Cinema is an invention

. . . without any future.

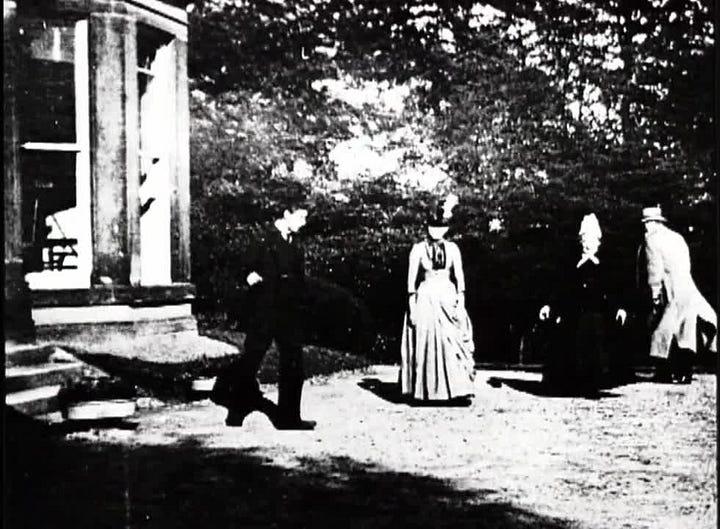

For the perambulators of Louis Le Prince’s Roundhay Garden Scene (1888)—whose 22 seconds are said to represent the first flickerings of film—almost nothing stands between them and the camera. Confronted with Roundhay’s fleeting duration, we watch them; and they—by association, and at many mediated removes—watch us.

Outwardly, the “scene” itself is quite straightforward. Four figures walk around a Yorkshire garden. It’s the middle of October; we can imagine the weather was warm enough; just before Summer tips into Autumn. There’s no sound, of course. In total—seeing as the film was shot at 7 frames per second—there are 154 frames. This explains its jumping-jilting; we’ve not quite attained the persistence of vision.

But something more complicated is happening than first meets the eye. For the woman on the left—who wears the pale pilings of late-Victorian dress—something unforeseen takes place: her view of Le Prince's camera apparatus is blocked when a man—hatless, wearing a dark suit—walks across her path, briefly obscuring her eye-line—and our view of her. It might be argued that this moment—only so many frames in duration—represents the first cinematic cut; severing not only our view of our putative subject, but the subject’s view of (an implied and putative) “us”. But just as the man obscures her body, he then reveals it again—joining his fellow strollers on the further side of the frame. He is walking very briskly.

In its earliest years, cinema anticipated much of everything that was to come; strobing toward its distracted-chattering audiences in scrappily un-theorized form. Films like these—which, in France, would become known as the “cinema of attractions”—had an uncanny way (at least, in retrospect) of auto-generating the entire history of film, making it a kind of immaculate conception: a technology that was wholly and already realized. It was only later—as Manny Farber reminds us—that film would crystalize and harden; the Hollywood studio system, and the notorious Hays Code, bringing programmatic order to the living skein of an early cinema in which anything and everything could happen. I’m simplifying things of course—a lot. I’ll go on: for the first-first avant-garde, we can glance further back than Ralph Steiner, Paul Strand, and Charles Sheeler; and a lot further back than Maya Deren (with apologies to them all). Rather, we can look at a garden in Yorkshire—and to the late summer of a cheerfully bourgeois afternoon. Film had arrived; and it had arrived fully-formed.

Maybe that’s not right; it might not matter. We could say, just as confidently, that the Lumière brothers, later—in documenting the egress of workers from their Lyon factory in 1895—had captured not only one of the earliest documentary motion pictures, but also one of the first acts of industrial surveillance. You wonder, watching it back, whether Louis Lumière took note of old Monsieur D’s pronounced limp, and speculated whether he was perhaps a little past it. Come what may, both Louis and Auguste were famously unsympathetic to the creative possibilities of the cinema they helped midwife; suggesting that film was only a trifling distraction—an “invention without any future”. In 1902, they abandoned the production of films, taking up—instead—the role of film-stock manufacturers. They were so wrong; but then again, maybe they were so right?

Let’s go back to the woman in her decorous Victorian dress. It might be Sarah Whitley or Harriet Hartley; the “stars” listed in Le Prince’s documentation of the film. In Joseph or Adolphe’s crossing of Sarah-Harriet’s eye-line, Le Prince had brought into motion—by accident or design we’ll never know—the yet un-theorized cut, and with it the first murmurings of the language-technique of montage that would, under the swiftsure eyes of Eisenstein, Pudovkin, and Kuleshov, bring into being the cinema as a jolting-jarring machine; a lathe which turns out new emotions; which shocks us into new alleyways of thought and emotion. Here, cinema doesn’t have “any future” simply by the fact of it having auto-generated its own future; making it immanent, already realized, and all-already there. At that moment, on the 14th October 1888, everything that film is or could come to be was brought into focus. But this isn’t really true.

The workers in Lyon occupy a strange historical place; as artisans and employees they were involved in the industrial production of cinematic machinery, but they also provided many of its first subjects. One of the most important early films is The Destruction of a Wall (1896) which, in its 89 seconds, shows a group of workers—Auguste Lumière among them, overseeing the work—as they go about demolishing a wall. I can’t say if old Monsieur D was among them. When the film was screened, projectionists were instructed—to the gasping delight of their audience—to advance and then rewind the film, bringing the litter and detritus of the wall back through a cloud of dust and returning it to its originally solid form. Film, in those early moments, was aware of itself as an instrument of mediation; a technology that was not just there to show us reality, but to rewire it. Here again, film takes leave of “any future”; after all, that “future” can be rewound—even if the actual wall has been carried away in sacks and wheelbarrows. But this isn’t really true; and the wall isn’t really film. Not by a long way.

I wonder about the Lumière’s much-quoted-but-also-not-quoted-enough appraisal of film; of an invention “without any future”. If they were really so gloomy about its artistic prospects, what led them to throw their weight—and their money—behind the production of film stock? There might be an element of snooty-nosed disdain here; in their deigning to produce stock in the same way an artisanal farmer might, shrugging, supply potatoes to McDonalds. Let them have their “attractions”; we will pocket their money. Yet, other filmmakers would—rubbing-hands—step into the breach opened by the perpetual demolition of the Lumière’s Lyon wall. Méliès, the Gaumont Film Company, Pathé Frères, yes, but later—and not much later—all the dark, kindling talents of German Expressionism. Pabst would come; Lang would come; Murnau would come, and then they would—variously—abscond to Hollywood, and into the clutches of that calcifying Studio System. The Lumière’s survived beyond the obliteration-moment of WW2, when the future showed what invention could, with violent abandon, really apply itself to.

If you liked this newsletter then please consider liking, sharing or subscribing. It’s lonely here.