A shimmering lamentation on friendship and industrialisation

Dursu Uzala — Akira Kurosawa (1975)

Here’s a film for the soft middle days of February, and it’s one that I’ve subsequently described as my favourite Kurosawa. Who knows if I’ll hold that view in a year or more. I’ve always been a Ran man. But this is something special.

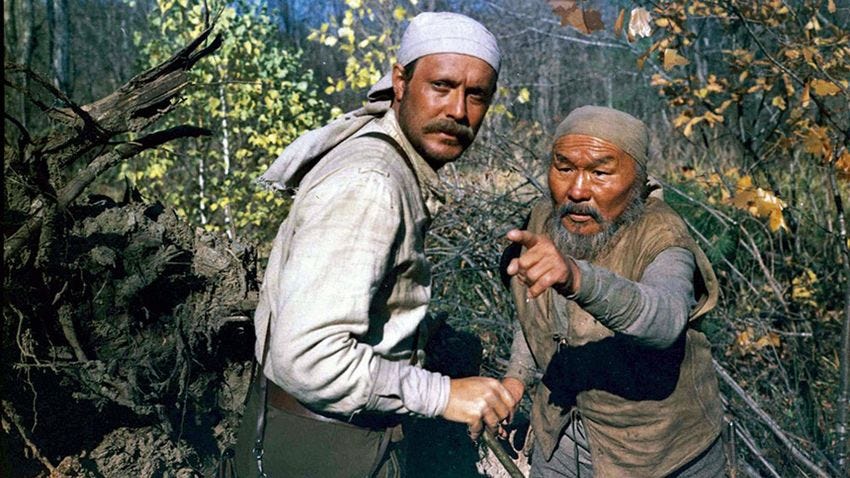

— Did you know that Kurosawa made a buddy movie? Dursu Uzala (1975) is a film in which friendship is allowed not only to exist in its layers of corrugated complexity, but to shimmer. Restrained. Cautious. It is both proximity and vastness. By this I am referring to the congenial warmth between Dursu (a hunter) and Arsenyev (an explorer and military officer), all of it leveraged by the enormous width of Kurosawa’s wide-mouthed lens. Each shot appears to stretch outwards, toward eternity. It provides scale (of man against the elements of nature). But it also comes to express the openness of their love and mutual respect. Gaping, its 70mm format (as good critics have made note) is not a thing of crushing alienation, but of intimacy and closeness.

— Restrained. Kurosawa knew about restraint. Rashomon is a film of restraint, paired back and boiled down. But his grand historical epics are the inverse; wild, boisterous, big. Dursu Uzala succeeds in being vast as well as restrained. These things are integrated. It is nature itself, the ecological breadth of Russia’s ‘far east’, in the wilderness west of Vladivostok. I was reminded of David Lean and his adaptation of Doctor Zhivago. But that is a book and film in which history penetrates and eventually overwhelms the space in which it unfolds. Individual lives are overwhelmed by it. Dursu Uzala does not cauterise itself from history. No. Dursu seems like the last member of an obliterated society, unable to adapt to the industrialisation that is turning the tundra into factories and towns. But the film itself does not sublimate itself to this historical structure. It exists out of time, even if that time is rapidly counting down.

— Kurosawa was not enjoying a good 1970s. His desire to work both internationally and in colour had been met with bureaucratic twists (his being fired from the production of Tora! Tora! Tora!) and commercial turns (the box-office flopping of Dodesukaden). Ejected from the hills of Hollywood, he found Mosfilm to have uncomplicatedly open arms. He was supplied with what I understand to be a supremely generous budget and the autonomy to adapt whatever work or story he so wished. Years before, he had dabbled with an attempt to translate Dursu Uzala for Japan’s snow-bound north, Hokkaido. It had fallen through.

— Within a landscape - characters. There is never a suggestion that Dursu and Arsenyev are at odds with one another. Their friendship is immediate, uncomplicated. Curiosity about Dursu’s cultural beliefs and personal eccentricities are never less than benign. These men - a column of slogging soldiers, backs bent with packs and surveying equipment and rifles - know that this is Dursu’s land. Optimistically, Kurosawa wipes away any sense of broader cross-cultural conflict.

— Difficulties. The Criterion Collection—care of Donald Richie—offer a jarring read, parotting a few teeth-grinding ethnographic tropes (like Dursu’s “native intelligence”, his embodying the “instinctive [people] of the Steppes”), while also stating that the film is shot continually at eye level. This simply isn’t true, at all! The actual film is a lot more sensitive than this (Richie is projecting), and far from glued to the level of the eye. Dursu walks and talks with his own sensitivities and eccentricities. Eyes down, and you’ll see an eye levitating far above the pink-sludge-grass of the steppe itself. Richie is right, of course, to pinpoint the gulf of difference between Kurosawa’s original and final script - the finished work being much lighter and less filled with despair than the former. With the writing of Dursu, it’s almost like Kurosawa discovered something hidden within the story’s twists and folds.

— This is not untrodden territory in Russian literature. Of aristocratic ensigns and hussars who embrace the rugged wilderness of the imperial frontier. Tolstoy’s Hadji Murat. His Cossacks. Pushkin with his Prisoner of the Caucasus and The Captain’s Daughter. These works fascinate themselves with the edges of empire, and of what men do there - of what they become. Blizzards, warm summer grasses. Swollen mountains and curvaceous sabres. The alternative? The sly salons of St. Petersburg. Propriety, prudence. The Russian ‘east’ (and its south, of course), became sites of an auto-ostracised imaginary in which poets and artists could - through physical trial, and ‘simple’ living - discover themselves.

