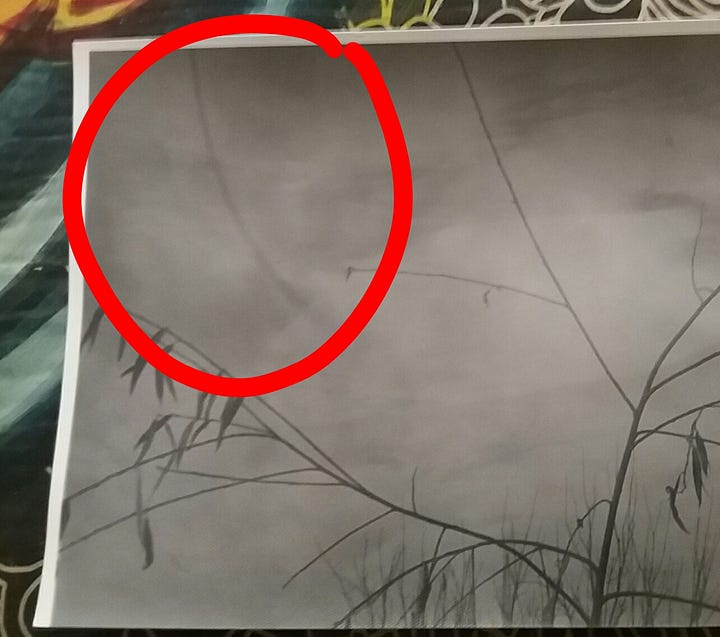

I imagine that the laboratory technician was tired, or merely unobservant; they hadn’t noticed that a small hair had wiggled its way into the film gate. You can’t blame them, really; there was so much work to get done. They were thinking about clocking off, a glass of beer, the rising hem of a skirt. It’s a very small hair; almost like an eyelash settling on your jacket. You don’t notice it; people say, “you have a hair”—they never finish the sentence. You have a hair—and then they remove the hair for you. “I didn’t notice it”; the film technician didn’t notice it. Either way, that hair—the hair “trapped” in the film gate—is now part of the film; it moves only a little, slowly snickering like an electric cable severed in a storm.

In the short-but-also-long history of film—when film was celluloid and nitrate and so much sticking plaster—many hairs worked their way into the film gate; and now we watch the hairs and, for the most part, disregard them. For a long time, before I learnt what film gates were, and how hair can work its way into the mechanism, I assumed that these fragile lines were cracks in the celluloid; that they were scratch marks or fissures of distress. But they don’t exactly have anything to do with the film itself; they are—I found this out later—one of those little things that can obscure or degrade a film.

It’s very early (for me); I’m drinking coffee from a disposable paper cup and listening to some jazz on the radio—I don’t know who’s playing. Actually I woke up because this hair in the gate forced me out of bed and carried me over here, to my computer, which is set up in another small room that, I think, the landlord had once intended as a dressing room. I keep my computer here and my desk and various bits of filmmaking equipment. There’s now an analogue camera—a Canon AE-1—and its presence reminds me of hairs that can interrupt films, just as ideas can interrupt sleep. I took 5mg of melatonin last night and all it gave me were memorably high-definition dreams; one of which startled me from sleep at the moment I first fell asleep.

The coffee reminds me of a piece of instructional-theoretical writing by Graeme Cole who, quite recently, wrote about filmic “shabbiness”; when I first read his piece I nodded along and said yes, this is it; that “shabbiness” is an attitude in film—a rekindling-re-aliving of film as a living material. Lens flare, he observes, “is the sun breaking the fourth wall”; it is, he continues, “cinema’s answer to guitar feedback”. The universe has its “untameability”; when we try to expunge light, or a speck of dust, or a fragment of hair from a film, we are trying to argue with the universe. Any victory we claim over it will be temporary and, I think, false.

But let’s go back. What exactly is a film gate—and what is a “hair”? Let’s answer the second question first, because its answer isn’t as obvious as it seems. Hair is hair (human, animal, whathaveyou), but it can also be a shorn-off piece of debris emanating from the celluloid itself. This is the stuff that gets trapped in the film gate. So maybe the “hair” is really a piece of the film after all; simply dislodged and pushed out of place. The hair—organic or chemical—might have worked its way into the film gate when the film was being shot; it might also have worked its way in there when the film was later being transferred for distribution.

