Something a little different, for a change. Diversions via art, installation, horse-theory. Etc. Yet, still film(y).

— In 2015, Gavin Brown Gallery restaged one of Jannis Kounellis’s more beguiling arte povera installations — Untitled (12 horses). Within the large, air-conditioned space, twelve horses were tethered to the walls, the flooring beneath them a kind of “quieting, supple, rubberized” material, as described by (yes) Jerry Saltz. The conceit is very powerful, so far as it goes — these already ‘domesticated’ creatures, having been tethered in this cleansed and almost medical space (an anti-agrarianism), in turn radiating a kind of rough metaphysical aura.

— Their original staging (of 1969) must have felt perhaps more pointed – within the space of Rome’s Galleria L’attico. Polished shiny tiles, and the horses arranged in a kind of U-shape. The space was smaller; more cloister-like than Brown’s immense factory (it was actually a garage — an underground garage for cars). An unattributed quote describing that installation describes the absence of dirt, hay, straw, as if the signifiers of horsiness had been evacuated from the room, and all that was left (sans stench) was their physicality, their breathing, and the immense incorrectness of their being there. Kounellis referred to it as a kind of “stor[ed] silence, a vast absence”.

— The re-interpretation of the installation is worlds away. Kounellis was taking aim at the Vietnam War. She was also commenting – loosey goosey – at the rapid abandonment of the countryside that was taking place under rapid Italian industrialization. Brown’s 2012 (re)staging — in its more clinical setting; taking up more space, expanding the distance between each horse — speaks to a kind of acceleration effect. Even more horsiness (or, its accessorization — and its bowel movements) has been vacuumed away. But more is left over. Confusing, that. Defamiliarization, Etc.

