I ate a lot of baklava this weekend, and watched a mess of films (shout out to Bogdanovich’s Paper Moon). This is why I’m late with this newsletter, but who’s keeping track?

― The ecstatic daubs and scratches of Brakhage. The melodious, expanded superimposition of Mekas. The arrhythmic flickering of Peter Kubelka. From Colorado and New York to Vienna, the annals of the post-war avant garde offer up an index of formalistic experiments whose stated aim (however diaphanous) was to interrogate the act of seeing itself. Takahiko Iimura (Japanese, born in 1937) is not frequently figured within these formations. His practice has always seemed - at first glance - peripheral; adjacent to the well-documented kultur of experimental filmmaking in the American and European traditions. He appears like a silo, complimentary yet displaced. But the points of ingress and interaction between them are many and sustained.

― The early film poems comprise a selection of works completed by Iimura during the earliest phases of his filmmaking career (this excludes the ‘60’s experiments’ of 1962-64 as well as some other related/unrelated works, including Onan, Rose Coloured Dance, and AI/Love, Etc). He arrived in New York in 1966, at which point his self-stated absorption of the American avant garde really took off. He cites the Neo-Dada experiments of hole-punched stock, erasure, painted-on celluloid, and formalistic experiments in editing and superimposition, and how all of these things came to influence his making. You can get a really good sense of this from The Collected Writings of Takahiko Iimura. It’s very good.

― Throughout, he was searching to explore “new areas in film expression”. And what these films share with the American avant garde is a sensing toward disorientation and disfiguration, and an embracing of curious (un)worldly forms. Generalising statement: the subject was not simply the world, but the interrogation of the world through the equipment and technologies afforded to the filmmaker through film itself. It is an obliteration of ordinary sense through tools that must themselves be ‘mishandled’ or pushed to extremity. Raw film stock becomes a canvas (scratched on, exposed, dismantled, repurposed). Behaviours and actions - as well as the bodies that perform them - are disintegrated and reassembled. It is this liberation of film from narrative that seems to have attracted Iimura in these early years - the same experiments that the likes of Brakhage, Frampton, and Markopoulos (et al) were pursuing across the Pacific. Really he is in dialogue with them. His work straddled the emergence of the structural film from the imagist filmmaking that had preceded it.

― In Dada ‘62, he shoots the work of other physical artists - of plaster masks and billeous constructions. Film, here, is an expressive tool for documenting the perception of art itself. Broadly, these are works of motion - handheld and freewheeling. They pounce and leap through near unrecognisable fragments of objects and spaces. In I Saw the Shadow (1966), the discoloured camera captures the shadow of a person (Iimura himself) walking across a pavement. Between the fatiguing of the stock and the vibrating motion of the lens, its subject (leg[s], tiles, shadows) becomes utterly disoriented, unclear whether it is the camera or Iimura’s shadow that leads the procession. A world transformed (nodding to Shklovsky here, defaniliarised). The barrier between lens and filmmaker is collapsed. You can almost feel the delicate/heavy weight of the camera at his side, in his hands.

― Throughout his films, he has always been interested in subjecting forms of dialogue (be it seeing, speaking, or listening) to processes of deformation and inquiry. Even a partial list of his in-distribution works is towering in its diversity and quantity. But it’s also apparent where he was in dialogue with the wider avant garde. Not only collaborating with the likes of Yoko Ono and John Cage (luminaries both!), but explicitly referencing DADA and Fluxus in his titles and thematics.

― These particular works, however, were completed between 1962 and 1972.. Early. As Iimura himself explains, “film poem is a term used in the 1960[s] for experimental film, borrowing from literature [...] it means non-narrative and short form. Also it often meant lyrical as well, though not necessarily so”. A more academic precis (less good) speaks to Iimura’s career-long efforts to ‘radically explore’ the “signifying systems of meaning in moving image making”. Meaning here is elliptical. By invoking poetry, Iimura draws upon all kinds of textual and semiotic structures which we feel our way through when encountering his films. The rhythms of repetitions, cuts and montage as line breaks and punctuation. Perhaps it is their metaphorical quality, gesturing toward a thing that is not the thing-itself. They are brief. From 3 - 4 minutes to 20. And while they are not entirely silent, their sound is non-diegetic. For Dada ‘62, it is a dull clicking and interspersed clacking, something like the blurred fumbling of Mekas’ Walden - those sounds picked up during his handling of the equipment he used to record. An intrusion of the technology of the film into the world is exposes and explores.

― It’s not immediately clear how the early film poems differ from other contemporaneous projects Iimura was pursuing over the same decade. Some of these (other works) seem to lean a little more closely to singular themes and experiments. But the line is slippery. The best definition of the early film poems are that they are six films arranged together by Iimura under the title early film poems.

