Polish filmmaker Andrzej Zulawski was a creator of guttural, intense and hypnotic cinema; of something I’ve seen described as “necessary hysteria.” And it is an unapologetic kind of hysteria, something acknowledged, revelled-in - indulged. And I’ve been getting really hooked on it.

In 1975’s L’important c’est d’aimer, Klaus Kinski takes the lead in a play within a film; a bullish, brutal and chaotic interpretation of Richard III. It is too much; his face strained into garish, screaming chiaroscuro. Somebody back-flips onto stage in full Samurai armour and is dispatched with a kind of gestural, stabby flourish. It is entirely very cool! But also? Ah, too much. As I said. A reviewer in Le Figaro dismisses the play with pearl-clutching offishness; sending Kinski into a further theatrical strop; pummeling a passer-by whose only crime is to brush his hand against Kinski’s cloak. The only language is one of intensity, condensity. Live outrageously; be outraged. [screaming intensifies].

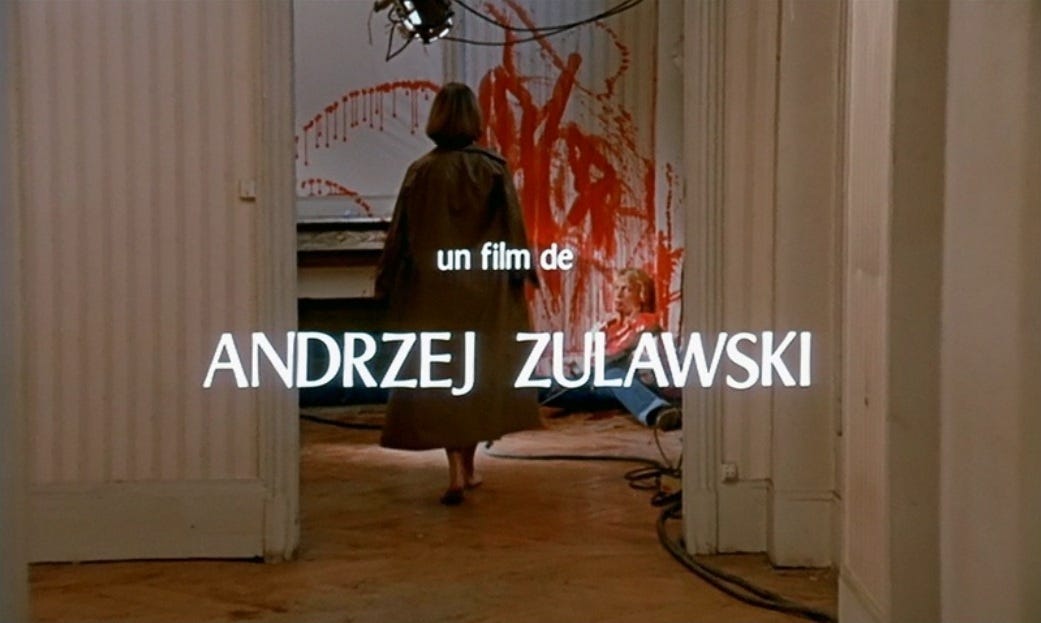

hey did Cy Twombly do the blood spatters?

Like Alexei German, Zulawski revels in the art of the closeup; lingering, pouring over, loving. But where German packed his actors — and bodies — within tight and compressed space, Zulawski sees his characters ricochet from the tight to the enlarged and cavernous. Romy Schneider, the film’s proper star, finds herself in a somewhat precarious financial position, yet rents a vast, and largely undecorated Parisian mansion; cooking instant coffee in a knocked-about tin pan while striding through towering, monumental rooms. Her bed is a mattress on the floor; a crumpled yellowing sheet. Servais Mont, the photographer who becomes obsessed with her, inhabits a series of interlocking and seemingly endless dark-rooms; again, sparsely furnished, stripped down to their barest; walls pasted with photos, slapped up there almost violently. An empty stage (decorated with only a coffin); a theatre whose seats have been covered with dust-sheets. Furniture — the world of material — is debased, denied, revoked.

Nah (says Zulawski, this is in his voice), no, we’re going to get really really close up to people; so you can see the luminous dark-wet gel of their eyes. The blood-crusted lip. The furrows; the dried make-up that accretes in the wrinkle beneath an eye. This is claustrophobia made yet more intense because the camera prowls around and leans into the actors within these very cavernous spaces. Back up. Go easy now. The proximity feels so much more intense because we feel the warp and slack of the space around us. We can retreat, walk back. But we’re not going to.

And this is entirely the thing - the reason I can’t find a suitable and appropriate scene from the film to share here, to demonstrate that; because the space around the actors is so fleeting, so quickly glanced at. Space slips away, is pushed back - but it’s there, caught in a second, out of a corner of your eye. That bigness shimmers and heaves in the background. We just can’t see it. No, we’re here; in the territory of the surface of the face; at the skin of the eye. The umbra between lens and light.