When I was first studying at university, I remember a very early lecture in which we were introduced to the thinking of American anthropologist Mary Douglas; her thinking about “dirt”—which she was particularly animated by; enough to write a book about it—led her to observe that dirt is “matter out of place”. Look at it this way: we think nothing of brushing a piece of hair from our eyes or forehead (because it’s attached to us), but as soon as that same bit of hair falls into our sink, and becomes gooey and dark, we become revolted at the idea of touching it. The hair is now a residue; something polluted and unwholesome. Dirt, in Douglas’ figuration, is a definition that hinges on two very important conditions: (1) a set of ordered relations and (2) a contravention of that order. Hair on our heads; hair in our sinks. We might add to this—and Douglas didn’t write about film, as far as I know—that there is also hair in the film gate.

By “film gate” I mean the rectangular opening at the very front of a motion picture camera; this is where the light gets in—and it’s when hair and dust can get in, too. It’s the thing that filmmakers point at the object or subject they want to capture. This is a far easier definition to work with, as long as you don’t start thinking about the “gate” as a kind of mouth or even a kind of “wound”—an instance of the abject; something that can get sick or polluted or rotten. But it might just be these things.

The “hair in the gate” is trapped there and becomes part of the film; just as grain or areas of intense contrast or blotchy decay or light leaks become part of the film (Cole’s “untameability”). When we watch very old films—especially those that have been poorly preserved—we often encounter a thicket of noise; “stuff” has got in the way, and the image feels very far away from us. Hairs in the gate are almost inescapable; as soon as the lens cap was removed, it wasn’t just light that poured into the glistening void. Noise followed on its heels.

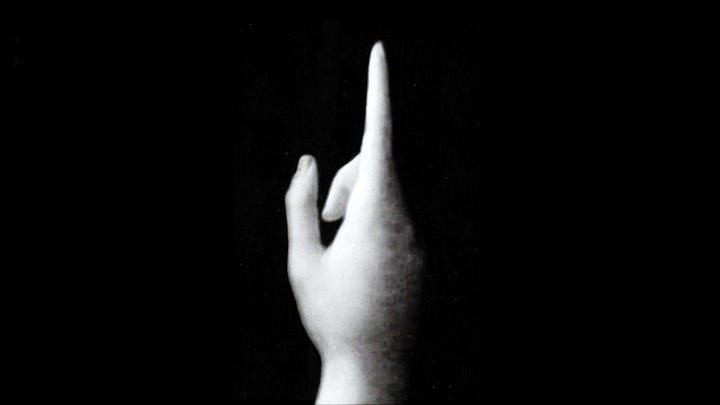

But if these hairs are mistakes, then the act of removing the lens cap was a mistake. I’m not particularly willing to agree to this. When we film stuff (telephone mast, flowering rose, stretching cat, the human hand), we open ourselves up to the possibility that errors might creep in; a hair might be the least of your problems. Things may, in the formulation of Douglas, come to be “out of place”; the hair—which once belonged to our heads, or to the celluloid itself—is now an anomaly, it no longer fits “a given set or series”. Now it belongs to film; purists say it shouldn’t be there. I say it should.

In The Image Book (2018), Jean-Luc Godard wanted to exhaust the image; to subject it to a battery of violences and disruptions—pulling and teasing it apart. He pushed his saturation to an obliterating maximum; he superimposed scenes like counterpoint, finding new harmonies in their now clattering arrangements; he piled on the contrast until shadows—once soft and supple—burned away into charcoal and emptiness. He was looking for something. He found hairs; they writhe around the screen just as he switches the aspect ratio—the presumptive coherence of the image (its formal cogency, its well-mannered framing, its delicate blocking) coming apart at the seams. “What’s left of the image now”, he asks. Funny but, despite all this so-called ugliness —you can clutch your pearls, at this point—he discovered that the images hadn’t lost their “aura”; they were still doing things—and he was still doing things with them. In The Image Book, Godard became wary of a thing called “beauty”; he found a sublimity in the mucky detritus of interruption. Hair today; hair tomorrow.

We will have to live with hairs trapped in gates; but, more than that, we should learn to love them. Film people talk about “bad transfers”; and this implies—to me—a “good” transfer, as if both categories are entirely obvious. But, what if they’re not obvious? Light has flowed into the aperture and barrelled down the lens and been thrown against the cell of film, where its image—in negative—has been inscribed. There were other things following on its heels; skin particles and beads of sweat and olfactory particles and, yes, fragments of hair. They all fell into the open void of the lens. If the camera operator was very astute there may have been opportunities to clear all this clutter out; but many were not—or it simply didn’t matter. Your “bad transfer” is the untameable; your “good” transfer is a pair of hygienic gloves.