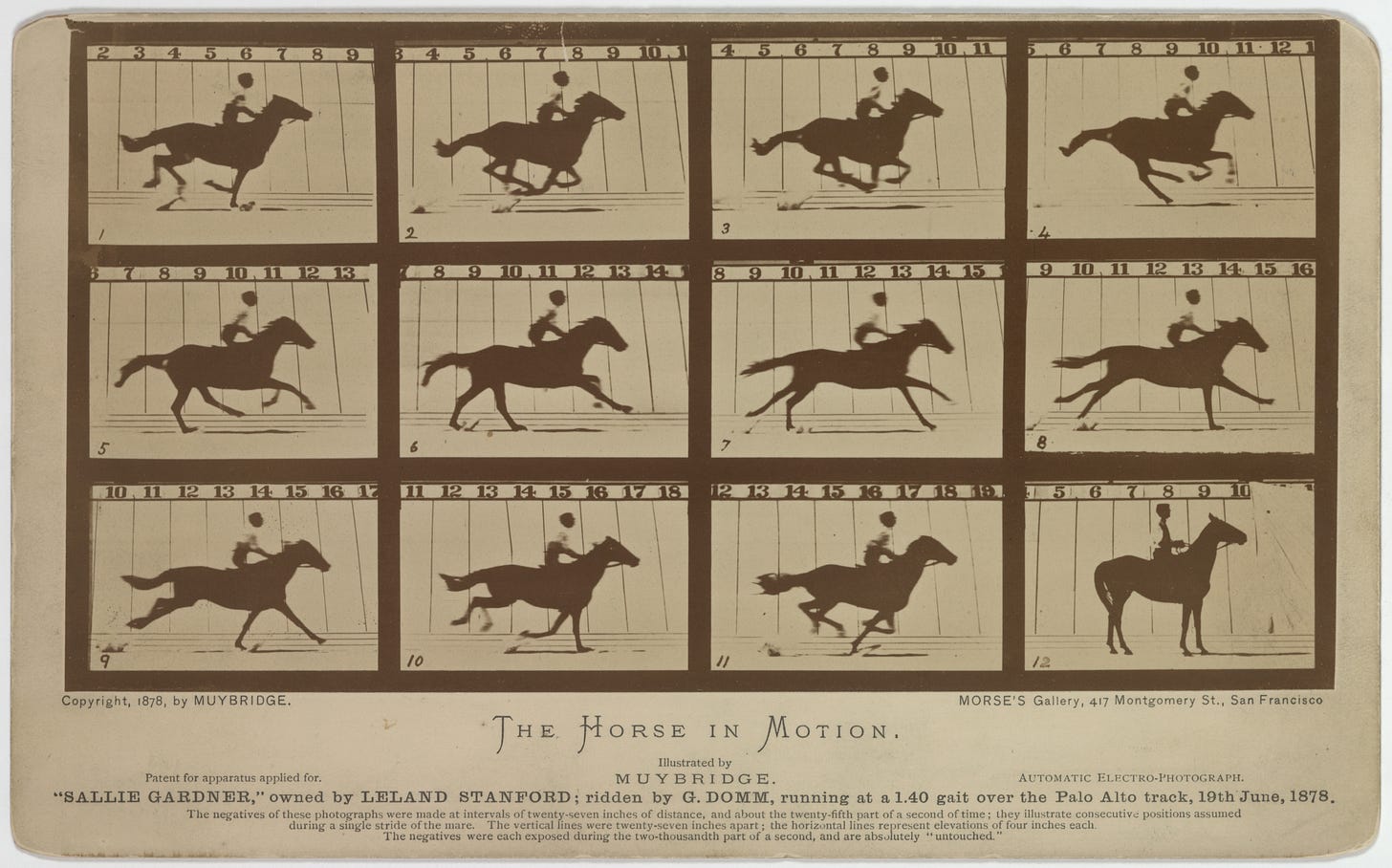

— Beasts of burden. It cannot be said that the horse — or its dejected xerox, the donkey — is in any sense a mere object of cinema (a more modern art than art). Really it is the subject, the star. Muybridge, in 1878, spent not a little of his fortune trying to film these creatures as they pelted their way up and down a specially prepared track in Palo Alto, California. The story of the first film is also the story of the first horse — a corrugation of jointed limbs and wire-hard hair. There was also a man, Domm, but his identity — and fate — is easily chucked in the memory-hole. What we learn is that the horse is what matters (bolting before carts; stable door split in two). Any number of early films made humanity as a whole its subject. Workers leaving a factory; crowds ogling a camera (throwing snowballs, smoking, leering). The horse is really the first movie star. We see it in all its grandeur — alone.

— Later, in 1888, Ottomar Anschutz would repeat Muybridge’s experiment — with more gusto, and greater clarity. For him, it was — properly — a film (Horse and Rider Jumping over an Obstacle). His horse would leap, and not merely (dis)locate from frame to frame. It should be remembered that Muybridge’s effort — that of the horse Sallie Gardner — is really a series of 24 photographs, in a motion that would constitute only a second of Godard’s film as “light moving at. . .”. You know the rest.

— The horse — more terrible and dangerous than the fumbling familiarity of man — is a creature we have bound to ourselves (domesticated; subjugated). It remains, still, beyond our easy control — and beyond our comprehension. Take, for example, Jerry Saltz’s loving fear of 2015. A single swift backwards kick and our brains are paste. Beautiful death.

— Francisco LaRubia-Prado argues that — when they appear fictively, in cultural products — horses “decisively contribute to expose, debunk, and rectify human mistakes or wrongheaded cultural practices”. These mute beasts are more like voids into which we pour all of our abjection and strife. Against them, we look either bad or good. Horses have always been film. Not just in film. They have shaped the technological structure of what film is (the capturing of individual slices of time that, once stitched together, plot an entire mechanical movement). Bresson’s Balthazar (really: Balthazar’s Balthazar) is passed around, escapes, flees, is subjugated and liberated. Shepherd’s gather around his body, closing in — his wound tragically visible.

— They are the heart and soul of continuity, which really lays the bedrock (or the stable straw, if you will) of film and what it is (and how, later, it has been disarticulated — messed around with). Hans Richter’s Race Symphony (1928) stands apart here, perhaps; neighing and whinnying. Even then, the emphasis is squarely on the social conundrum of the race as spectacle. Horses hardly get a shoe-in.

