Bricking it.

For a style that looms so grossly in the architectural imagination, Expressionism—which ran its course in Germany, the Netherlands, Austria, the Czech Republic and Denmark from around 1910 to 1930—has left us with a remarkably gentle footprint. A handful of photographs.[*] Plans (the pencil lines faded). A score of completed projects swallowed entirely by different aesthetics and emotions. Some things survived. Others were torn down, whether by accident or design.

In part, this lacuna rests on the violence and erasure experienced by wartime Germany and Poland; the immense churning up and obliteration of real materiel. The disintegration of cities. Of what W.G. Sebald called the “history of destruction.” Many things did not survive, or—if they did—then they are lumped blearily with the job of explaining to us (hungry and stupid for a quick fix) what Expressionism “is.” Buildings like the Chilehaus in Hamburg, which is trotted out with a sort of dull regularity whenever Expressionism is invoked. But the Chilehaus is but one building, and one whose acidic angularity—and jaunty confidence—aren’t necessarily the best representation of a much more unguent and, as I’m going to suggest, intimate architectural style. A style that was always performative, albeit in an alchemical way. A theatrical way. The Chilehaus is a house of ice. So let’s talk about the history of flowing and dirty water.

German expressionism and the neo-gothic underworld

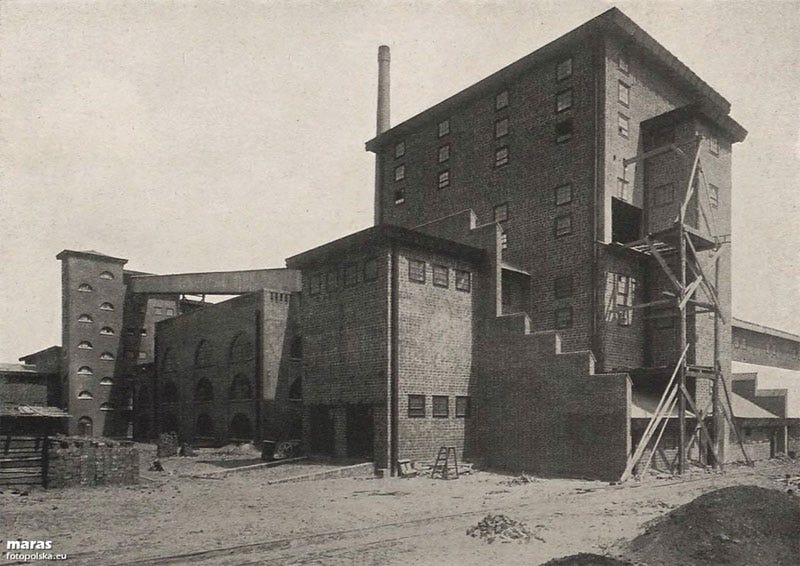

Until 1936—the year of his death—German architect, writer and designer Hans Poelzig would create some of central Europe’s most memorable Expressionist buildings. Teaching at the Breslau Art Academy until 1916, and again at the Technical Academy of Berlin until 1935, Poelzig’s Luboń chemical factory - one of his first completed major projects - does not betray the rotted, earthen texture of his most iconic work, the Grosses Schauspielhaus (1919), and for that reason might be overlooked.

But like all of his buildings, whether the bossy IG Farben building of 1928 or the Poznań Water Tower of 1911, the chemical factory was gaunt and gestural and heavy. A goliath, bathing in broken stone and old tree roots. These buildings were large and reared heavily into the metallic sky. They were functional. Modern but also hauntingly of the old world, gesturing not at the classical order but at a scourged, lapsed shadow of it. Not churches, but temples - monolithic places in the mountains where people were sacrificed to unnamed gods. It’s difficult to avoid sensationalism when talking about Expressionist architecture or to not dip your hand into dark waters when you do so. It is a mode of design that heightens the aura of the sublime and the proximity of the terrifying to it.

In her magisterial re-evaluation of cinematic Expressionism, Lotte Eisner remarked on the “reliance on formalized gesture,” the intimacy and use of dark staging and pooled light that had been translated from the theatre of Max Reinhardt and hammered out on the anvil of the films of Oscar Murnau and Fritz Laing. Films like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) or Faust (1926). And this is key; that Expressionism was, while dark, and ominous, also an expression of wild, romantic intimacy - and incredible fantasy.

Architecturally, we’ve often failed to reassess and consider the ways in which Expressionism did and did not overlap with the cinematic movement that also bears its name. Reinhardt’s Midsummer Night’s Dream came out in the same year as Lang’s Metropolis - both 1927. And both were stagey, dramatic and sepulchral, equally modern and cloyingly ancient in their evocation of the pagan blood temple. And yet, both expressionist theatre and architecture go back deeper than the days of expressionist film, into the days before even the Great War of 1914 - 1918.

But that is the subject of another post, one much longer and more involved - about the post-war German film industry, the rise of UfA and the creative outlets of the era’s architects. But this is a post about one particular architect and a specific building that was completed many years before - in the flat heat of the summer of 1911, and of how looking at this building—a factory—helps us to add nuance and texture to our understanding of what Expressionism was and what it wanted to be. Of what it wanted to manufacture - and the world it wanted to produce.

We’re talking about the Luboń Sulphuric Acid Factory, Poland.

A factory is a factory. Until it isn’t one.