― Masks and busts. Protrusions of legs and arms (and the shadows they cast). Shadows are multifarious and constant. In these films, the human body is rarely if ever glimpsed - the shadow favoured in its place. Broadly, these films are imagist - depicting the world of the concrete, the sensorial, albeit subject to the processing/disfiguring machinery of the camera. I like that you can really feel the weight of Iimura’s camera in his hands, reading-back the gestural movements and improvisatory choreography of his filming body - a human(e) extension of the camera as equipment.

― Elsewhere. The documenting of exhibitions and other arts (DADA ‘62, Etc). Here there is a similarity to the ‘action’ films of Viennese filmmaker Kurt Kren, whose shooting of the action performances of Vienna Actionism during the 1960s would become influential avant garde films in their own right. Here is a filmmaker who started by ‘documenting’ (albeit idiosyncratically), and turned eventually to their own structural projects.

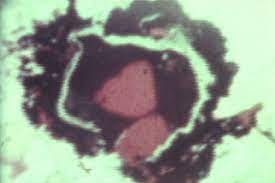

― It is with Iro (1962) - meaning ‘colours’ - that Iimura most completely disfigures the world. Diaphanous, wobbling water and pooling paint. Light, shape, and colour vibrate and throb. Here is a movement toward total abstraction, its images coalescing with the vibrant largeness of nebulae. With The Pacific Ocean (1971), Iimura - now well embedded in the US - uses the ocean as his canvas. Light leaks, highly exposed frames, bokeh and movement. Later, in 2010, it was set to a repetitive and fading in/fading out piano performance by Akiko Samukawa. The experience (accentuated by the piano) is both inquisitive and disorienting; the ocean’s ruffled, light-soaked surface crawling with its own mesmeric energy. It is like an explosion, or the surface of a strange, unforgiving planet that is not our own. With it, Iimura seems to have anticipated the seething, glittering vibrance of Tarkovsky’s alien planet in Solaris. But time speeds up, and the disorientation increases and expands (the lens, becoming of the sea itself). Visual artefacts of the camera (leaks, tears, eruptions) are part and parcel of the making, as are the many accumulated elements of decay that have built up on the film stock over the years. I don’t find myself really begging for a restoration, enjoying instead the emergent deformation that these things entail. The softness and diffusion feels very much part of the overall effect.

― For Iimura, the face (as an expressive vehicle to be subjected to experimental intervention) would not become a meaningful subject until the late 1960s at the earliest. These are probably the most commonly occurring images of Iimura’s work online (the big, stretched portrait of Performance: A I U O NN SIX [1994]). You know it already. But faces are not at all a preoccupation for the early film poems. It is rather the material world (organic or man-made) to which he turns his attention. Among the early film poems, it is Honey Moon that emerges as his most intimate and personal work - a documenting of his new marriage with Akiko Iimura. Like Mekas, we’re offered loose, handheld (and tumbling) examinations of the social and material world (here, temples, trees, streets, spaces). A quick pace of editing and and often frantically flickering montage embody the rhythms of the actual human eye (as with its repetitive zooms). I assume that it’s Akiko’s body we glimpse here and there, be it her shoulders, the back of her head, or her feet stepping across pavements.

― But again, all of this broadly reasserts Iimura’s interest (first and foremost) in film as technique and technology. In his own words: “I am concerned with the whole system of video, not just what you see on the screen, but including the camera, the monitor, the whole system”. This would anticipate his increasing structuralism in the 1970s and 80s, where repetitive experiments came to absorb his creative energies and outputs.

― For Mekas, writing in 1990, Iimura maintained an “enigmatic, mysterious presence”, while remarking on his conceptualism and minimalism. And there is much in films like Kiri (The Fog, 1970) which really sing to this ethereality. Shot on 8mm on a mountainside in Japan, much of the frame is filled with a disorienting, abstract mist. One of the many DVD blurbs for this work suggest ambiguously whether Iimura did or did not scratch or graze the stock on which it was shot (“we almost believe it to have grazed the filmstrip”). Either way, through intentioned intervention or time’s decay, a dynamic conflict emerges between the billowing white of the film and the particles and specks that litter the frame. Here and there, the branches of a tree emerge into view before fading moodily away. It is silent. You can imagine the sound for yourself.

― I want to come back to the idea of the film poem/film as poem. If a poem is a kind of disfigurement of language against sense (an intervention in the communicative surface of ‘ordinary’ text), then the film poem occupies a similar space. They have line breaks, rhythms, erasures and tensions. They’re also frequently, metaphorically, about form - as well as an interrogation of writing-from itself. Iimura is really always the subject of these films (i.e., his eye and body and their relationship to the camera and its lens). I also don’t want to read too much into it. For Iimura, these films are atmospheres - visual metaphors leveraged from the thirsty eye of the camera. And like all (good) poems, they reach excitingly toward the defamiliar.

If you liked this newsletter then please consider liking, sharing or subscribing. It’s lonely here.