EPILEPSY CRT CHANNEL HOPPING

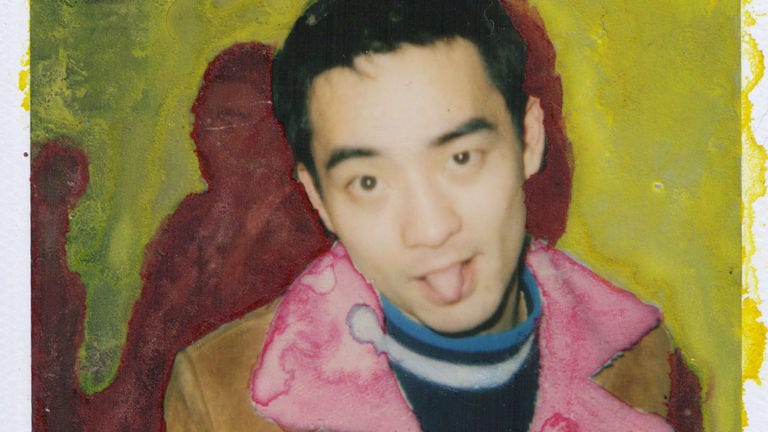

Stom Sogo — Ya Private Sky (2001), Silver Play (2002)

Just spent five days immersed in the program at LCMF. I had no time to really watch anything except that which was being shown. This was good because it meant that I had my first encounter with the work of Stom Sogo, who I’ve written about for this week’s (slightly delayed) newsletter. Enjoy. You can watch some of his work (in fragments, low-fidelity rips) here, here and here. With more than a cursory glance you’ll find more (and better).

— Things are obscure until they are not obscure. You can feel like you’ve seen everything already done, and then you see something new. It’s actually very refreshing. Premature death (by suicide). Before his death in 2012 (untimely), Stom Sogo was a projectionist at the Anthology Film Archives, New York. Behind the lens but not behind the lens. Years looking over the heads and shoulders of other people; other work. But his own work feels more than spectral, ghostlike. It has a corrugated physicality, a kind of poor-image transformed into a rich image.

— I say all this because, until a few nights ago, I’d never seen any of Sogo’s films. Context was this year’s edition of LCMF (the big sad), the films – two of them; – screened at intervals between pieces by the likes of Mariam Rezaei and Ben Patterson, Oliver Leith, etc. Fittingly, a kind of dirge of remixing. ‘Hysterical’. There was a fair amount of film spread across the five-day program, but this felt like the highlight; two films of quite uncompromising and unique vision, fun to watch, exciting to kind of dissect even while the various images (compressed, decayed, ecstatic) kind of spiralled away from me. It was good that the two films were also separated from each other; not shown back to back. I had a chance to stew.

— Born Osaka, 1975; moved to New York 1992; worked with Andrew Lampert, Raha Raissnia. Took, here, his interest in surfacing detritus and rephotography; by which is meant, either (a) filming the same location/scene twice (physically; a place) or (b) reshooting footage multiple times, and overlaying the results. Visa expired some time in 2004; returned to Osaka, but continued to distribute and share his films – via the internet, showing some at galleries, festivals, Etc. While I feel quite confident – on sure ground – about what was happening in the so-called postwar American avant garde in the 50s, 60s and 70s, I’m on less stable ground when it comes to the 1990s and 2000s. Sogo is a kind of course correction, a reminder that I should watch some more stuff. I’m ok with this.

— Films. Multilayered flicker films; not quite superimposition (which tends to privilege a kind of steadiness between the subcutaneous layer and the surface layer), but rather a kind of intermixing storm of images, making the experience (in, say, Ya Private Sky, 2001) like that of flipping between the channels of a CRT television (a television that’s on its last legs, basically all but broken but still coughing out images at a good clip). Electrified layers, which blur and bloom with all the sparkling, cloudy-edged chaos of a piece of fruit left in a glass of water (with a lamp shining, pulsing, through it; refracting). The experience is of shock and I think of a kind of torment, albeit a very joyous one (remember how Parajanov expressed that he wanted to ‘torment’ his viewers with his “artistic delight”?). Duncan Taylor puts it this way: “Sogo’s films operate on a kind of inhuman, raw impulse”, and I wonder about the unfittingness of inhumanity (as a label). They feel, if anything, profoundly human; in so far as we’re witnessing a hand (and eye) reach in to the surf/erratic detritus of the visual culture (ours) – found footage, TV clips, street scenes, all torn and ripped apart – and attempt to reassemble them into a new terrain. While it might feel like you’re watching some dodgy VHS tape that’s been recorded over a bunch of times (unintentionally), there’s clearly a very precise editorial eye at work here. It’s not robotic.

— Suffering from epileptic seizures. He (Sogo) said: “this is about the dreamlike images that I saw while having [the seizures]”. There’s a kind of parallel here with Brakhage and his attempt to recreate the naive imagistic world of childhood. He also remixed, repurposed. “If the old piece is not talking to the audience in this present time, it is better to make them fresh by cutting [...] almost every work I have made has its various versions”.

— Wrote last night (very late, quick scribble): “the distraction actually allows the film to wobble and then degrade, unexpected collisions, contradictions, coincidences emerge, somewhere between the intended and the unintended”. I remember saying (at the time; whispering) that it was like flipping through the channels on a TV very quickly.