A factory is not art. It is a site of production. The transformation of one material into another, through the action of human and mechanical intervention. Bodies work on metal, glass, leather and brick. The process is alchemical, and linked closely with the work of medieval magic. The airy factories of CIAM and international modernism were infinite in their transparency and aimed to literally embody the forms of the future. Buildings like the the 1930 Van Nelle Factory of Brinkman and Van der Vlugt, located along the Schie in Rotterdam, which Le Corbusier described as a “poem of steel and glass”.

The Van Nelle Factory, 1930In contrast, the Luboń Factory is holed-up, close to the ground, a brute. If it were a beast it would be dark, a stinking hog - ancient and powerful and incoherent. Its eyes are half-closed. Its exterior is jagged and not soft. If it is a factory then it is a factory having come into awareness of its purpose; to create a destructive, murderous chemical, aware that the acids created within its walls are capable of producing immense decay and suffering, or— at least—can and will lead to the transformation of the natural, organic world. The stuff in this building will fuck you up.

But then, this is intimacy; the conveying of a secret. A cthonic muttering, spoken in a secret language. And Poelzig knew this very well; a student of architecture and stage design both, he was well aware of architecture not simply being a container but a vehicle, a setting against which action unfolds. Its ziguratted, stepped massing; its half-closed eyes; and his gaunt walls of bare brick, add touches of the unreal and the folklorish to a space that, in 1911, could not have been more modern.

There is no correct way to make a factory, as long as its constituent and manufacturing components are properly installed - its functions protected. The factory is an oesophagus, stomach and gut. It is a sphincter. But as long as it is a system of organs and un-bodily functions, then the casing - the shell - can run to fat. In 1928, the Carreras Cigarette Factory—owned by the Carreras Tobacco Company—opened a vast new factory in the heart of London’s Mornington Crescent. Designed by Collins and Porri, this 550 ft. goliath was executed in the a la mode art deco style of its age, yet made sure that - despite these opulent stylings - it had the world’s most advanced air ventilation system and the most cutting edge filtration. The poisonous factory must necessarily be a healthy, sanitary facility. The bourgeois “battle against dirt” was, as Viktor Buchli describes in his Archaeology of Socialism, a war against the ills of the soiled past and an attempt to materially engineer a future society. The building was not, of course, concerned with the health of its workers - or its customers. Rather, its ambition was to interweave the crossed trajectories of productive architecture and material progress. More curiously still, the building made use of distinctive Egyptian-style ornamentation; including a solar disc dedicated to the sun-god Ra, and two gigantic black effigies of guardian cats. The architecture of the eternal godlike underworld was yoked to the motorcar of 20th-century progress.

“So what sort of factory is this?”[*]

At the time of the acid factory’s manufacture, Poelzig was engaged with developing a specific language for factory buildings, which he considered “the true monumental task of contemporary architecture.” Sinister and neo-Gothic, such monumental buildings were to express—simply and clearly—their immediate function, but also to express the transformation of which they were part.

In their Factories for the Future, Nevine Anous quotes Poelzig himself, pushing for a typology of manufacturing aesthetics that would directly reflect - and reproduce - the national state of mind. Easy to read, then: dramatic, energetic, vast and radical. But Anous also notes the similarity between contemporary cubism and the features of Luban; the irregular, slanted windows, and the attention paid to its geometric edge. Natasha Dhillon calls such places “space caves,” referring directly to Poelzig and his chemical factory [*] - and it would be important to note the failures of Poelzig’s approach or, at least, his interlaced intentions in this regard; that the factory, while being aggressively, dramatically “modern,” was also rooted in the prehistoric; in the violences of the underworld. Its “mass and acute angularity” was of the modern world, but it was not a product of it. Rather, the factory—alongside the acid it manufactured—expressed the opaque imaginary of the ancient, raw earth that would be needed to feed the modern. In the grizzly aftermath of the Great War, Poelzig would have understood just how closely linked the modern project was with old-fashioned earth, stone and death. Luban is the relay, the handover between the new and the old. As such, it could never be a palace of glass and steel. It had to be a gloomy and threatening grotto. The future would not be created, but angrily birthed.

For contemporary critics like Behne, the Expressionism of such architects as Bruno Taut and Hans Poelzig were representative of a new “Logical” architectural order, - without “any emotional ballast.”[*] But he was also moved to write that, with closer scrutiny, “their aesthetic appeal becomes ever more intense … purer and stronger” - “sprouting naturally from within.” And it’s true, Poelzig was seeking a way of disentangling architecture from easy emotions, and of matching the form with its function. The acid factory was - directly, and calmly - a factory. Eschewing ornamentation (and therefore echoing Loos’s war against decoration), his works expressed their meaning directly through their form.

This much is indisputable. But I would also be wary of claiming that the Luboń factory is un-emotional. Rather, its emotions run deep, and murkily; following a vein into cavernous prehistory. In this way, Luboń—and other early German experiments in Expressionism—could not have been further from the glassy developments of International Modernism, and never pretended to be. With structures like the acid factory, I find myself both comforted and unnerved. And perhaps this feeling would make Poelzig many things other than “a logician of architecture,” as Behne proposes. And even if Expressionism would not long after disappear, there’s an argument that it had to - so heavily bowed down was it with the terroir of the deep earth from which it came, and which would eventually consume it.