When the bombs finally fall, you will be standing at a sink—a suburban sink—rinsing a glass. You will be standing in line at a grocery store, blinking, retreating; the sudden snap of light that floods the distance with gold. You will be rolling a cigarette on the bank of a ford, the early morning mist, feeling the first touch of sun on your chest. It will be a hot day, this last day. You will be stuck in traffic, long past caring , hand switching the dial between the obnoxious tones of talk radio and the slow blood of Ravel, the keys falling like little pieces of glass. New Order. Blue Monday. You barely have time to open your mouth.

Or you will be floating on a hot-pink pool inflatable, one of those with a little niche to hold your glass. Frozen margarita (too much salt, and tacky in the mouth). Your sunglasses resting on the flaked red of your nose. Your thick midriff pale as mozzarella. Somewhere a radio is playing, though it is not a radio. Canned voice. Frank Sinatra. A stream of dust floats down from the ceiling. More than usual. The bulbs flicker, and correct themselves.

So that was it.

you’re in fucking hell.

***

In the summer of 1964, the millionaire owner and founder of Avon Cosmetics, Gerry B. '“Jerry” Henderson, broke ground on a luxurious bunker buried some 26ft beneath the ground, two miles east of the centre of the Las Vegas Strip.

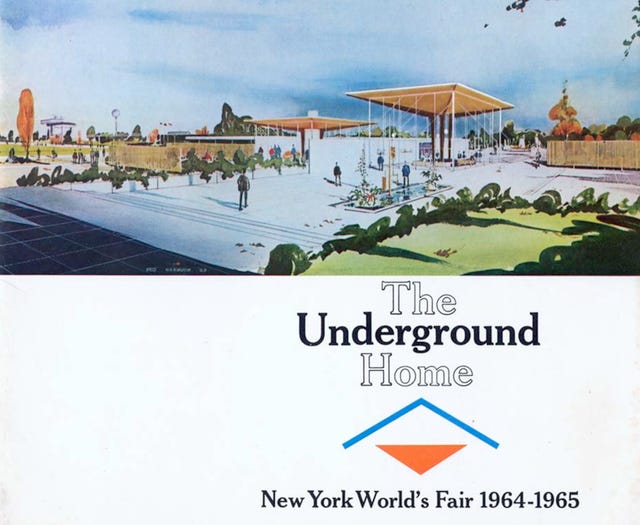

(a photograph of a bunker model built by the Swayze Brothers before the 1964 fair)

This palace of concrete and steel covers an area of some 14,620 sq ft and includes such amenities as an exterior yard, a guest house, trees, spa, BBQ, fountain and wall-to-ceiling murals of the surrounding mountains and forests. Forbes - unsurprisingly - seems impressed. It had one remarkable and singular purpose; to ensure the survival of its occupants through the eventuality of a nuclear strike during the most fervid and anxious days of the Cold War.

To put it another way, the bunker was designed as a living mausoleum against the world; a refuge, a fixation. In the cultural landscape of Cold War, red-lipped nuclear anxiety, Henderson was motivated by a particular fear of sudden and total ruination, having founded the “Underground World Homes” company in the early 1960s - exhibiting his ideas for post-nuclear survival at the New York World’s Fair. His presentation had been titled, “Why Live Underground?”.

And yet, “Jerry” Henderson’s fascination with the possibilities of subterranean living must not, however, be confused with the idea of sacred refugia or trembling angst. While mortified by the possibility of nuclear destruction, Henderson saw an opportunity for an entirely new way of living - one that would not only guarantee survival in the case of the H-bomb’s descent but would do so with great and modern comfort. The “Underground Home” was no sanctum, but rather an optimistic, techno-futurist wet dream spat into the ear of the existentially deranged United States of the mid to late 1960s.

Henderson’s ambitions were not isolated ones. His enterprise was supported by the efforts and financing of the Swayze Brothers, who would construct his own Las Vegas bunker. Henderson took a 51% stake in their construction business and worked closely with them in realizing the World Fair exhibition. Not long after the fair closed, the brothers walked away from this project altogether - realizing the prohibitive cost of constructing these homes at a profit. “We split up [because] there wasn’t enough market for the thing” explained Kenneth Swayze to the L.A. Times in 1996, adding "It was not a thing that we cared to pursue."

But old “Jerry” Henderson? He did care.