— There, of course, lies a certain whiff of the orientalist imaginary, imprinting and projecting onto the other a mantle of ‘primitive’ authenticity. Kurosawa - in Russian eyes - was an outsider himself. And he is not blind to the film’s passive negation of Dursu and his lifeway. Arsenyev and his men mean well. But the wider structure of history will ultimately pulverise and eventually erase him. Olga Solovieva speaks of Dursu Uzala as a film of “mourning”. Its opening scene depicts (in 1910) Arsenyev’s return to the place of Dursu’s burial (we know him first only as an unseen body, a negated possibility that Kurosawa’s film will itself - temporarily - resuscitate). We discover that Dursu’s grave has been wiped off the map, the loggers who are constructing a village on its site unaware that a body was ever buried here. A village will sit on top of it. The trees that once marked the grave have “probably” been felled. The agitation of modernity-as-forgetting rears its head multiple times in the film, always softly. When - at the film’s finale - Arsenyev comes to identify Dursu’s body, he is greeted by an unsympathetic policeman who is keen to get on with “other work”. Dursu’s body is shrouded in a rough hessian sack. When Arsenyev lifts the cover, we do not glimpse the hunter’s face. His visage has been extruded. Forgetting is a transference into the realm of the un-visible.

— The eclipse of Dursu is the eclipse of the taiga, this vast and sublime landscape that is being swallowed by the sprawling industrialism of Russia’s expansion. Arsenyev himself embodies the tools of this erosion - his instruments of cartography subordinating the wilderness through the instruments of science and measurement. But only partially. The sublime escapes comprehension, logic, reason. It exists at the unfelt edge of sense. Notably, Arsenyev’s work occupies little of the film itself - the metrical tasks of cartographic measurement. It is not permitted to orient the fabula of the plot, nor the width of the screen (as wide as it is). Nor are beliefs of Dursu or the Nanai people subjected to lengthy explication. He invokes Amba, the god-animal of the tiger. He chastises the soldiers for their lumbering and incorrect behaviour in/through the landscape. But his knowledge is not footnoted, nor given a precis. It rises and disappears with his glances and words. We are witnessing only the edge of a vast structure of practises and beliefs. Kurosawa, instead, locates the film within the gravity of an unseen sensualism.

— Despite the quite literal imperial baggage that Arsenyev bears with him, he quickly assumes the ethical task dictated by Dursu’s gentle interventions in the landscape. They dismantle unsporting animal traps. They decline (at first) to fire upon a pursuing tiger (Dursu berates it, the soldiers check their shots). Dursu does not want money. It’s unclear why he agrees to assist Arsenyev and his soldiers with their job. A sense of overwhelming anomie, broiling loneliness. In one peculiar scene, the explorers discover the cabin of an old man who has escaped the torment of city living (his wife left him), spending some forty years high among the snows and firs of the taiga. He is without speech. Here’s a kind of mute mirror to Dusru and his patter about the landscape, a kind of lyrical cartography that does not so much subject the world to lexical order as reveal the ultimate incongruity between sense and landscape. Words are always imperfect, imprecise.

— Dursu’s time is speeding up. He approaches death. In Kurosawa’s original script, the hunter would have a traumatic vision of his own demise, a horrified and ecstatic vision crawling from the space of dreams. In the later script, the events are more prosaic. Dursu’s sight is failing him. He doesn’t know his age (we presume sixty or seventy, his hair growing increasingly grey). The hunter can no longer fire his weapon. Dersu attributes this to a second encounter with the tiger that goes awry, wounding the creature in a seeming effort to save Arsenyev. Fear overwhelms him. His irritability accelerates. Kurosawa begins to manipulate light and colour, flowing murky stabs of red light and bokeh into the wobbling and iridescent frame.

— We share his blindness, the ocular disorder. Late in the film, Dursu agrees to live with Arsenyev in the city. It is here that he becomes most despondent, the vast 70mm width collapsing to a “box” (as Dursu himself calls this space). Here he is like Asenyev in the wilderness, without map or understanding. The world of the city is incomprehensible. Knowing the proximity of his own death, he decides to depart. Arsenyev offers him the gift of an expensive modern rifle. When the policemen discover Dursu’s body, they reflect that he must have been killed by a thief who fancied this icily technical weapon. The metaphor eats itself. We’re declined the vast maw of the landscape at this juncture, replaced instead by the closing claustrophobia of dark woodland and tight houses. I think this feels like the ambient dread that licks the edges of Ivan Bunin’s Dark Avenues (1946). “And closing his eyes, he shook his head”.

— Colour. It is a function of the seasons. It turns to grain and bloom at the camera’s behest. Summer is a cracked yolk of fizzing champagne. Spring is licks of vibrating green that surge out from great tangles of brown and grey. Winter is not white so much as red and blushed pink and obliterated blue. Kurosawa was both subtle and unsubtle with his colour, but never predictably so. Just look at this, below! Here’s winter as Nikolai Galakov or Levitan. The width of the Russian eye transmuting the natural world into the skin of a pearl. Winter is not white.

— The abutment of melancholy and mourning. Dursu Uzala is a process of collapsing and tightening, much like a lens’s aperture that folds beetle-like into its own carapace - shutting out the light. Dursu has saved Arsenyev’s life many times. Dursu has compensated for Arsenyev’s distress and disorder (as brave as these things themselves are). Lost at the edge of a vast, frozen lake, both Dursu and Arsenyev are picked out like ants against a vast, howling plain. This is the gigantism of nature at its rawest - something so vast and indecipherable that it swallows even Dursu too. His ingenuity is sufficient to save them, but only just. Kurosawa reminds us that Dursu himself is ‘just’ a man, and that even he is merely an interpreter of the natural world, not its master.

If you liked this newsletter then please consider liking, sharing or subscribing. It’s lonely here.