Right, we can dispense with a longer précis on Pere Portabella — the underground Catalan filmmaker, parliamentarian and constitution-writer — because this essay isn’t necessarily “about” Portabella in the round; really, it’s about his expressive, textural use of high-contrast film stocks. It’s about his accumulated-exploding grain.

I’m looking specifically at those films he made in the first flush of his career, in 1968-70. I’m thinking about Portabella’s obliterating black-and-white and how it bootstraps certain ideas about what he was doing in those early years; a time when — in his own words — he was “conceiving the business of film from an ideological point of view”. Don’t let the “business” part of that off the hook; Portabella is an avant-gardist, but he has something to say about the machine-factory of “big” cinema; he takes aim at the ways we consume, spectate, and absorb films, particularly in the sclerotic post-war years of Francoist Spain.

Elsewhere, Portabella has cited Eisenstein (his 1923 “montage of attractions”) and Brecht (his alienation effect; we’re talking 1936). The montage of attractions operates through “aggressive moments” (Eisenstein’s words) that subject “the audience to emotional or psychological influence”, producing “shocks” that “provide the opportunity of perceiving the ideological aspect of what is being shown”. The aggressive-attraction-moment (or whatever you want to call it) draws attention to the film-as-film; it is a technical cat’s paw that shocks the audience into realizing what is playing, spooling out, before them. “I’m watching a film; but, what is a film exactly — and what is it saying to me?” For Brecht, it’s about the alienation effect: repel-repulsing the audience from the work that sits in front of them; inhibiting their identification with the artwork on a subconscious level. They are pushed away from it; they can’t sublimate or otherwise “reduce” the film through their conventional apparatus. Eistenstein forces you to feel something; Brecht forces you to sit back, repulsed; to analyze.

Through these early films — in the years 1968-1971 — Portabella took a collagist, metafictional approach to his filmic subject. In Nocturno 29 (1968), he gives us a surreal-dogmatic defenestration of the bourgeoisie, cue-cribbing from fellow countryman Luis Buñuel. In Cuadecuc, vampir (1970), he loitered around the set of Jesús Franco’s Count Dracula (1970), shooting allusive behind-the-scenes footage that squats over Franco’s film like an atmospheric fog. In Umbracle (1970), he’s giving us a bit of both; a suggestive portmanteau of reflections that blends documentary pieces to camera, dislocated Francoist cinema, and surreal scenes in which Christoper Lee (yes, that Christopher Lee) and Jeannine Mestre variously glare at each other, put jewelry on, remove their clothes, ride trains, walk around a zoological museum. Lee recites Poe’s The Raven; he stops, addresses the crew, and resumes.