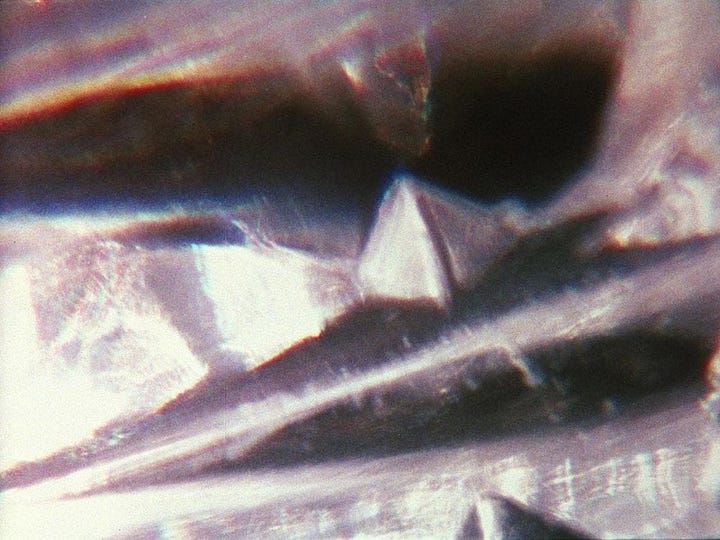

Earlier than Godard, Stan Brakhage had seen fit to mess around with film’s celluloid; he didn’t really care about purifying all these messy-mussy scratches or dust or leaks of light. In Mothlight (1963), he pasted bits of moth-wing and moth-body to his celluloid; its painterly-textural effect depends on its being anomalous. Later, he would hold a faceted glass ashtray in front of his camera (Text of Light, 1974), bending and distending the light; it was like an early diopter.

In The Dante Quartet (1987)—and many other films—Brakhage would paint and scratch and score directly onto the celluloid; in the process, he made it anomalous. Through his filmmaking, Brakhage wanted to uncover—or to rediscover—the “untutored eye”; to find, in film, something like the way we saw things before we knew what categories or series or sets were; before we’d brought the world under a kind of ocular order. His films, in Suranjan Ganguly’s words, “exalt human subjectivity”, and his scoring-scratching-disordering became a kind of “moving visual thinking”. Writing, in Metaphors on Vision (1963), Brakhage addressed the constrictions of filmic apparatus—he asked us to imagine “a world alive with incomprehensible objects and shimmering with an endless variety of movement and innumerable gradations of colour”. Incomprehensible objects = anomalous objects.

I think of him in his home-studio in Colorado, the late 1960s, the early 1970s; a mountain man who left the city of New York and went into the woods. He wanted to move away from the known of the metropolis and to discover (here’s the arch romantic) a kind of beginning; a perceptive disorder. There was a lot of snow, and earth, and leaves; the landscape changed with the seasons—things bore fruit and decayed; but they always decayed differently. He was in search of his own innocence.

Hair in the gate is a kind of innocence; its presence implies the persistence of an “untutored” eye—the detritus of the “deep” world having been flung back at us. For the film technician who ignored it, or didn’t notice it, the hair in the gate was an assertion of amateurism and clunkiness—it was evidence of the untameable world clawing its way back through the scientific-hypnagogic apparatus of cinema. Today, laboratory technicians and film preservationists spend a great deal of time cleaning old film; they remove hairs (where they can; even digitally “dissolving” them), they clean away noise, they scrape rot and mildew from the surface of film. They return cinema to its sets and orders and series; but all of these things are imposed—they assert that hair is anomalous and “out of place”. But what if it isn’t?

Years ago—I think it was in 2015 or 2016—I spent a long, disordered summer travelling along the heat-struck southern border of Turkey. Local news spoke warily of a “heat lens” that had formed over Iran, its frazzled edges stretching across the plains of Syria and into the busy, beetling towns of Turkey. I don’t know exactly when but, at some point, something in my left eye cracked; the first “floaters” in my vision formed. There’s only one or two or three of them; they swim like bits of hair across my vision, and I’m not always aware of their presence. When I think about them—like right now, for example, with my coffee and jazz radio—they reappear, swimming, like pond skaters, across the document I’m writing in. I’ve come to not really mind them. I don’t know if I can have them removed; I’ve never cared to find out.

If you liked this newsletter then please consider liking, sharing or subscribing. It’s lonely here.