— Like Haley’s comet, Sally Gardiner (horse, remember) returns. Not often, but he does. For Bresson, there was Au Hasard Balthazar (1966). Later, Bela Tarr made The Turin Horse. Later still, only this year, in 2022, did Skolimowski make Eo. Each of these films centre a horse — or an ass, let’s be fair — in the centre of their narrative. They might not say anything, but their presence creates a certain “structure of feeling” — a sort of palpably allegorical angst about human nature. The helpless yet proud equine intelligence regards us with a kind of doubtful pity (we think, but we can’t know. Not for sure). You might say that the horse film is its own genre in a way that cannot be said of films about cats or bears or birds.

— Tarr’s Turin Horse is an expanded cinema that is really a sort of echo of Nietzsche’s descent into insanity (he saw a horse being whipped, and threw himself — weeping — onto its frothy neck). “Mother, ich bin dumm”, he said. Not really — you were merely being kind! Too late, too late. A pressaging of doom — really an eschatology; coming to terms with our own wracked obliteration. Turin Horse is properly Tarr’s most cynical and debased film. Earlier works were laced with moments of catatonic jouissance — the planetary dancing of Werckmeister harmoniak (2000), the drunken, lusty rabble-rousing in Satantango (1994). Here, we get a little flicker of fun — a troupe of so-called Gipsies who turn up in the far and middle distance, and who subsequently get shooed away. Tarr acknowledges the party. We’re told (finger-wagging) to stay at home. Horse. Horse comes and goes. She refuses her food and refuses to serve her masters. This presages their own entropic decline. ‘Stableman’s’ limp arm, their hot potato meals eaten without cutlery (jabbing at the starchy potato flesh, the girl not even lacing it with salt). The end is nigh. The apocalypse will not be seasoned!

— There are thirty shots in this really quite brief outing from Tarr, and it took about 35 days to shoot. They are long and often trailing shots, but we cover very little ground — the ‘town’ nearby having been (we’re told) obliterated. This is a reducing, shrinking universe, and we never quite glimpse beyond the hill that frames the farm. Its single tree is a little Beckettian. Prosaically, it is reminiscent of Platonov’s Kotlovan; where a vast, sucking entropy undermines the workers’ efforts to build their radiant palace of the proletariat. Entropy reigns. Even here, however, Platonov ekes out a little slither of salvation — the alimentary dignity of patience. “Let the future be alien and empty, and let the past find peace in graves, in the cramped closeness of bodies that had once embraced, in the dust of love and forgotten bodies that had rotted together.”

— The horse, for Tarr, is a kind of canary in the coal mine. The same might be said for Bresson, whose donkey/mule/ass is really a kind of canvas against which humanity tells on itself. For Skolimowski, the donkey (or mule; Etc) is a “void” into which we pour ourselves, desperate for understanding — and this is why (it must be) he throws so much cinematic clobber at the poor creature. Drones, laser-shows, football lout bust-ups, incestual eroticism, grizzly parking-lot murders, red-soaked death metal dirges. All of humanity (in its accelerated, post-cinematic guise) is thrown at the void of Kounellis’ creatures.

— In each iteration, we — Buckaroo style — place more and more signification upon the horse/ass/mule (see how even the names proliferate). But might we want to be our best selves before them? Yes, and yet we cannot be. I am saying this: that Skolimowski’s Eo is to Bresson’s Balthazar what Gavin Brown’s Untitled (12 horses) is to Kounellis’s Twelve Live Horses (Untitled). See, different names? The horse is always (has always been; is always already) a surface onto which we project, and which swallows the projection — showing it for what we are, or pretend we are not, and at this moment in time, this moment in time in particular Leaving what? Fear, and beauty. Both. This is probably (pat, true) humanity itself. Neigh (by which I mean: yes).

If you liked this newsletter then please consider liking, sharing or subscribing. It’s lonely here.