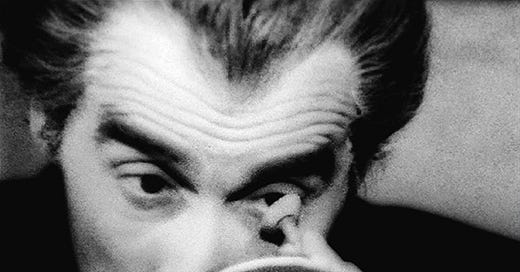

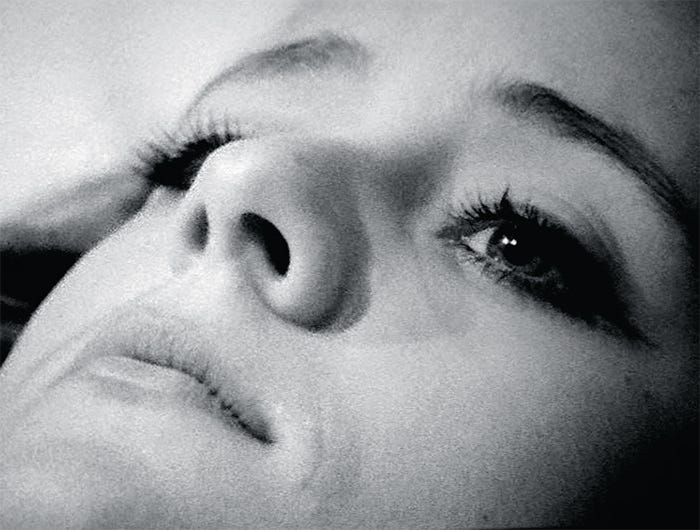

Throughout, Portabella makes use of a very characteristic film stock. It’s highly-saturated, high-contrast; whites are blown into an overexposed milk-froth of informationless pigment; blacks are exaggerated into a gothic intensity. There is a lot of information loss; the edges of bodies disappear against windows; depth is obliterated; eyes and hollows and pupils and folds of skin are flattened and scattered. The body — the subject — is exploded; made both precise and imprecise in ways that rub against the “naturalistic” grain of cinematic portraiture. There is a great deal of information loss.

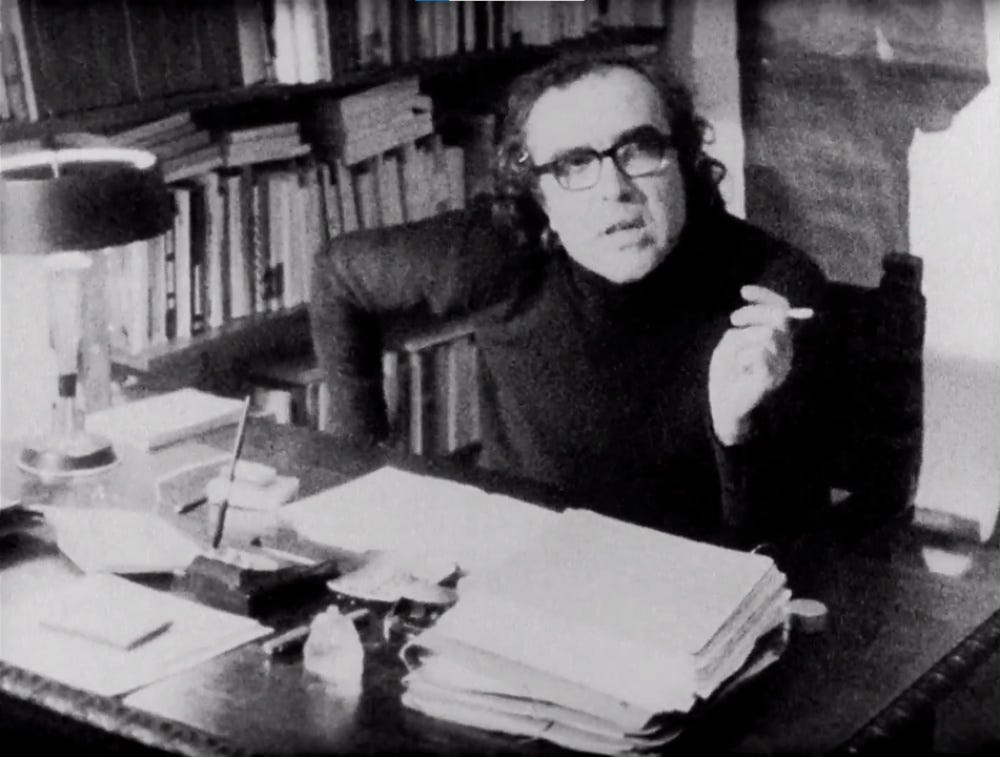

In Umbracle — in Catalan it means “worm’s tail”; it also refers to the unexposed film stock at the end of a reel — Portabella lingers, for ten or fifteen minutes, on pieces-to-camera offered by a trio of ciggie-smoking, turtle-necked intellectuals. They tell us about censorship in late Francosit Spain; they tell us about the ideological function of cinema. Portabella is laying his cards out; we’ve got no reason to believe that he’s satirizing these subjects. I think he is one of them. The first, reading from a typeset volume, lists a series of dictates to which all film productions in the country are subject. Rule 34 stipulates against depictions of violence; Rule 12 inveighs against those who would make light of the clergy. Portabella hard-cuts and repeats certain footage of Lee walking along a road (sunglassed, terse of mouth), climbing out of a car, spectating; a man is bundled (we presume by agents of the state) into a black car. It jump-cuts. Lee looks on, stiff-backed and recoiling. Elsewhere, Portabella luxuriates in showing us everything the rulebook says he is not allowed to: symbolized intercourse; nudity; violence; the death of animals. In one protracted sequence, he excerpts a shclocky Francoist puff-piece; a film about an army chaplain who, finding his pluck and courage among the bombs and bullets, fulfills his role as the padre of the soldiery. Its inclusion, here, is inherently satirical. Portabella gives us the violence he’s not “permitted” to depict; but this is Franco’s violence, the sanctioned blood-letting of the fascist state. The hypocrisy is rank; the film sequence is worse.