It’s why he moved into the bunker full time, living within its cloistered, pink-powder walls until his death in 1983 - seven years before the end of the Cold War. In some ways, he’d been a victim of it.

***

In a lecture given to students of the Graduate Writing Division of Columbia University on March 29, 1983, fantasist and writer Italo Calvino spoke frankly about the creation of his Invisible Cities, how it had been a work of cumulative free association, explaining: “In one file I collect[ed] pages on the towns and landscapes of my own life, and in another [i collected] imaginary cities, outside of space and time.” For “Jerry” Henderson, the landscapes of his own life were to become continuous with the landscapes of the post-nuclear, post-apocalyptic imaginary. The future was folded into the past, or - to put it another way - the imagined future became a real city (a real intervention) within the pre-nuclear present. The fear of total destruction - the event horizon - turned the past into stone.

During the early 90s, Ignasi Sola-Morales theorized the concept of terrain vague as a contemporary space that includes the marginal wastelands and vacant lots located beyond a city’s productive spaces, oversights in the landscape that are “mentally exterior in the physical interior of the city.” Caught between nature and artifice, the Las Vegas nuclear bunker occupies another, albeit similar genre of space; non-productive, yet removed from the exterior and interior alike. A subterranean, hidden place, the bunker - except to those who know of its whereabouts, and have access to its rooms - occupies a space outside of the sloppy, comingled penetrations of exterior-et-interior. It is not overlooked, disregarded or dismissed because it is not even perceived in the first instance. Non-productive, it has not even been removed from - or become a product of - the productive economy.

Perhaps this explains why its creator did not feel compelled to ape the functional, productive languages of conventional nuclear bunkers; the defensive architecture of Virilio’s second world war bunkers, or the militarized complexes that the government was steadily burrowing beneath the mountainous states of the Mid-West. Rather, Henderson sought to create an amplification of his already existing aesthetics of consumer excess. The bunker would not be a lesser version of his world, but a magnification of it; more audacious, more opulent, and less anchored to reality. Even while - at its heart - it remained a simulation of it. At the end of the world, all possibilities were rearranged. You can start again, in the mirror-hall of your dead life. Normal compositions ‘become strange,’ disfigured. Amplified, swollen and facsimiled, the Avon bunker-haus came to embody the toxic unease that was growing within the heart of post-war consumer capitalism, becoming - ultimately - a strange facsimile of it.

In other words, the apocalypse won’t set you free.

***

Lamps, lintels, drawers, television stands, toothbrush holders, cups, glasses, screws, shoe racks, door handles. The Las Vegas bunker leverages what came before, unable to escape it - all the while seeking ways in which to torment and make-strange the signifiers of an era defined by post-war consumer confidence and nuclear anxiety. Frankenstein, this is your monster; decked out in pink plush and marble finishings.

***

The invention of total destruction was also the invention of total survival, to bastardise the language of Paul Virilio. The hanging sword of nuclear death - on a vast and global scale - triggered an unequal effort to survive, and by any means possible. Nuclear bunkers - a cthonic, subterranean escape into the world’s mantle - are a category of defensive architecture which shares much with the cloister, the refuge, the silo, even if it is made stupid by its own inconceivability. A nuclear strike would blanket a country in cascading death. It is unlikely that the builders of such a place would have time to convey themselves to their place of retreat unless they already happened to be within it, or within moments of its welcoming doors. And who would willingly inhabit a place like this, far beneath the lace of cornfields and dry scrub above?

a mirror home beneath his home. In a photographic project exploring the cloying non-nuances of this indelicate place, Juno Calypso asked: what [is there] to do with a million years? pout sadly in mirrors. adhere to increasingly precise routines, orders, behaviours. or decay, lapsing into disorder - a riot of unchanged bedsheets, unwashed dressing gowns and the stubby tack of dropped cigarette ends. Either way, you will go to seed in this place.

Calypso’s series of photographs - dense, precise, longing, and flatly erotic.

The Avon apocalypse haus expresses the total inanity of wealth. It embodies a stance that is always already leaning toward isolation, sequestering, quarantine. In the mural found at the limit of Gladwell’s simulated villa, there is no sign of human life, activity or intervention. There is no infrastructure. No houses. No attributes of humanity. The possibility of total death - and the failure of the surface world above it - enabled Gladwell to envisage his own making-good of utopia; a private island shorn, irrevocably, from the human world, even if it was made possible by it.