— These two films must have been completed before he returned to Japan. Two years before he went back to Osaka. Really at the height of his involvement with the scenes in New York and San Francisco (where he was studying at the Art Institute). Spoke about his obsession with “stupid tricks”, by which he meant editorial techniques; interventions made into the film he’d shot or ripped (found footage), a play with projection, space, layers, depth. Bouncing, refracting. As early as 1997 he’d experimented (during a physical projection in SoHo) with bouncing the projection’s beam off liquid gels and disco balls. Andrew Lampert wrote: “the loops of film were spilling out onto the floor, gathering dirt, twisting up and slithering about like a snake”.

— The fruitful inaccuracies and lossyness of the MiniDV format. These two films typify the work he was doing with this kind of shaky, bloomy digital format. Footage culled from Japanese TV, video-diary elements, all of it degraded and deranged. There’s an exceptional moment of soft peace where we glimpse train lines (the electrical wires that hang above them; sky a kind of dark powder), black massifs of interrupting legacy artefacts, a kind of wobbling between tranquillity and noise. Sogo: “a movie’s reality should be as nasty and fucked up as possible”. Taylor observes that there are literally hundreds of Sogo’s tapes and video material “sitting at his former workplace and communal hangout”, the Anthology Film Archives, many of which are apparently in the process of being digitized. Seeing just two of these works at LCMF feels like the preamble to something deeper, and we might hopefully be on the cusp of a wider appreciation for his work.

— Back, slightly. Lot of dissembling. It’s difficult to contain any one element of his films, and to make them seem representative. The kind of abstract grandeur of TV when transformed into exploded loops. He plays with recursion, repetition; a celebrity chef of some stripe or another, head continually popping forward; dirge of voices (ad-style speak); TK. Silver Play (2001), things that seem like the tendrils of deep sea creatures, whirling; jagged stuttering (think La Jetee but sped up and blown apart); blurs of stretched light that willow and whorl across the frame; dizzying rhubarb pinks, mango yellows, lipstick purple, what is abstract (with a crushing belch of noise) materializes actually as a NY taxi; suddenly a moment of verite (man unwrapping sweet inside of taxi); TV ad, woman’s hand punches down to accent point in conversation (smiling) which coincides with sudden cut; faces zoomed in on TV set so closely that you can see the pearls and ribs of the monitor itself (e.g., it is drawing attention to the screened-projected format of projection itself). We are seeing seeing. You begin to wonder which scenes are drama, which news segments, which adverts. Logos and idents are (messily) kept in the mix. The same face, monochrome, the camera revolving around a loop as it settles again and again on his eyes.

— Ya Private Sky (2001) is much more deranged and disarrayed, closer to raw visual noise; strobing, erratic, arhythmic. Big globs of sudden, lossy light flicker wildly into your eye; they bend, stretch, alternate. This dirge-ditch of images almost eradicates the source material, and just as you think you’ve seen a thing (is that the bridge under a train track, is that a car, is that the edge of a hand, is that the interior of a restaurant - people eating) it is torn away, shrieking. Everything attains a kind of spreading stain quality; fatly round, bilious. The film’s end reaches a kind of high-pitched keening, where blobs of damp light look like photos of stars taken by massive interstellar arrays - a distant star looking like a bit of blurry jam spilt on a kitchen floor. These are soft at their edges and then cracked, fractured by legacy artefacts, the same thing (object) repeated in variations of decay. The privacy alluded to in the name seems to imply a kind of private seeing. It’s very intimate, really. This is dispersal.

— Aside. Slow Death (2000), completed a year before this duet, is a bit more restrained and bleak. Blown-apart/fragmented dispersals of black-white form(s) kind of stutter and fragment across the frame – shapes seeming to appear, dipping away, accumulating and departing; like a strobe pitched in molasses. Feels like a kind of recovery/engagement with early film, and attains this weirdly almost 3D effect as the focus of the frame clips around these emergent objects (all of it wreathed in this eerie cloud of damply shrieking noise). Disfigured faces, corners of mouths, outstretched arms and hands. There are zooms which alight on seemingly ‘irrelevant’ details, all of it quite pregnant with an anxious potentiality. Something is happening; the camera documents but doesn’t (directly, cleanly) reveal. Really exciting stuff honestly. Does it feel like rotoscoping? There is that. The illusion of three-dimensionality, as if the figures are moving against the flat plane of the screen. To come back to Andrew Lampert, they seem to “write’ and slip across the space where you’re watching them.

— I’ve just stepped on the edge of this stuff. More can be said, but first I need to watch a lot more – get a sense of its contours and terrain. Either way, it was a revelation to watch his films in that big cavernous hall, and he’s one of those filmmakers who, because of their obsession with the poor image, mean that you can just as happily get along with their work when watching it on a phone or laptop. But I’d love to see them on a proper CRT television, a box monitor. Hopefully a future event or retrospective might address that.

If you liked this newsletter then please consider liking, sharing or subscribing. It’s lonely here.

Great write up - I am really glad you were so struck by his work. It surprised and delighted me to see that his some of his films made it to a festival this year and I came across this today on Twitter. I have learned so much more about Stom in the year since writing that cursory glance of an article into a life lived to the limits. I have been researching his life much more deeply and hope to provide some more context and accessibility to his work. I can't say much more right now publicly but one thing I can say is that I have been working very closely with a longtime friend of his on a project for the last 6 months and to keep your eyes peeled :)