There are other themes he picks up, drops, resumes; there’s a woman answering a phone, bringing the receiver to her head and replacing it, again and again. This isn’t a cinematic loop (it’s not the film played back and forward), but rather a series of repeated actions; we can tell because each lifting-dropping of the receiver is slightly different. Earlier, we heard the unanswered ringing of a phone; Portabella interlaces these otherwise disparate segments; he’s producing a network of attractions that cut across the structure of his 84-minute film. They’re asynchronous, non-linear. Later, Lee stands on a stage and speaks to an unseen crew; his voice is at first lagged, his lips moving behind or ahead of his actual voice. Two clowns perform an extended skit; it’s about hypocrisy — and hats. Throughout, Portabella pummels the footage; it collapses, leaking its own data. Bodies come apart; flattening into silhouettes — a thicket of grain scrambles them further. Lee’s face is as sharp as a knife; as diffuse as smoke.

Portabella demonstrates that the image — the filmed image — is never quite “reality”; it flips a finger at Bazanian naturalism. Portabella draws attention to film’s materiality; the “worm’s tail” of its name — the tattered-scattered edge of the film stock itself. In Nocturno 29, an early scene shows a man or woman — it’s not clear which — drawing a spool of film reel across their face. Later, the image crackles and splits in two. Portabella reminds us that we’re watching a film; that film is necessarily a kind of mediation, an “intervention” (as he calls it). The “business” of film is the business of image-making; it is not about passively “documenting” reality. There’s also a man, entering a bar, who glimpses himself — in the bar — projected on a television. The voices and gestures of the people around him are slightly sped up. When Lee walks the Barcelona streets, Portabella intercuts footage from Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, Laurel and Hardy, producing a stark-dark and smiling meditation on the subversiveness of slapstick. “I’m having a laugh with you; I’m making a joke of this”. It is deadly serious.

Portabella’s first films were made during a period of intense censorship and repression. Erika Balsom suggests we can’t easily periodize his films. No, but we can identify certain techniques that apply to this very early phase; the smashed high-contrast era. Later, he’d shift into colour – and toward more naturalistic tones and lighting. There’s Warsaw Bridge (1990) and The Silence Before Bach (2007). Balsom talks of it as a cinema of “confrontation”, and this is borne out by Portabella’s own writing about his filmmaking; feeling the need “to intervene in a hostile, mediocre, grey, and repressive environment”. So we have “confrontation”, “intervention”. Portabella realises this through his use of blasted stocks, smeary grains — with nonlinear assemblages of allusive footage stitched together with little dialogue or expository structure. Their logic is associative (pace Eisenstein), and the ill-fittingness of the relationship between scenes (larking clowns; a man placing rings on a woman’s hand; a trio of monied men silently smoking in their club-house; taxidermied flamingoes in a zoological museum) sends us scrambling to identify the relationships between them. What is “real” and what is “un-real” (that is, staged) becomes unclear. With Cuadecuc, we can’t escape the allusion to Lee’s sometimes-seen Dracula as an allegorical horror-puppet of Franco himself; nor can we shake off the idea that Portabella is commenting on his own vampiric relationship to the film he is re-shooting. He takes aim at the state; he takes aim at film itself (and himself) — a kind of bloodsucking monstrosity. He is rending the garments of filmic illusion; it is an instrument — an ideological apparatus.

In 1992, Dirk Lauwaert — writing about Eric Rohmer’s A Tale of Winter — argued that a film has to be “ugly”. He alights on Rohmer’s bitterness toward the scenes and characters of that quite specular film. It’s not a world you want to share. He shoots the film in “a careless and haphazard manner”. The ugliness bootstraps Rohmer’s sense of irony toward his bored, listless characters; all of whom are mired in their own desperate lack of self-awareness. But it also helps us to “see” them as they are; to empathize with them. This doesn’t make it a boring film; the film is moving, intelligent, but “the images were made from the endless distance of the other side of the universe”. There’s a resonance with Portabella here; in terms of how he uglifies his shots — transforming flashes of wide Catalan landscape into blasted glops of black depth and itchy white. His characters, in moments of isolation or communion (in Nocturno 29, a man and a woman — both of whom are attractive — embrace on the stony soil), are rendered ugly. The lines and pits and scores of their faces are accentuated; their bodies are shredded apart. They are thrown away from us. Portabella wanted to anatomize the “hostile, mediocre, grey, and repressive environment” of late Francoist Spain; so, he gives us an ugly world — a “repressive” world. He shakes the image apart. The lens (his lens) becomes an instrument of brutalisation. Lee, in Cuadecuc, is made yet more terrifying and obscene than the character he portrays in Franco’s film. Portabella strips away the illusions of “nicety”; he darkens the mood and harshes the vibe.

Cinema can’t — and should not try — to merely document “reality”. Reality is a mug’s game. This is what Portabella teaches us; he wants us to interrogate the ideological apparatus of film; particularly his own cinema. Interruption is important; he doesn’t want us to “complete” a thought. In Umbracle, Lee’s narrative — his waltzing, speculative train journey, car ride, meander through a zoological museum — aren’t resolved. We’ve also got to remember how Portabella apes the interruptive idiom of contemporary life; there’s a scene — intercut here — where women try on shoes in a shop, with pumped-in lounge jazz. He uses similar music cues in Nocturno 29; a woman’s fractured silhouette through a glass partition. The “conventions of filmic representation” are, in Balsam’s figuration, totally scattered; we’re disoriented. If you start thinking, “ok, this film is about such-and-such” then you’ve already taken the bait. Portabella wags his finger; he winks. There are traps here; again, in Nocturno 29, he flips unexpectedly into colour – there’s a card game. It’s richly “symbolic”; the symbols don’t necessarily point anywhere. Later, a woman — again in colour — shops for fabrics in a busy department store; the seller unfolds a series of faded flags before her. Here’s yet another “symbol” that we would be foolish to read superficially. Instead, we should be asking why it’s suddenly in colour; Portabella is trying to coax-trick us into identifying with the film’s now “easy” symbology. We need to re-alienate ourselves; to step back.

Black-and-white; an obliterated mass of over- and under-exposed grain. This is where I began; kinda’ got pulled into thinking about Brecht and symbology. There’s another Portabellan trap for you. More than anything, Portabella is drawing attention to the ideological-industrial apparatus of film, and of how easily we can fall prey to its sub rosa machinations. In 2009, he spoke about the Franco years, asking: “what was the underlying factor that caused this understanding amongst us all to occur?” He’s talking about his (and his contemporaries’) rejection of Francoist dogma. But he’s also talking, obliquely, about the conditions that led people to normalize that same dogma. He’s asking a question; the answer is specular, and not easy to pin down. Simply “looking”, naturalistically — as a documentarian — cannot help us. Reality must be smashed; we must be repelled from the film that unspools in front of us. His hyper-saturated, over-exposed stock is part of that; a reflexive tool that quibbles and questions the dangerous material that film really is. Dangerous; but also liberatory. He says: tread carefully.

If you liked this newsletter then please consider liking, sharing or subscribing. It’s lonely here.

![Vampir-Cuadecuc/Umbracle [Blu-ray] – Severin Films Vampir-Cuadecuc/Umbracle [Blu-ray] – Severin Films](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!VjFK!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fc2e592ec-d011-42c2-9cab-0b069eb092e2_1080x810.jpeg)